Brujas: Radical Skate Style

Skate crew, clothing label or radical activists? Good Trouble talks to Arianna Maya Gil, co-founder of Brujas, about authenticity and the power of aestheticized politics.

Founded and developed in New York City, Brujas has created a strategy for how to spread radical socio-political ideas through the framework of a streetwear and skateboard apparel company. Co-founder Arianna Maya Gil, who grew up on Avenue C in the Lower East Side before her family moved to Washington Heights while she was in High School, was very influenced by both skate culture in the L.E.S. and radical activists she met throughout her life in the neighborhood. Once her family moved Uptown, she had to integrate herself into a new skate community in Uptown New York, which is when Brujas began.

Gil says she is not sure whether Brujas started “as a a party, or as a skate crew, or as a skate friendship–two people who threw a party called the same thing: ‘Brujas Parri.’” Gil stresses that they had no background in business or branding, and when they started using the name: “I didn’t really know anything about how [branding] works so I was just like, ‘she’s Brujas, that’s brujas, that tree is brujas.’ Because, that’s mad natural and organic to be like– if you embody the energy that I want more of and I’m out here promoting something then I’m just down to promote whatever you’re about and elevate your voice and maximize the potential of your ideas.” Gil credits her god sister, Robin Giordani, with branding the concept by creating their internationally recognized logo, which Gil sees as essential to their commercial success: “it’s the dopest logo. Every, every, time we put it on something people buy it. It’s crazy.” A friend, Rafa, was the one to first print the logo on a hoodie. “I come up with good ideas to like creative direct but like its just crazy so many people came to influence the course this shit took.” Although creating the successful business Brujas is today may not have been entirely intentional, it was directed by an authentic message and desire to support people who think like them.

Co-founder Arianna Maya Gil

“Brujas had effectively leveraged the growing commercial popularity of streetwear and skateboarding fashion to make a direct political impact and spread a radical idea–prison abolition.”

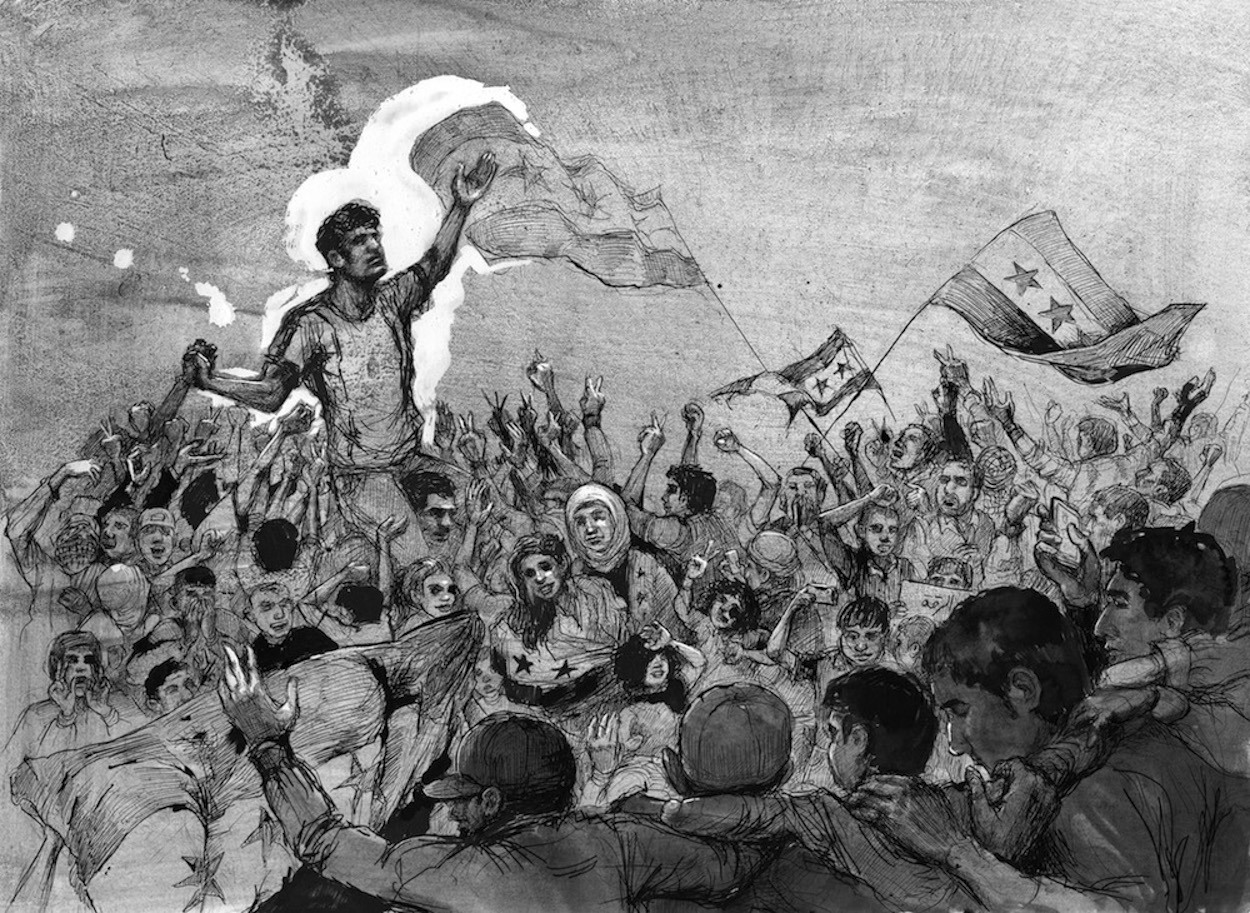

A Brujas’ pop-up, fundraising event

Now that the ten-person collective has developed a system that uses Instagram, parties, protest, and skateboarding to sell clothes and spread a message, the group has become more structured. This started with their first drop of apparel, a prison abolition fundraiser named 1971 after the date of the Attica prison riot. They raised money on Kickstarter which they used to print clothes (that they sold to increase the fund), send to people in jail, pay fines, and donate to prison solidarity groups. Brujas had effectively leveraged the growing commercial popularity of streetwear and skateboarding fashion to make a direct political impact and spread a radical idea–prison abolition. Gil says their continued use of this formula is an intentional strategy to spread their ideology. “Using a business and merchandising strategy [uses] the system against itself because using merchandising and commodities is how everyone in this world has accumulated power. We have to use that same structure to accumulate the power to proliferate the ideas and have the right people pay attention to those ideas… and most people are interested… in paying attention to people who have commercial power and that’s just the reality. Styling and aestheticizing politics is just strategy, you know? And it’s fun and it’s more accessible.”

Co-founder Arianna Maya Gil

But Gil, who saw how the viral popularity of Brujas in 2016 lead to an explosion of commercial support for women’s skateboarding and the use of aestheticized politics as a marketing tool, is disgusted by the inauthentic co-option of this strategy. While Brujas uses commercial popularity as a tool to change the material conditions for marginalized groups, corporations who have adopted the strategy do not. “It’s really wrong. [To] take a subculture and you just use it to sell things that doesn’t benefit the community… [Urban Outfitters] made like 500 million on a campaign using female skateboarders. That’s fucked up.”

Although it is disturbing to see their successful strategy employed superficially, Gil is still excited that as a result so many more women and femmes have started skateboarding. To her, this fundamentally makes skateparks safer for girls. “If there’s more women in spaces, there’s going to be more witnesses, [and] more women aren’t going to be alone. If you’re the only girl at a party and half of the boys in the room don’t say ‘hi’ to you because that just happens, they don’t acknowledge you, and something fucked up happens to her, and nobody acknowledged her presence in the first place, then there’s less witnesses and less accountability in the space. Real ass violent shit happens to women in public spaces and so if it’s possible to, like, create more women in public space, then more women will be safe in that public space.”

“Of course there has been a legacy to this work as there has been a legacy to every single kind of activism. People can say… that it was bound to happen. You know calculus was invented at the same time in two different places. I love that story. A truth is going to surface.”

The inauthentic co-option of their brand and those critical of Brujas’ claims to fame–making women’s skateboarding and aestheticized politics as marketing the mega-trends they are today–do not discourage Gil. “Of course there has been a legacy to this work as there has been a legacy to every single kind of activism. People can say… that it was bound to happen. You know calculus was invented at the same time in two different places. I love that story. A truth is going to surface.” Brujas continues to produce writing, political action, a clothing line, and unique parties. Their next season will focus on uncompensated labor and difficulties doing business as a woman and as a collective.

Words by Esther Loup Hershkovits / Photography by Orlando Gil

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.