Louder Than Bombs: the Art of Peter Kennard

Talking Stormzy, Kate Tempest, Jeremy Corbyn and 50 years of incendiary protest art with PETER KENNARD, the greatest political artist of his generation

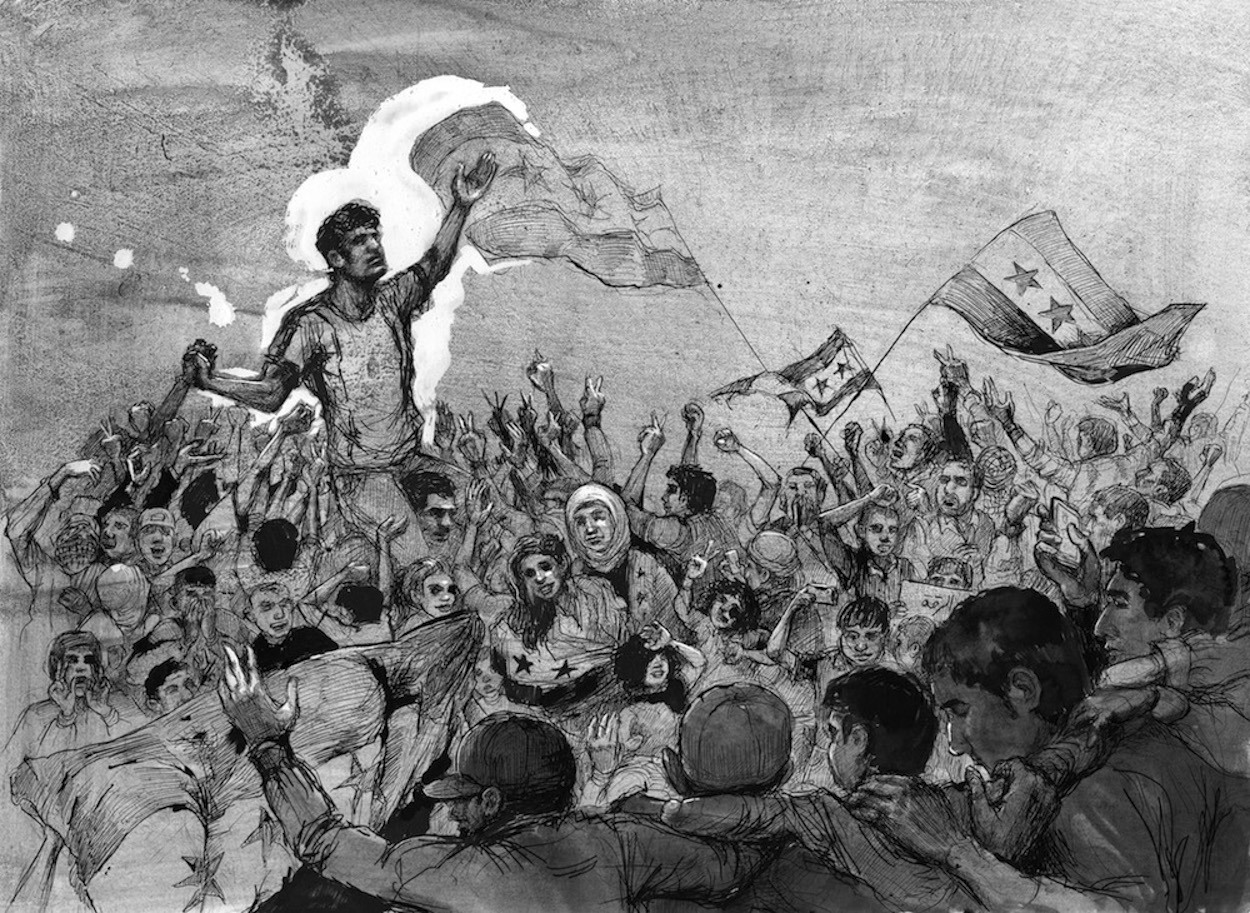

PETER KENNARD has been called the greatest political artist of his generation. If you weren’t familiar with his name, you’ve almost certainly seen his work – whether it was his iconic photomontage work for CND in the 80s, his juxtaposition of American cruise missiles into John Constable’s Haywain painting, or a horrific, grinning Tony Blair taking a selfie in front of a burning oil well in Iraq (part of his practice as kennardphillipps, a collaboration with artist Cat Phillipps). He has been making incendiary work for almost 50 years and shows no sign of slowing, with a flurry of activity around the UK election earlier this year, as well as his signature stark, black-and-white cut-ups appearing on the Kate Tempest album cover and in her tour visuals.

Protect and Survive, 1981

HARRIS ELLIOTT is the British creative director and visual storyteller who made the connection between Kennard and Tempest. He was also co-founder of touring exhibition Return of the Rudeboy, a celebration of the ‘attitude and spirit’ of West Indian-British street style, and has styled Pharrell and Dizzee Rascal, as well as the touring incarnation of Gorillaz. GOOD TROUBLE brought Kennard and Elliott together a few days after the tumultuous conclusion of the June UK election, in which British prime minister Theresa May won, but found herself weakened and humbled by a surprisingly strong showing from opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn, riding the wave of a youth vote surge most mainstream commentators had ignored or failed to notice. (This interview is extracted from the limited-edition print publication Good Trouble Issue 23, which is available now.)

Broken Missile, 1980

GOOD TROUBLE / HARRIS ELLIOTT: Peter, how did we start working together?

PETER KENNARD: At an exhibition on Stanley Kubrick at Somerset House in London. I had made an installation on Dr Strangelove, called ‘Trident: A Strange Love’ for the exhibition. Harris was already working as art director on Kate Tempest’s album Let Them Eat Chaos (top image) and he thought my photomontages might work well with Kate’s words. I felt an immediate connection to Harris’s way of thinking and we got on like a house on fire. It was terrific working with someone who was so committed both to the poetry and the montages, and could aesthetically and politically put them together to create the strongest possible blast at the order of things.

What do you make of the mood this last week in the UK, throughout the elections? It’s been wild...

It has been amazing in the UK since the election, it feels like a dam has broken. I can’t remember a time in the UK when the whole establishment, politicians, pundits and corporate bosses have all had such a shock to their belief systems. Suddenly, people have voted against the grain, for a socialist politician and a manifesto that really wants to attack the increasing poverty at one end of the scale, andincreasing wealth at the other. A politician has never been under such a constant barrage of lies and character assassination in the UK as Jeremy Corbyn has during the campaign, but be has held fast to his principles, not compromised his beliefs and won the confidence of millions of people – in the same way as Bernie Sanders in the USA.

“It is possible for contemporary culture to be an integral part of the worldwide movement for change – ‘For the many, not the few’.”

What has the role of the youth been, and what inspires you about that? Things like Grime for Corbyn and crowds of young people getting excited and involved…

It feels to me that the anger young people feel is switching them on to getting politically involved, from support for Corbyn and Sanders to campaigning for legislation on global warming, fighting racism and joining together to demonstrate against the obscenity called Trump. In the UK, grime star Stormzy among others has been campaigning for young people to register and vote. In the final hours of the election campaign, he told his Twitter followers: ‘Please please vote. It’s mad quick. Just go and do it. I used to think nah fuck it it’s long what’s my one lil vote gonna do’.

Haywain with Cruise Missiles, 1980

What was it like working on the Kate Tempest artwork?

It was a fuckin’ marvellous gig for me, because I was working with a great art director on material written by a woman whose work puts into poetry the passion for a better world that I attempt to put into my images. As Brecht said, culture should ‘not look at the good old days, but the bad new ones’. By imaginatively confronting the truths of inequality and inhumanity, rather than some imagined utopia at the end of the rainbow, it is possible for contemporary culture to be an integral part of the worldwide movement for change – “For the many, not the few”.

Inner artwork for Kate Tempest's Let Them Eat Chaos

What were a few key moments in your career that made you committed to what you were doing and why?

I was studying painting at Slade School of Art in London in 1968 and went on demonstrations in London against the Vietnam War. At the same time, the workers and students were out on the streets in Paris and Soviet tanks were rumbling into Prague – there was enormous social and political unrest across the world, and I wanted to make art about it. I wanted to find a form that could not just be shown in art galleries but could become part of people’s everyday experience on the street and in public spaces. Painting seemed to me to be too weighed down with art history, so I started using photography. A photograph is a trace of reality, so I could cut, tear, stamp or bleed on a photo… and however much it was worked on, it still took one back to that original trace of an actual event. Then, through making photomontages I could join images of the powerless and the powerful, the oppressed and the oppressor, to make critical images that could be turned into posters, badges, placards, radical magazines, and also be used by campaigning groups and NGOs and so on.

What are a few things that give you topical or visual inspiration?

I read the news, go on demos, talk with activists and look through hundreds of photos, as well as take my own for specific projects. The topics choose me, I don’t choose them. Very occasionally, a commission comes along that ties in totally with my feeling about the world, as was the case with the commission from Harris with Kate’s work. That became an inspiring three-way collaboration, which branched out into making moving image work, which was projected at some of Kate’s live performances.

“Trump is the apotheosis of the business world taking control of the reins of political power. We need to find art-forms that can be allied with the enormous protest movements that have been formed since he came to power.”

After many years working in collage and changing imagery to create messages, what insights has that given you into this new era of ‘fake news’ and social media lies?

I feel more intense about making alternative images than ever. Fake news that tries to brainwash the voice of the people is so prevalent, both in the established print media and online, that it is now up to the dissenters, the leftfield thinkers, activists to find new ways to get to the truth of what is going down across planet earth – or else, we all go down. Climate change allows for no let-up in our struggle to find ways to communicate through the corporate fog. It’s the same as it was, but more so and neoliberalism is breaking down – the inhumanities of the free market are attacking all but the 1%. There is a state of emergency that is not answered by our governments selling arms to barbaric regimes like the Saudis, but can only be answered by citizens finding every way possible to change the status quo.

The Kissinger Mind, 1979

You’ve depicted figures from Thatcher to Kissinger… What do you make of Donald Trump in comparison?

Trump is the apotheosis of the business world taking control of the reins of political power. We need to find artforms that can be allied with the enormous protest movements that have been formed since he came to power. It’s happening already, even MOMA rehung a gallery to show their revulsion at the Muslim ban.

What has been your relationship with the art world over the years? And the Imperial War Museum?

I’ve always believed it’s really important to show work in every context possible, from the museum to the street. Public galleries are vital forums for showing art to people who may not have had an opportunity to spend some time with art. Doing workshops with visitors to public galleries is also a vital means to reconnect people to their innate creativity. More and more, art in itself is deeply important as a means for people to express their humanity. In many countries, artists and writers are locked up for expressing the horror of the regimes they live under. The blue chip art scene is just the icing on the cake for the billionaire investors – the importance of the actual world of art and artists lies elsewhere. The Imperial War Museum has supported anti-war artists for many years. For me it was a great place to show anti-war work that I have been making for nearly 50 years. I worked with a brilliant curator, Richard Slocombe, whose inspired curation of my exhibition allowed visitors to see my work in every form – from gallery-based photo-paintings, to images printed on leaflets, t-shirts and badges.

Egg Timer

Ultimately, what role can art and creativity play in bringing about social change?

I believe that art in itself does not change the world, but allied with protest groups, pressure groups, NGOs, anti-war groups and so on, it can create images that lodge in people’s minds and encourage them to take action, and become involved socially in change. I have had emails and letters from people over the years which say that after seeing my images that they were encouraged to join a disarmament group, Amnesty, Greenpeace and so forth.

You collaborate with different artists from Banksy to Cat Phillips, how does that affect the way that you work?

Collaboration has always been really important to me. I’ve worked with writers, artists, designers and filmmakers. It’s great to break down the romantic idea of the lone artist in their studio waiting for divine inspiration. Through collaboration, new thought can emerge that is more than the sum of its parts. Since 2002, I’ve made a lot of work in collaboration with another artist, Cat Phillipps, we work under the name kennardphillipps. We originally started working together to express our horror at the invasion of Iraq, often using photographs that never got published in the press, as they were too horrific for the whitewash that was being propagated in the aftermath of the invasion. Since then, we have worked on many issues, especially since 2008 trying to rip off the veil that covers the obscene profits of the banks, bailed out for our austerity.

You have been dubbed Britain’s most important political artist, I’m assuming you don’t care about titles, but does this put pressure on you, or is that irrelevant because of your message?

I’ve been around making political work for a long time and seem to keep going, so I reckon longevity is the reason why I’ve been called that. I’m under no pressure to produce anything I don’t believe in, The only drag is getting older, as there is more visual protest needed now than ever.

““If you work on a campaign to sell baked beans, you’ll know in a couple of months if more cans have been sold... But with art, it could take generations of activism and protest to get any change, and even then it can’t be measured.””

In what ways have you seen your work affect social or political change in terms of mindsets?

The thing is, if you make political work, you’re in for the long haul and its effect can’t be measured. If you’re in advertising and you work on a campaign to sell baked beans, you’ll know in a couple of months if more cans have been sold and you can measure your success. But with art, it could take generations of activism and protest connected with the art to get any change and even then it can’t be measured. John Berger wrote, ‘The strange thing about art is sometimes it can show that what people have in common is more urgent than what differentiates them’. If I’ve done that, then it’s enough.

Newspaper 1, 1994

Have you ever collaborated with political artists regarding regimes that affect other societies outside of the West?

One project I worked on was to go with Cat Phillipps to Bethlehem with a group of mainly street artists from around the world, including local Palestinian artists, and to take part in an exhibition organised by Banksy. All the proceeds from the exhibition stayed in Palestine and were to be used on education projects with Palestinians. We also all painted and pasted work on to the Separation Wall.

Would you collaborate with other musicians like the Kate Tempest project?

I’d be very up doing further projects with musicians and spoken word performers. It feels again that music and poetry are becoming a vital element in the struggle for a better world.

What is next for you?

I’m still reeling from the success of Jeremy Corbyn! There has never been anyone with his total belief in building a fair society leading the Labour Party. With Bernie in the US and Jeremy in the UK, we can build great grassroots resistance movements. I’m sure my work will reflect this hope for the future.

Extracted from GOOD TROUBLE ISSUE 23, the limited-edition print publication available NOW

INTERVIEW BY HARRIS ELLIOTT & RODERICK STANLEY / All artwork by PETER KENNARD

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.