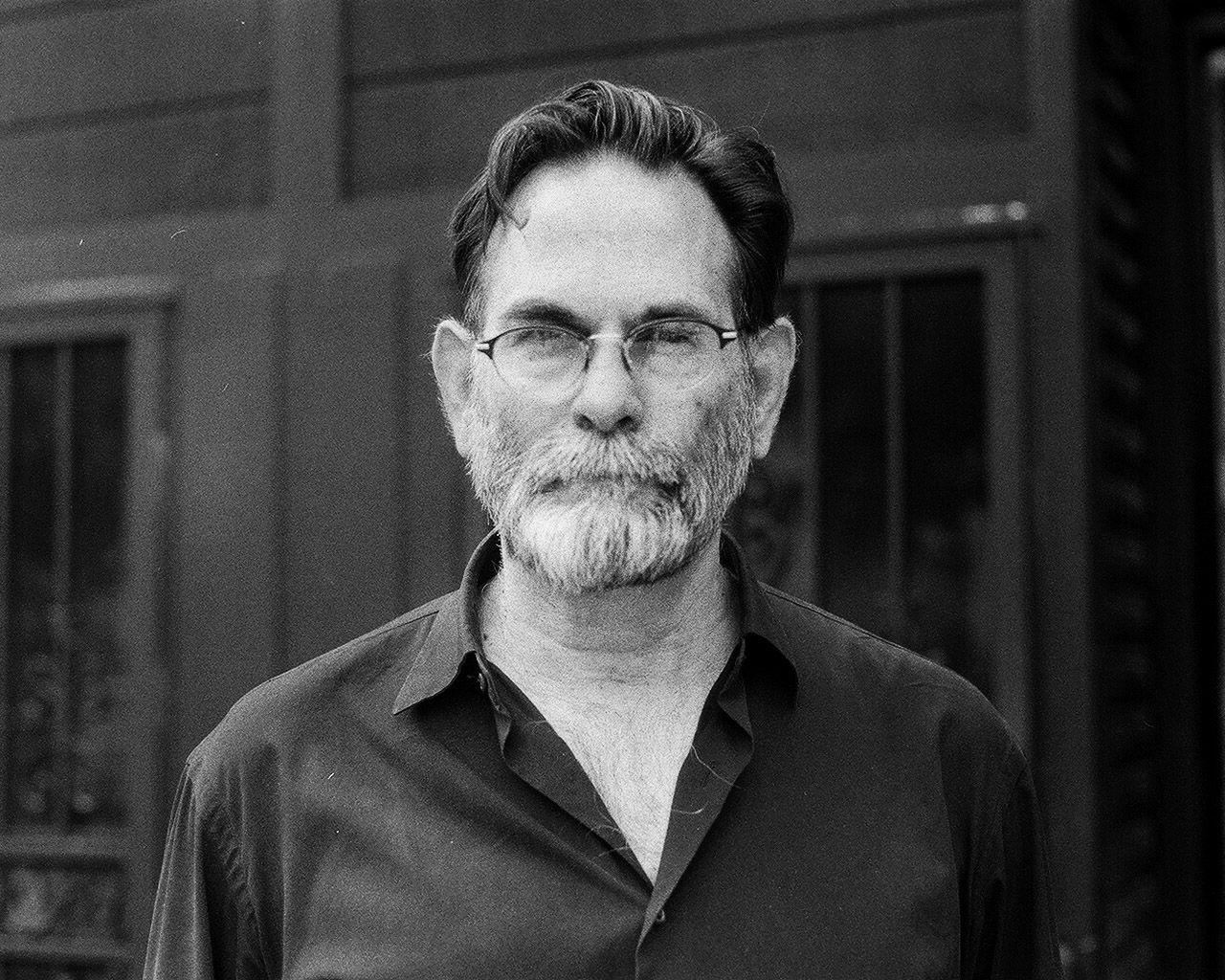

The Transmitter: Warren Ellis

Outspoken comic-book writer Warren Ellis on modern myths, our post-truth landscape, and why Nietzsche would have been ‘fucking great at Twitter’

Everyone I know is in some form of existential crisis, and it’s no surprise. We have a guilt-ridden addiction to our screens, our thumbs are sore from the scroll, and our minds feel like an overflowing mailbox. It used to be the unknown future that was terrifying; now, it’s the present – the fact that at any given moment, a piece of information could give us a nice little dopamine hit and dramatically change our lives for better or worse. No wonder we are anxious.

I spoke with Warren Ellis at How the Light Gets In 2018, a philosophy and music festival in a small town called Hay in Wales. Ellis is a cerebral, award-winning English comic-book writer and novelist (Transmetropolitan, RED, Gun Machine), and we talked about the power of narrative in the information age. With a weathered character, an emphatic voice and an absorbent mind, Ellis is a natural storyteller. If science-fiction stories are transmissions of what the future may hold, then Ellis is a transmitter, the carrier signal of the present.

You are described as a transhumanist. Could you describe what that term means to you?

Transhumanism is a term I like because it comes with interesting ideas and stories. I somehow disagree with what is intrinsic in the premise, which is that it’s on the way to something post-human, and post-humanism doesn’t convince me as an idea. Transhumanism, for me, is radical tool-use. We are all already cyborgs, the pieces might as well be detachable. When people tell me they’re against transhumanism, I ask them how they are enjoying the artificial soles attached to their feet in order to be able to walk in more difficult environments without harming yourself, or your glasses? These are all tools, all we’re talking about radical tool-use to extend the capabilities and possibilities of human forms in space.

“We are all already cyborgs, the pieces might as well be detachable.”

Technology is inextricably connected to human life, but to what extent has that relationship between tool and human changed with the rise of digital technology?

We’re going wide as much as we are forward, we scoop in new tools and the potential for new tools in order to move forward with them. The move from analog to digital isn’t a move as much as it is an expansion of the breadth of tools available to us. It’s additive and as we go forward we’ll discover new things. A friend of mine, Rachel Armstrong, posited the method to save Venice from sinking by using synthetic engineered seashells. Just raising the city up on a huge bed of seashell. That’s not something that was available to us even as a concept twenty years ago, and that will become a new tool in our shed and it’s not replacing anything. It’s a new potential, a new tool.

“Science-fiction is not a literature of prediction, sometimes it happens, but that’s purely by accident. It is the early warning weather station for culture. ”

Marshall MacLuhan famously stated that “we look at the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backwards into the future.” Can the genre of science fiction help us through the conundrum of modern times?

Science-fiction does away with the rear-view mirror. All pure science fiction is about the present day of the world. It’s about the human condition as it is today. It’s using speculations of the future as a tool with which to examine where we are now and where to go forward. Science fiction is not a literature of prediction, sometimes it happens, but that’s purely by accident. It is the early warning weather station for culture. There is no rear-view mirror, which is why science fiction is a difficult literature for some people to get into because it somehow feels unanchored.

Photographs by Ellen J Rogers

So, science-fiction is like a modern day myth? A warning for things to come?

Yes, science fiction works similarly to myth. It wants to transmit knowledge. Science fiction will offer conclusions about one speculative path we might take into the future. They’re not always framed as conclusions but they are. You’re invited to decide whether Brave New World is a good thing or a bad thing. Once you hold that conclusion, you learn something about a way we might be going and you decide if that’s good or bad for yourself. There’s knowledge within that. Myth has a similar mechanic. Human beings dramatize everything, up to and including the sky and landscapes. The earliest myths are about the shapes we think we see in [the stars] and the stories they tell as they wheel through the sky, which leads inexorably to navigation. If you recognize the stars and how they move through the sky, you can navigate past them. Myth and science fiction are fantastical stories about where we’re going. They’re about transmitting the knowledge for you to navigate your way there or away from the future.

But how do you get people to pay attention to the warning signs when attention spans are that of fruit flies?

Drama and conflict. How did sailors on the Danube teach people to avoid the terrible outcrop on the river that would suck people in? They created the story of the Siren, a navigational war myth to warn people of this outcropping of rocks. Science fiction works in similar ways. [Orwell’s] 1984 and [Huxley’s] Brave New World are the warning signs to avoid the rocks.

Do you think social media platforms like Twitter are ruining the form of storytelling and the transmission of knowledge?

Twitter is not a million miles away from when philosophers would write aphorisms and collect them into a book. Nietzsche would’ve been fucking great at Twitter. Of course, when he still had all his marbles and it wasn’t all psychedelics and syphilis.

“This is the dark side of telling stories. Every political campaign is about who tells the better story to some extent.”

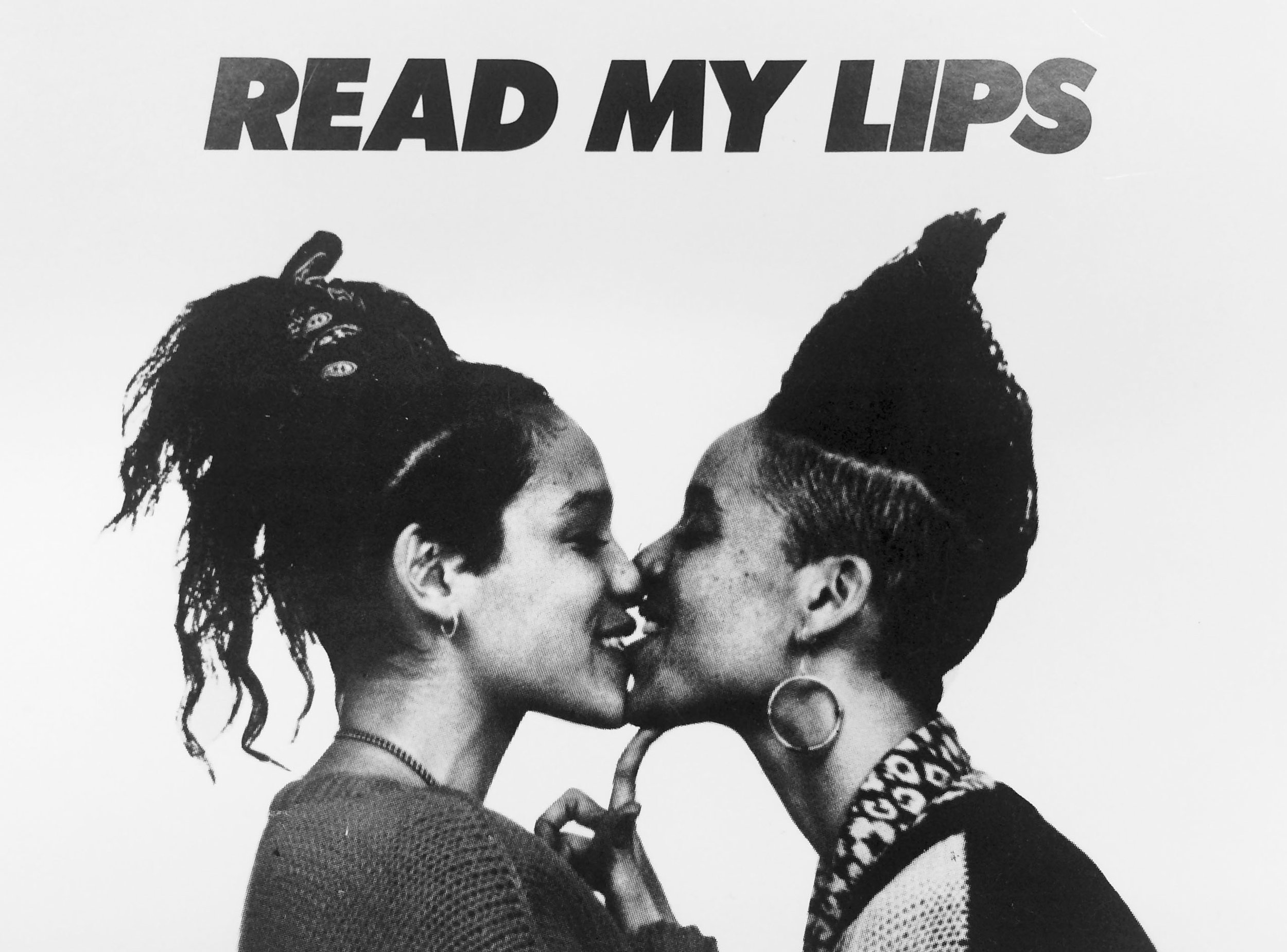

From Ellis’ Transmetropolitan

You wrote Transmetropolitan in the late 90’s. Transmet’s infamous gonzo journalist, Spider Jerusalem, would spout prophetic sayings like, “Lies are news and the Truth is obsolete.” Is finding ‘the Truth’ still relevant in an age of echo-chambers?

It’s a hard thing to talk about ‘The Truth’. Everything goes in cycles, and there are times where the concept of Truth is relativized out of existence by the right or the left because it’s inconvenient, because it’s difficult, because you think you’re reaching a higher plane by denying there’s no such thing as an objective truth. We’re in the post-truth landscape where we’ve been for three or four years and being true or being right doesn’t matter anymore. Michael Gove said [after Brexit] that what we’ve witnessed is the end of experts, which ties right back to Glenn Beck in the [United] States six or seven years ago saying, ‘you could listen to experts, or you could search your feelings and know what’s right.’

What are the ramifications of the end of expertise?

We’ve seen it. Every expert under the sun said Brexit would be a disaster and yet... Every expert said Donald Trump would be a disaster as the President and yet... This is the dark side of telling stories. Every political campaign is about who tells the better story to some extent. ‘Brexit’ simply told a better story. Donald Trump simply told a better story, a more affecting story, a more emotional story. And emotions particularly in this time and place tend to short-circuit logic…It’s something you see in storytelling in the last fifteen years, in a movie if everyone cries in the end, you feel like something important happened, whether or not the proceeding hour made any sense at all. [Trump’s campaign] was a story of resistance. Trump said, on the other side, you have a clearly corrupt person married to a clearly corrupt person who are part of this American dynasty that believe they should be in power just because of who they are. You know, it wasn’t dumb and they framed their antagonist very well. Lock Her Up. Lock Her Up.

“Most of America would consider themselves to be media literate because they know what Twitter is. But they cannot, in a post-truth era, recognize an obvious lie in the way that lies are currently dressed up. ”

So we are completely unaware of how much we are affected by strong narratives. That’s a bit scary.

There’s an argument to be had around the term media literacy, which is taken to mean, ‘oh I know how to use a phone, or how Netflix works’. Media literacy should be the study of how transmitted stories work on us. But most of America would consider themselves to be media literate because they know what Twitter is. But they cannot, in a post-truth era, recognize an obvious lie in the way that lies are currently dressed up.

How do you get people to be present to something that they are blind to?

Well, you can go to the word everyone hates: education. In America, it’s taken to mean elites from on high, teaching you shit you’re not interested in because they’re better than you. So you’ve got to start by reframing the term education in a way that does not mean elites reaching from up high tapping you in the shoulder and saying you’re wrong about everything. It’s hard particularly in America because democracy is so fine-grind. And so the political machines around democracy are tiny and numerous so there’s no longer one big machine you can resist against.

So what does one do in such a world?

Inside the bubble is an affordance and outside the bubble is a giant gate. Get out of your own silos and cross-pollinate.