What Is To Be Done? The Art of Resistance

Change is in the air! At the annual Armory art show in New York this year, former LACMA curator Jarrett Gregory presented 12 emerging artists whose work focuses on political and social issues.

While the theme for the Focus section show ‘What Is To Be Done?’ was selected long before the US election and Brexit referendum of 2016, the recent intensity of political upheavals has given it even more urgency; although as Gregory reminds us, "It is important to remember that the state of the world didn’t get bad recently—it got worse and more visible'."

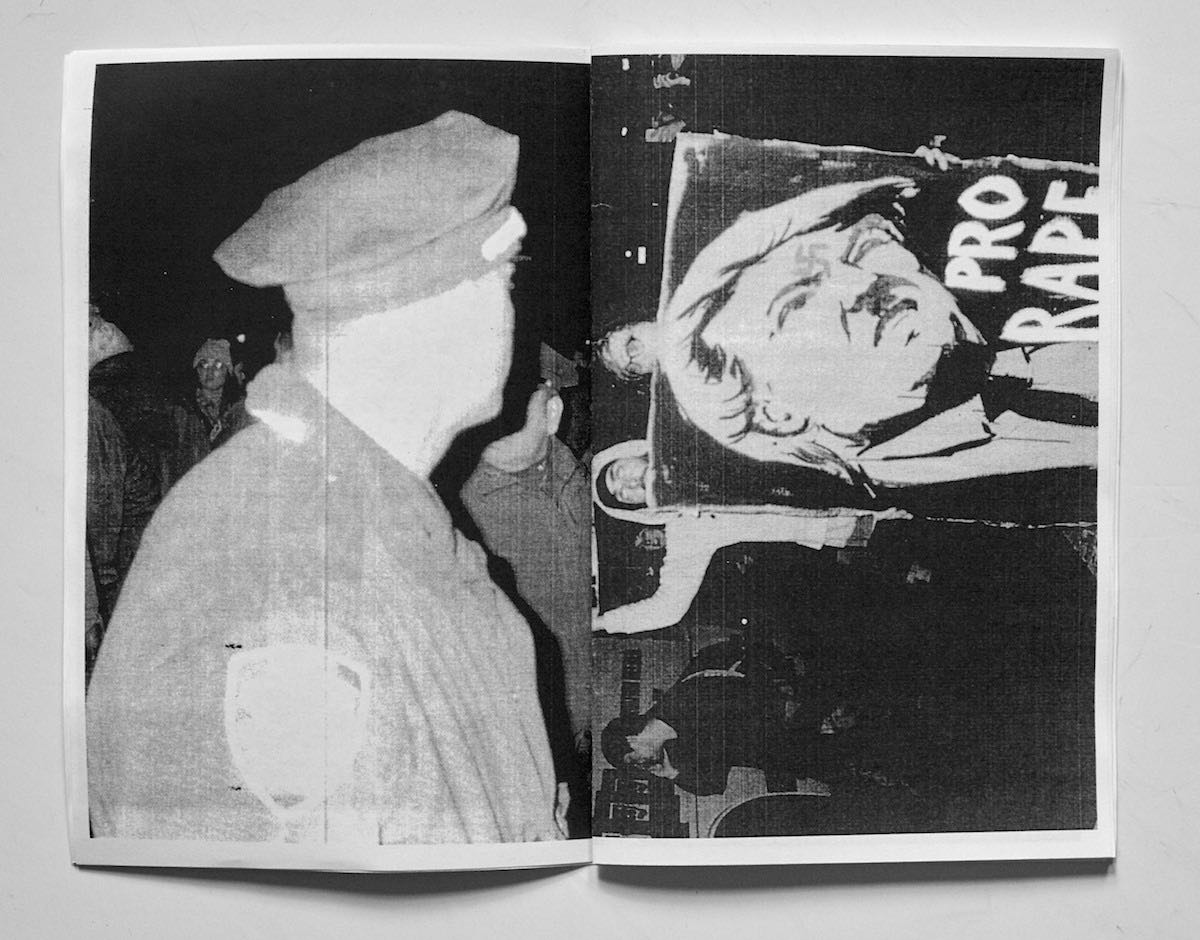

Teresa Margolles – Karla, Hilario Reyes Gallegos (2016). Transsexual sex worker beaten to death in December, 2015, in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico

Art featured included sculptures by impoverished Congolese plantation workers; Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama’s reappropriated jute sacks; Deana Lawson’s radical photography of the black female body; Mexican artist Teresa Margolles's arresting portraits, including a transsexual sex worker named Karla who was beaten to death in Juarez, Mexico, notorious for its levels of violence against women; Johan Grimonprez’s video about two people on opposing sides of the arms trade; and a project about the devastation caused by belief in supposed healing powers of rhinoceros horn, by Vietnamese artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen.

Good Trouble spoke with Jarrett about the importance of socially engaged art in 2017, the influence of her recent trips to Russia, Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and her thoughts on the question of what – indeed – is to be done?

GOOD TROUBLE: The theme of FOCUS 2017 was presumably arranged long before recent political events, such as the US election or Brexit. What made you decide social and political art was so relevant and vital at the moment? Presumably, it feels even more so now?

Jarrett Gregory: In the time since I initially conceptualized the section, the political situation has certainly emerged to the fore. I wanted to explore global causality and the inequitable distribution of power; these issues were of course ongoing long before Trump took office, but infrequently addressed. The social and political through-line emerged very much in response to the context. Art fairs are highly charged environments where people, by spending money, shape the art world; I wanted to respond.

“It is important to remember that the state of the world didn’t get bad recently—it got worse and more visible.”

In the months leading up to this project, I visited Auschwitz; a plantation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; the Gulag museum in Moscow; and the slave fortresses along the coast of Ghana. I wanted to bring together artists who, through their own unique practices, could help me piece together a worldview that reflects the ways that our cultures are fundamentally interconnected—I do not mean digitally. In our foreign policies, in our manufacturing and trade—really, in all of our decisions. These were the big questions around economy that I wanted to tackle in the context of the Armory. I imagine these issues will feel more pertinent to viewers today, though it is important to remember that the state of the world didn’t get bad recently—it got worse and more visible.

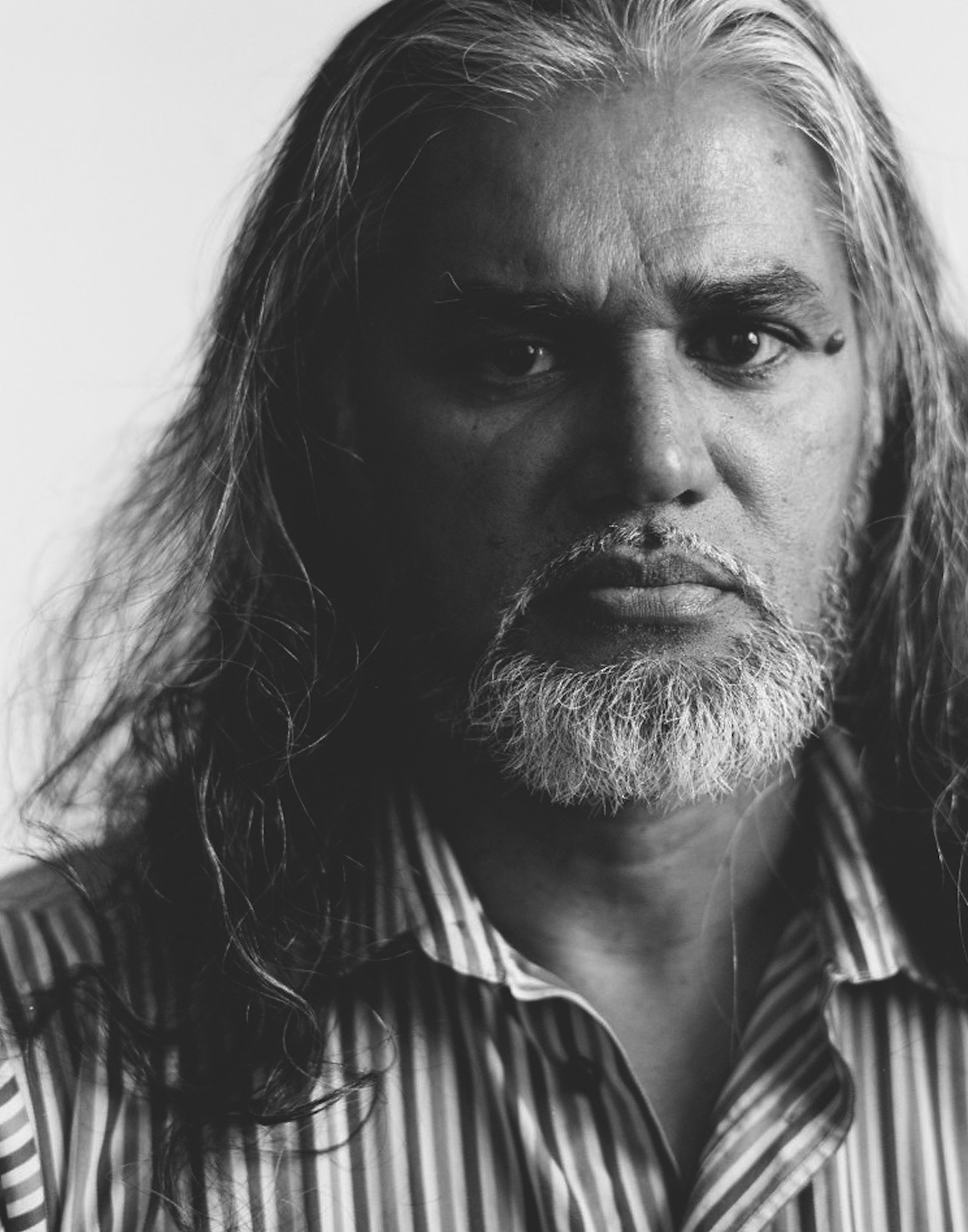

Tuan Andrew Nguyen

What in your view makes a work or artist 'political'?

The term ‘political art’ suggests that the work uses subject matter that is referential—iconography like flags, or the portrayal of presidents, for example. That is something that I would avoid, both in practice and in terminology. I think that when a work engages with its time and place it is inherently political, and I’m interested in a looser understanding of what makes a work of art political. The featured artists vary greatly in their approaches. When I first saw Deana Lawson’s photographs I understood intuitively that, at least to me, these were highly political works. The way that she pictures the black female body is radical. Her compositions not only reveal her prowess but I find them incredibly affecting, even disarming.

Deana Lawson

The CATPC presentation is another that is very important to me. I traveled to the DRC to visit with the artists; it was just two days after the riots in September when 17 people had died on the street in Kinshasa. I traveled from Kinshasa to Lusanga, which is in the jungle interior of the DRC, and I stayed in a mud hut in the village while I attended the four-day conference. I wanted to experience the project first-hand so that I could represent it appropriately.

“I traveled to the DRC to visit with the artists; it was just two days after the riots in September when 17 people had died on the street in Kinshasa.”

In general, we are very careful not to upset the balance when making our artwork or exhibitions, but when making our policies we destroy nations and cultures. The CATPC project is controversial because it attempts to reveal and actually alter the status quo; I appreciate that it risks a lot for what I believe are very high stakes. To me, this project is timely because it challenges our understanding of what a work of art can—and should—do.

Cercle d'Art des Travailleurs de Plantations Congolaises (CATPC)

With these trips to DRC and other places such as Russia, what experiences there gave you insights about art, power and resistance?

At first impression, the DRC and Russia seemed to be completely disparate places. On the plantation, I witnessed the reality of capitalism: how the prosperity of the West was only possible through the wide-reaching enslavement and domination of other people. And in Russia I intuitively understood the desire for a different system, why they turned to Socialism, and why that failed. In terms of art, the two places couldn’t be more different – in Russia there is an underground scene of young people making shows in apartments to avoid censorship and making work without access to a market.

“In Russia there is an underground scene of young people making shows in apartments to avoid censorship and making work without access to a market.”

In Moscow, I benefited from an incredible network of artists, writers and curators. The DRC on the other hand has a great history of creativity, which has largely been eradicated by the plantation system. The Pende people were famous for their artwork, such as their masks. Many were forcibly relocated to work on the plantations and their cultural objects were looted from them. In the DRC, creative expression is a privilege that almost no one has. And so it is particularly meaningful to present sculptures by the plantation workers in a context like the Armory Show; it goes against everything that the plantation system has been is built upon.

Johan Grimonprez – Installation view of | blue orchids | 2017

What Is To Be Done? asks the show title. What role do you think art and creativity can play during moments of social upheaval or crisis?

It is my personal opinion that social crisis is the status quo, so I don’t think that the role of art changes. I studied the history of art partly because it was a unique way to understand the history of the world, and I believe this principle holds true for contemporary art as well. Art offers us a meaningful and expeditious way to understand one another. I also believe that we can use the art market to enact positive change.

Beyond that, I think one’s role is highly personal, so I can only speak for myself. In my practice as a curator I’ve come to appreciate that traveling in itself can be a political act if you are building relationships and understanding around the world. Even more so when the US foreign policy is what it is today. I am compelled to present work that grapples with big questions, but those could be topical or timeless.

ACTIONS

Support Women's Rights around the world with Amnesty

Why not adopt a rhino and help support the WWF in their campaign?

Learn about the Global Arms Trade Treaty at OXFAM

Find out more about the Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC)

Writer, editor and consultant based in London /New York