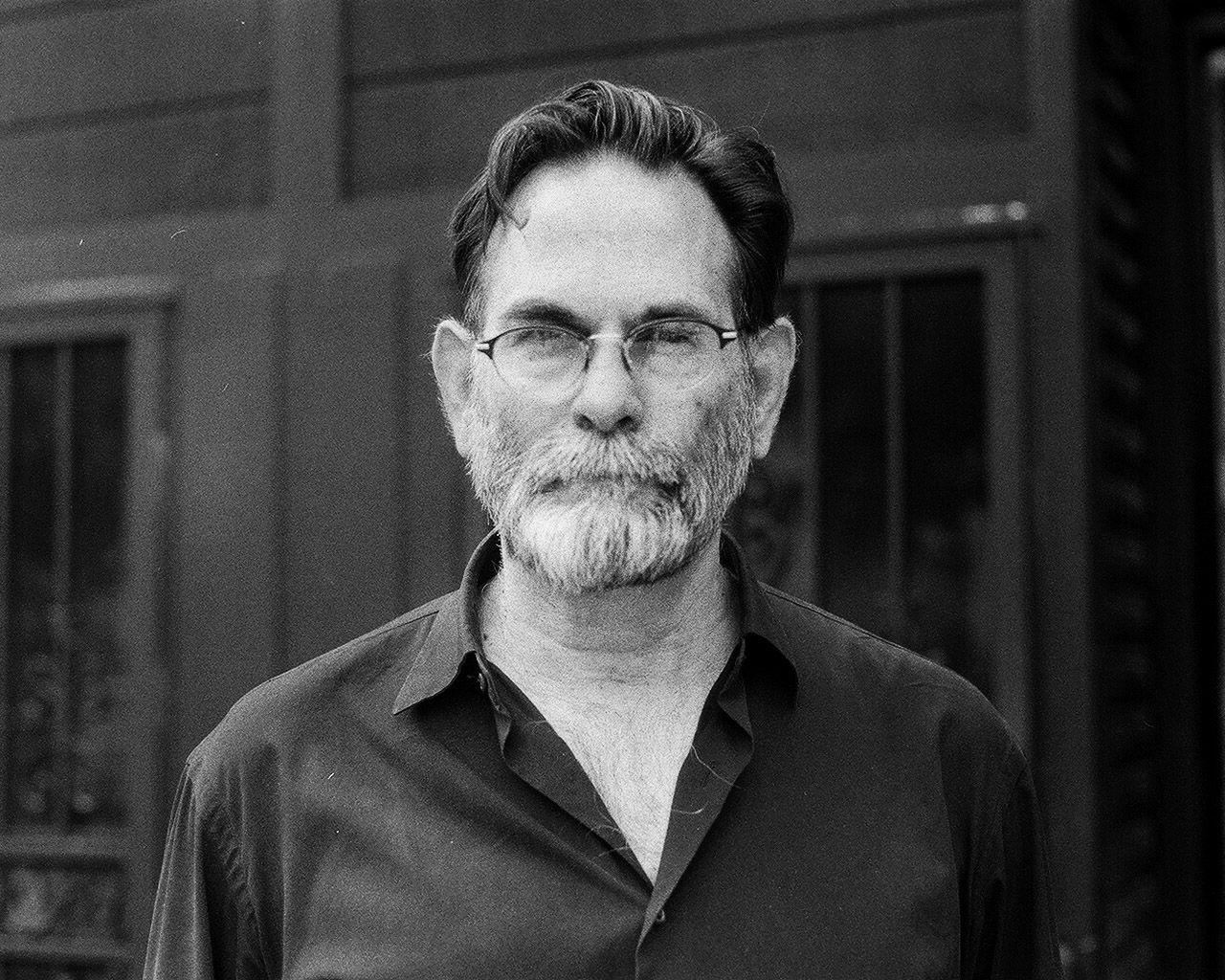

Yoshua Okón: Future Shock

Chalton Gallery exhibits contemporary British and Mexican artists with the aim of initiating a dialogue and building enduring creative relationships between both countries. This fall, the gallery presents Mexican artist Yoshua Okón’s first solo exhibition in the U.K. entitled Future Shock.

As an important figure in shaping Mexico City’s contemporary art scene, Yoshua Okón co-founded the former artist-run, non-profit space La Panadería before establishing SOMA, an art organization, independent educational space, and cultural forum for Mexican and international artists. His work focuses on what seem like absurd political and social issues affecting North America: excess consumption, widespread dispossession, and blind nationalism. He blends documentary, fact, and fiction, incorporating staged situations, documentation and improvisation, to ultimately question reality, our perceptions of ourselves, and our morality.

Future Shock, an installation featuring three moving image works from various stages of Yoshua Okón’s career, is the artist’s attempt to reveal the sociopolitical post-truth reality. He uses narrative techniques like reenactment and simulation to explore, subvert, and destabilize social dysfunctions. All three works - Freedom Fries: Still Life (2014), Canned Laughter (2009), and The Indian Project: Rebuilding History (2015) – are marked by a disruption of truth, a blurring of the boundary between authenticity and inauthenticity, the seen and unseen, fact and fiction, and a critique of such mechanisms as capitalism and consumerism both socially and geopolitically. As viewers navigate this exhibition, they’re left to find themselves in the non-linear world Okón has created.

Yoshua Okón, Canned Laughter, Lightjet c-print. 39 x 54.6 inches, courtesy of the artist.

You’ve played a pivotal role in shaping the contemporary art scene in Mexico City first with co-founding Panadería and then with establishing SOMA. How does Mexican culture influence you as an artist? Do you feel a sense of responsibility to representing it?

I do care deeply about my community, but I think it’s important not to confuse community with the Nation State. I don’t particularly identify with the Nation State construct. Nation States are not specific enough to represent us, nor are they universal enough for us to identify as citizens of the world. It is a terrible middle ground that leaves us floating in a void and ultimately alienates us.

As an artist, what is your preferred medium?

I see my practice as a hybrid. It is a combination of performance, video and installation. All of these three aspects are as important, and I wouldn’t prioritize any of them.

Canned Laughter Video Still. Courtesy of Okon Studio.

Your work plays upon artificiality and reality to critique social and political issues. Arguably, you’re transgressing boundaries via both narrative techniques such as reenactment and simulation and themes such as nationalism and power. What interests you about these narrative techniques and how do you feel they lend themselves to the subjects you’re addressing?

The tension between fiction and actuality can potentially give us critical distance from familiar aspects we don't tend to question. My work departs from the assumption that, in consumer culture, our sense of reality is highly mediated and is mostly informed by our exposure to mainstream media and advertisement. When confronted with a particular tension between fiction and actuality, our normalized sense of reality gets shaken and our mind’s usual reaction is to activate and automatically search for meaning. This has the potential to destabilize predominant narratives (the “natural order” of things) and gives us the opportunity to creatively re-think and reconsider our ideas about reality. In other words, it gives us the opportunity to formulate our own personal notions. In this sense, systemic social dysfunctions, which have become normalized to the point that we don't see them, can potentially gain visibility. This is what I hope the viewers experience is when confronted with my works.

Canned Laughter Installation View Via Farini. Courtesy of Okon Studio.

In Canned Laughter (2009), you allude to televised laughter as at once a means of exploitation and inauthenticity, that emotions cannot be truly reproduced via technology. How are “globalized exploitation” and a lack of truth in digitized emotion connected to you?

The central image of Canned Laughter is a face (in this case a maquiladora worker’s face) producing the sound of laughter without actually laughing. This image is meant to be a metaphor of neoliberal post capitalism: with its spectacular, shiny and clean surface creating the illusion of prosperous stability, and its hidden dark and violent underbelly. The lack of truth lies in the message that is being powerfully projected through mainstream corporate media that tells us that we live under a fair, functional and sustainable system. Global capitalism is generating a lot of misery in the “forgotten” parts of the planet, and it’s destroying everything on its path to environmental collapse.

Freedom Fries Still. Courtesy of Okon Studio.

In Freedom Fries: Still Life (2014), you’re pointing towards the body politics that arise in a discussion of consumer culture and food. Do you find this to be geopolitical, as well?

Yes of course. There is nothing more globalized than junk food. Even if this originated in the US, you can find McDonald’s, Coca Cola, and other junk food brands in the last corners of the planet. The resulting obesity and diabetes epidemics are global as well; they don’t pertain to any particular nation. It is a geopolitical issue. Consumer culture is global.

The Indian Project: Rebuilding History (2015) focuses on the community of Skowhegan (Maine). What inspired your work with this community to create this film and how did the process of collaboration work?

In 2014, I was resident faculty at Skowhegan, a summer art school in Maine, USA. While there, Jeffrey Gibson, a fellow resident faculty member who is Native American, gave an artist talk and mentioned that New England where Maine is was the site of the worst genocide against Native Americans in the country. Right next to the school, there is a town with the same name. The town's identity is supposedly built around Native American Culture: the town's logo, the town's public signaling, their sports teams, etc. And they also have an 82-foot tall wooden statue representing a Native American, which they refer to as “the tallest Indian in the world.” A sign narrates the town’s history in which it is alleged that in the 18th century all of the state of Maine, and beyond, was sold to the English colonizers for bags of provisions including peas, strong water, etc. (an image of the sign is included in the video). After hearing Jeffrey's talk, I started wondering and my research began.

The Indian Project Video Still. Courtesy of Okon Studio.

Effectively, in the town, there is no trace of any pre-colonial culture or ancestry that I could find. What I found out is that the lumber industry collapsed in the late 1960's due to over-exploitation, and at that time, the town's Chamber of Commerce decided to invent a “Native American” identity as an attempt to boost the economy by attracting tourism. While I was there, a fundraising campaign to restore the statue was taking place. I approached the Chamber of Commerce members in charge of the restoration and asked them to conduct a program about the town's identity and the history of the statue at their local TV station. Once they agreed, I also gave them the general suggestion to perform a “Native American trance ceremony,” assuming fictionalized versions of such ceremonies are so deeply embedded in the US imaginary through cartoons and other popular media, that they would automatically know what to do.

I encountered a big everyday-life collective fiction unfolding in that town (which, I have to say, is a nation-wide collective fiction), and my role was to ask some of the representatives of such fiction to perform it for my camera as well as to push it a notch further by asking them to include a “trance ceremony.”

The Indian Project Video Still. Courtesy of Okon Studio.

Geopolitical (mis)representation on the macro and micro levels are quite evident in this video.

Yes, for sure.

The title is an interesting concept. Rebuilding history; redefining what’s past in the present; the perspective of history and the idea that who’s in power writes it; different truths. What are you trying to suggest or critique about history, truth, and reality here?

Yes, the title is taken from the slogan of the campaign that the chamber of commerce used to raise funds for the restoration of the “Native American” statue in Skowhegan. It is a sort of ironic appropriation that points to the fact that history is an artificial construct. Colonial narratives in the US have systematically made invisible and denied the Native American genocide, that’s what’s being critiqued in this piece.

You’re attempting to “unveil the political and social post-truth reality” in Future Shock. You feel we are in the post-truth era?

Well, full access to truth has always been out of our reach. But I do think that in this era, where we are being massively bombarded with highly sophisticated advertisement and propaganda, we are definitely being taken even further away from truth. Our level of alienation is quite high in consumer culture.

The Indian Project Installation View MUAC. Courtesy of Okon Studio.

Would you consider your work to be “political art”? What are your thoughts on the intersection of art and activism and the creative community’s role in engaging or reflecting sociopolitical issues or raising awareness?

Activism has specific agendas. There is a specific political goal that wants to be achieved. Art, on the other hand, has no specific agendas. It, of course, can be aimed at provoking reflection around specific political issues, but it has no agendas. Unlike activism, art’s outcome cannot be quantified or measured. It does affect the world around us, but in ways that can’t be calculated. Making art is not about convincing anyone about anything. It is about reflection, about free, creative, and critical thought. In this sense, art always has a political dimension, as long as “political” is understood in the broader, original sense of the word, as in how we relate to each other with regards to issues that concern us all in society. There may be artists that are more aware of this than others, or some that care more than others, but such political dimension is inevitable in art.

Art is a form of social communication and therefore artists, consciously or unconsciously, always take positions. I don’t think that it is the responsibility of members of the creative community to specifically raise political issues in their work, but I do think that it is our responsibility to be aware of the nature of representation and of the fact that art making means to automatically enter a political arena.

Future Shock is at Chalton Gallery, London through November 10th.

Chalton Gallery will host an artist talk with Yoshua Okón on November 3rd at 4 p.m.