Behind the Curtain: Jeff Bierk and the Art of Empathy

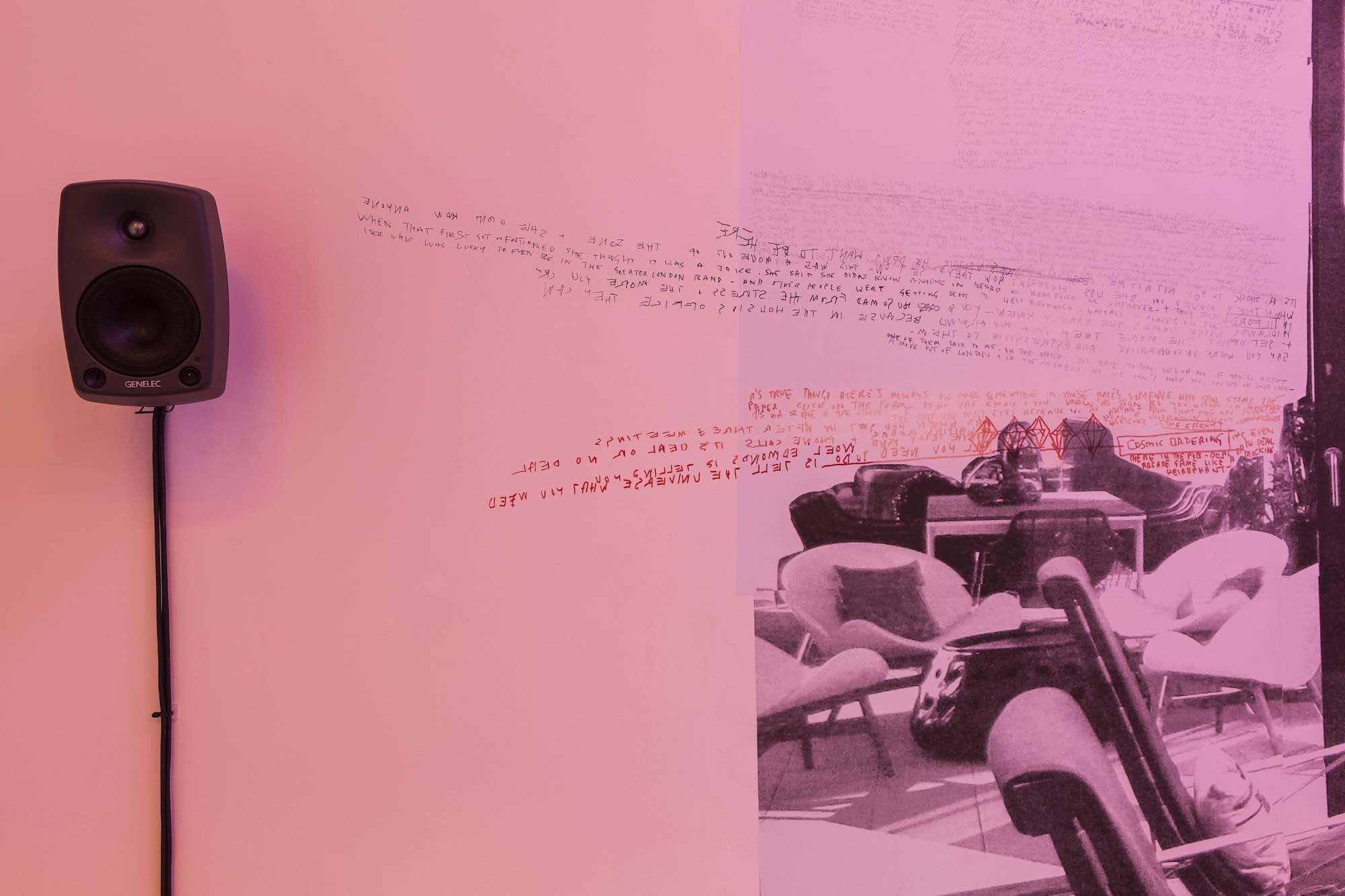

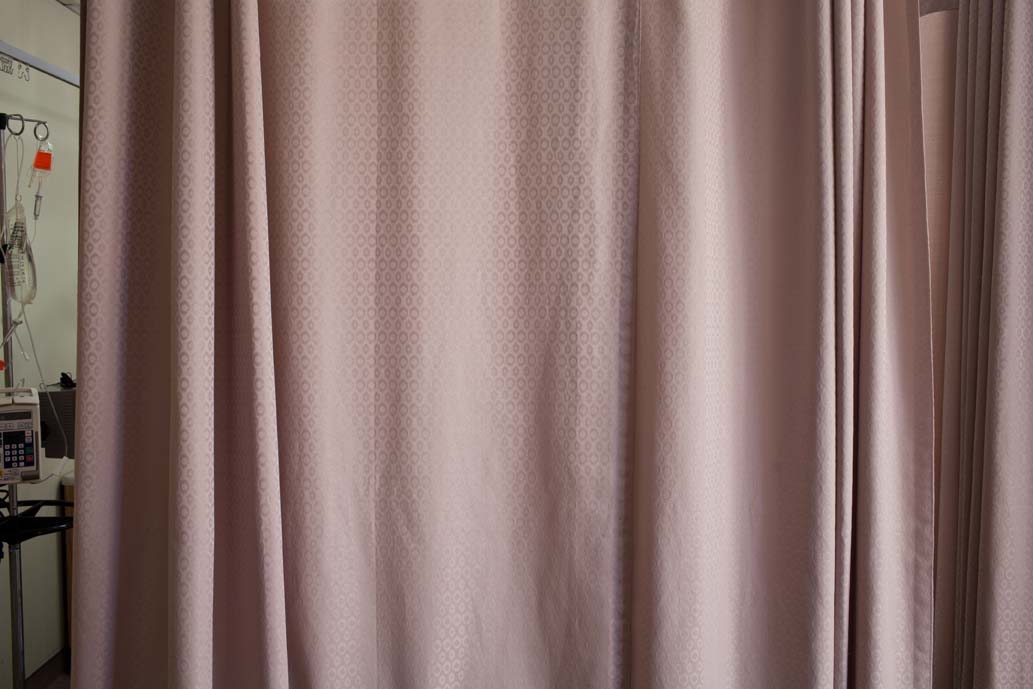

About an hour's drive from Toronto, Canada, there is a small community called Grimsby. This past December, I travelled to Grimsby to view Jeff Bierk’s Curtain, curated by Matthew Ryan Smith – an exhibition of hospital curtains Bierk photographed in 2009/2010, while his lover was in hospital dying.

Included with the images of curtains, there are also his more recent and commonly known works of his friends, a video and a large photo album with images from his childhood up to the present day. Bierk's friends are considered collaborators to the work, not art subjects. They are also people who live with addiction and poverty. The serenity one experiences within the space reminds the viewer of the necessity of accepting death and grief.

Me And Blue, Photographed by Sammy, Checker Park, September, 19, 2016

This small-town gallery is housed in the same building as the public library, and the setting encourages public displays of learning, growth and empathetic community-building in a way that larger cities lack. I spoke with Bierk to find out his thoughts on the experience of holding an art show in a rural community, interacting with the population of the area, and how engaging with people from smaller centres can affect change… and help us to be empathetic neighbours.

GOOD TROUBLE: Your art practice gives voice and esteem to people who live with difficulties such as mental illness and addictions. What do you see as the role for your work when it is viewed in a gallery setting? Is there an expectation of the gallery to also positively commit to community engagement?

JEFF BIERK: I don’t think my work gives voice to my friends as much as it points out and exposes all of the ways in which they are named and spoken for. Nothing in my work ever points to my friends being mentally ill, or having addictions – those assumptions are always brought on by the interviewer, the critic, the audience, the viewer. The evidence of that is in this question. So, I guess the work points out these assumptions, reveals them.

My work has a whole life outside of the gallery, and the gallery’s kind of the last place I think of it being. But when it shows in a gallery, one of the best things it can do is challenge dominant notions of beauty by offering my own understanding of what is beautiful. I think that’s the main thing, and to spur discussion about new relationships, new ideas about collaboration, ideas of community.

Curtain #9, October 18, 2010

As for galleries, and expectations on community engagements, I don’t want to paint everything with a single stroke, and really I don’t know much, I’m not an expert. But in Toronto, I don’t think that culturally there is currently any expectation of the gallery to positively commit to community engagement – at least among the major commercial galleries that are determining what is cool, popular or sought after. It is important to look at how galleries function in their neighborhoods, who they are for, who the art is for. What makes community engagement impossible for these major commercial galleries, is that they are often at the forefront of gentrification – after them come the coffee shops, the boutiques, the condos. Gallerists are literally the first people to come into a neighborhood to make it cool, to make it profitable. So, in this context, it’s impossible for positive engagement with community, unless it’s with the business community, allies in taking over the neighborhood, you know? Like solidarity amongst gentrifiers. I see a lot of that.

So, I think also, that the idea of community engagement depends on your definition of community – who are you conversing with? Who are you sharing with? Again, I’m only speaking to Toronto, and not to its whole, but it feels like people are segregated and the art world galleries are exclusive to the monied. We live in a city where so many communities exist, but those that don’t centre profit struggle to survive and are often made invisible or displaced. A lot of gallery spaces can feel exclusive to people in the “art world,” let alone people outside of that bubble.

Curtain, Grimsby Public Art Gallery, Installation View, Photographed by Jay Shuster, 2017

There are definitely galleries that are working to change these things, and there are some really good community arts projects and initiatives, galleries working with the community, galleries reclaiming gentrified spaces – they are often devalued, or less important, because they aren’t pushing art that is considered a “high-end luxury item”. And it’s getting harder and harder for these spaces to survive. If you look at what happened to Blank Canvas, a small gallery just a block away from where I live, that struggle to survive is very real. The police used tazers on people coming together there to party because they didn’t have special events permits – the anti-black racism in that violent act was apparent. I’ve seen parties get shut down by cops, but never seen that use of force in a gallery space full of white people.

I don’t make it as many openings as I would like to, mostly because I work Thursday, Friday and Saturday every week and have other regular commitments outside of my job. There is so much good art being made in this city right now! I’m really excited to see Tau Lewis’ solo show coming up at 8Eleven, Kent Monkman at UTAC, and Jalani Morgan’s work in a group show at the Gladstone Hotel.

Jimmy (Curtain), Visiting Donny, June 22, 2015

I just did some work with Claudette Abrams, the Visual Arts Coordinator for a group called Workman Arts – an “arts and mental health organization known internationally for its artistic collaborations, presentations, knowledge exchange, best practices and research on the impact of the arts on the quality of life of people living with mental illness and addiction.” I think they are a really beautiful example of art and community engagement and I feel a connection to my values, and my understanding of art, collaboration and community. And there is a parallel to the kind of work I’m making or doing In my own life, I work outside of institutions, in the most renegade way. I take some of the things people ascribe to social work, or to community art projects – collaborative work – and I do them in my weird life, and the way I’m able to fund that is through my jobs (retail sales at a camera shop, photo gigs), and sometimes through commercial galleries.

Curtain, Grimsby Public Art Gallery, Installation View, Photographed by Jay Shuster, 2017

Whose idea was it to connect to the community of Grimsby by way of the local hospice?

Rhona Wegner, the Director of The Art Gallery of Grimsby, is incredible and she connected the gallery with the The McNally House Hospice – a local hospice, as well as the Niagara West Community Charter. Their initiative is to increase awareness and access to resources around death, dying and loss, as well as to demystify death. Both of these groups work in their communities to destigmatize death and foster an openness – they’re doing real emotional labour.

Unfortunately, I could not make it to the open forum with the gallery of Grimsby, yourself, Matthew Ryan Smith and the hospice – what do you think was the most important takeaway from the discussion?

The most important takeaway for me wasn’t something we talked about, rather the experience of having the discussion. The talk was so beautiful, and for me it was very satisfying and engaging. We sat in the beautiful, open gallery, behind a row of these photographs of hospital curtains. The room was filled with around 20 people, mostly older women, with the exception of two men. I felt a little out of place without the freedom of anonymity that the city gives me. At first I definitely judged the room, I judged some of the people there based on how they looked, their age. The engagement and openness that followed shattered this judgment and the conversation was incredible.

There wasn’t any sort of conclusion – just an open-ended discussion of death. First I spoke about my experience with death and loss, told the stories behind the photographs, and about what the work is trying to articulate – my own grief, where it was born, how it has shaped me, how it’s changed, how I’ve healed and grown. About trauma, beauty, about the hospital, about cancer, drug addiction, feeling isolated in a small town, and of course death. Lost friends, lost lovers, lost family, surviving. Grace.

Donny, Silk #2, 2013-2015

It was so beautiful to be in conversation with that community, and to see a way to collectively access an emotional connection. It wasn’t held up to any idea of what art is, or any idea of monetary value. There were no academics, critics, just regular people in discussion about their encounter with my work, and ultimately about their own experience with community and with death. I found it to be exciting. The women who work at McNally House Hospice in palliative care were so impressive. I admire so much the work that they do that often goes unrecognized, their open-mindedness, their compassion and understanding, their love. They provide a space for people who are dying, and work with families and with people on an individual basis to let people self determine how they die. They make it as comfortable as possible. They advocate for the terminally ill. They work to destigmatize death and dying, “Focus is placed on the physical, emotional, spiritual and psychological needs of the resident and their loved ones.”

I guess for me, the most important takeaway was the power of conversation in smaller towns. The openness in conversation at GPAG really made me consider the work that needs to be done in smaller communities. I think of how incredible it would have been if that kind of conversation had been happening in Peterborough where I grew up. Life might have looked different for me.

Curtain #1, December 1, 2009

As a young person, I had a very serious addiction. I think about the inability of my parents and their community, to understand addiction and poverty – all the anger or shame attached to it. It was as if my addiction, my failure to “succeed”, my struggle, was somehow a personal failure of my parents, not the failure of a community. My parents were coming from a culture with fairly repressed middle-class anglo sensibilities, that didn’t know how to interface with addiction, and that's not to blame them, it’s just to say that they had an inability to talk about it, to understand it, and to deal with it. The white middle-class mindset tends to designate who is deserving of care, compassion, kindness – they love to judge. People need to distinguish themselves from the “undeserving poor.” Poor people are blamed for being poor, people with depression are blamed for their depression, addicts are blamed for their addiction. And instead of communities working to know each other better, to open up, to love, you have whole industries – be it prisons or social work – based on criminalizing certain people, and profiting from illness and addiction.

One of the biggest barriers to political and social change in the communities I’ve been a part of is that white men can’t speak to each other or listen to women – and yet have so much systemic power. Not only do we have decision-making power, we are also on the frontlines of industries that poison the land and undermine the rights of indigenous people – these are labour forces that are full of addiction, where people get cancer from the very work they do. Our utter inability to discuss emotions and the reality of death surely enables us to keep from reckoning with what it means to be killing each other and ourselves, and so we can keep working at these toxic jobs. Maybe it sounds lofty, but seeing a few men begin to converse and listen to women at the Grimsby Gallery made me imagine all the things that could change if white men learned to be present to our emotions, fears, pain, mortality.

Cree's Arm, Process, 2014-2015

As an artist who created a very intimate portrayal of sincere love as life leaves the body of the loved, how does it affect you to reveal your own grief? Why is it important for communities to participate in death?

I think one of the biggest gifts from Death is for the living to be vulnerable with each other as we experience death in each other’s presence. The trust that death has the potential to create between people, and the space it creates for expression between us can be life-giving – the openness and understanding that people usually come to together through shared grief should be recognized. Whether through art or not, I’ve always revealed my grief, either in volatile ways or in generative ways. After a long struggle with it, my grief isn’t boiling and toxic any more – it comes out in waves, it’s softer, it’s changed. I have energy for the grief of others.

Of course, when people don’t talk about death, grief becomes so isolating. The emotional labour involved in the part before death, taking care of someone who is sick, someone who has a mental illness, someone who is struggling, is usually very private, can involve shame, and that labour is most often put on the backs of the people who will be most impacted by the loss of the person – women, partners. That is something that should be better acknowledged or recognized in community.

Curtain #13, October 18, 2010

On that note, emotional dialogue or vulnerability between men in the community could change so much. I look back on my own life and where I grew up – my relationships with other men, with friends, with my father – there was so much pressure to fit the mold of masculinity, to be strong and not vulnerable. My father died when I was young, and we weren’t ever close. I think I was afraid to be my true self to him, afraid to be soft, to be hurt, to be sad, to be struggling. I felt different, I felt like what I was – how I felt, my body – wasn’t good enough. And especially with my friends, any softness or femininity was met with violence and ridicule. I grew up being afraid to be my true self, and eventually losing all sight of what that was or who I was. And the roots of my addiction are less about the trauma I experienced with the death of my parents at a young age, and much more about how repressed and hurt it felt to try and fit into a patriarchal understanding of what it meant to be masculine, to be a man. I think a lot of that emotional repression is rooted in men’s fear of talking about death and loss.

Andrew Anthony Murphy, Cyanotype & Sky, 2011-2017

How did this form of community engagement, being open about the process of death and grieving positively effect the exhibition Curtain? Could this type of show exist in a larger urban centre like Toronto, or do you think with it being held in a smaller community it was better received?

The engagement with this show was very exciting for me – it felt like there was a real exchange. People came to the work honestly. They weren’t engaged with a scene, or with me as a person in a scene, but with the work itself. The work, which was in conversation with itself, opened up conversations and made connections with the people that viewed it.

There was a women, a towny, who came into the gallery with her young daughter. They walked around, quite quickly, and as they took in each photograph, she said, “Oh! Wow, look at that.” They got to this huge projection of Jimmy and she said, “Look! Isn’t that beautiful!” This made me so happy, because Jimmy’s beauty that is the foundation of that image is so rarely seen, and hardly ever articulated in this way, with such enthusiasm and truth. For her to see it so clearly was so nice, it had such an impact on me. I was like, “Finally!"

Curtain #12, October 25, 2010

The show could work anywhere. Community is always the prism through which you see the work. There are different opportunities that different rooms and places allow, and that’s part of what’s interesting about showing work in different places. It’s not site-specific work. The people who come to see the show in different places will have a different relationship with it, that’s the beauty of art.

Do you think larger urban centres like Toronto can look to this form of community engagement with art to open up dialogues about addictions, illness and loss of life?

Yes, definitely. But right now it’s pretty hard, because of the cost of living and rent being so high. People have less free time, less access to gallery and community space. So, art becomes a luxury, it becomes exclusive. At the very least, galleries feel a pressure to sell work or monetize events so they can pay their rent. So, there are a lot of ways in Toronto that art and art spaces are commodified. We are so lucky though, for all of the artists and spaces working against this, and making space for artists to talk with each other and communities. I am tuning into more and more of it, which is great. Xspace, YTB Gallery, BAND Gallery, The Black Artist Union, TANGLED Art + Disability, Double Double Land, Gallery 44, 8eleven to name a few places. All those places regularly engage community about all sorts of topics.

Curtain #8, October 25, 2010

Is it the role of the artist, or curator, or gallery to engage with the community? Or is this something that comes when all three work together?

I mean, again, it depends on the community, the artist, where one’s coming from. But I think because galleries are the ones that are in a particular geographic location, they can have the most sustained relationship with the surrounding communities. In the case of this show, Matthew Ryan Smith curated it, and what he did was connect me with the Grimsby Gallery. Because Rohna and the Grimsby Gallery are so community-minded, they considered who the work might connect with, and then organized events to facilitate that. The word “community” gets thrown around, and again, I think it’s important to be clear on what people mean when they say that word.

Good Trouble is a platform to showcase cultural practices and works of resistance. Within your work, I see great care of spirit: a subtly acute form of resistance, intense but like a whisper – would you like to say anything about whether you think your work is resistance? And why?

My collaborators’ bodies are often turned into symbols of something other than themselves, and I’m actively, with my work and through conversation, trying to attack the assumptions that lead to that. If anything, my work is in resistance to dominant notions of beauty, in resistance to patriarchal definitions of masculinity. The work makes room for emotion, which I think is necessary.

Jeff Bierk – jeffbierk.com and on Instagram

Grimsby Public Art Gallery – grimsbypublicartgallery.blogspot.com

The McNally House Hospice – www.mcnallyhousehospice.com

WorkMan Arts – www.workmanarts.com

Art writer and curator based in Toronto, Canada.