The Guildford Sit-In: May 68 in the UK

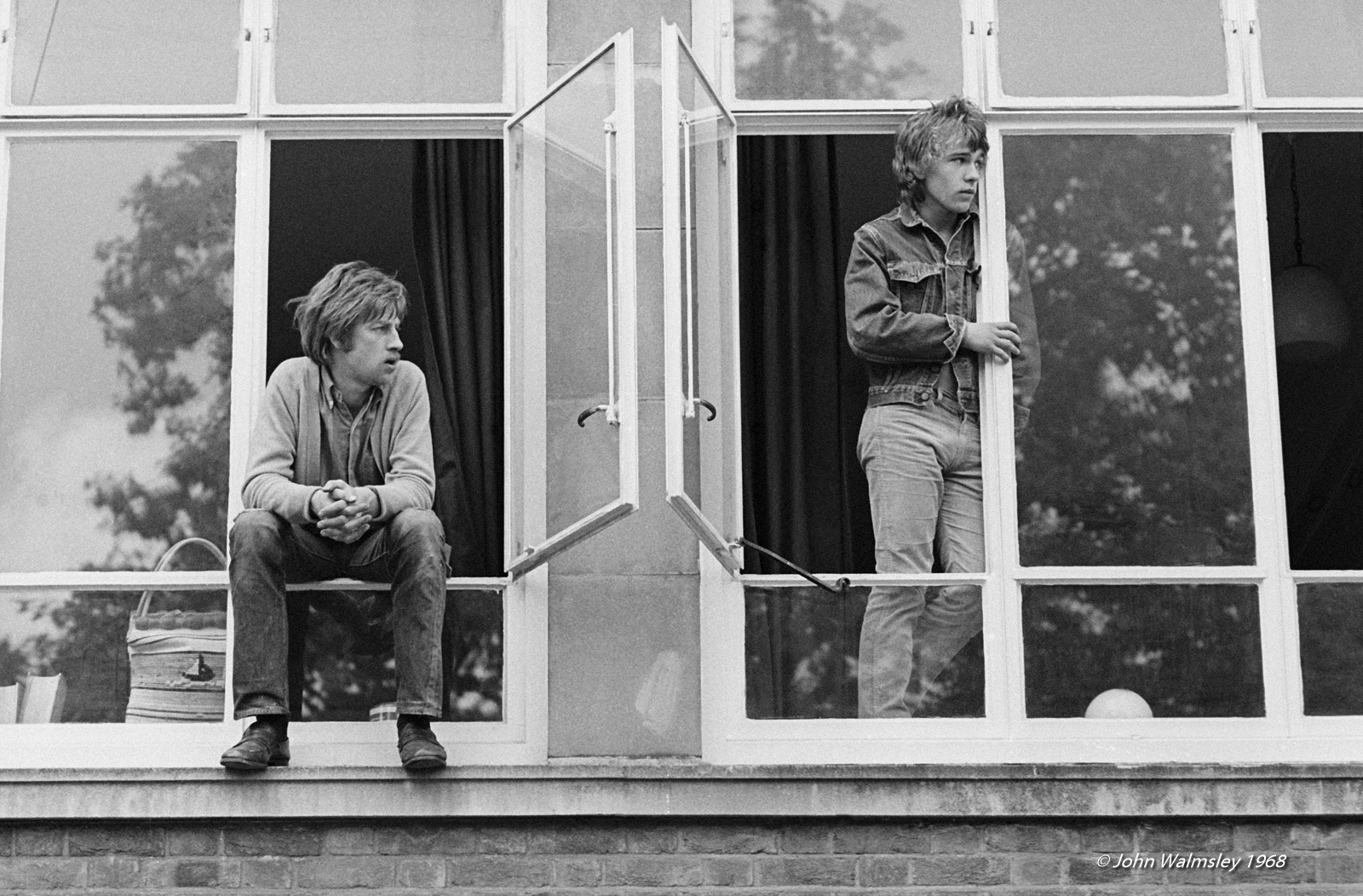

50 years on, the Parisian student uprising of May 68 is well known… less so are the sit-ins that took place in the UK at that time, including the country's longest ever at Guildford School of Arts, as documented by photographer John Walmsley

The work of British documentary photographer John Walmsley is a testament to the reactionary year of 1968. As a student at the then Guildford School of Art, Walmsley documented the student-led sit-in, which lasted from the 5th of June to the 29th of July – making it the longest ever at a UK establishment. Writer and curator, and editor of nineteensixtyeight, Elizabeth Breiner presents Walmsley’s 1968 protest images, and discusses the country's history of student protests.

Students talk outside the canteen during the sit-in at Guildford School of Art, June 1968

"The sit-in happened because ‘they’ wouldn’t listen to the opinions of others,” British photographer John Walmsley wrote me, when I asked him if this spring’s university strikes resonated with his lived – and photographed – experience of the historically significant but oft-forgotten 1968 Guildford School of Art sit-in, the longest ever student occupation in UK history. “If ‘they’ won’t listen, what options do people have to persuade them of their errors? If you try all the proper channels and realise the decision was probably made months ago and we’re all just going through the motions, you’re going to be mightily pissed off.”

“If ‘they’ won’t listen, what options do people have to persuade them of their errors?”

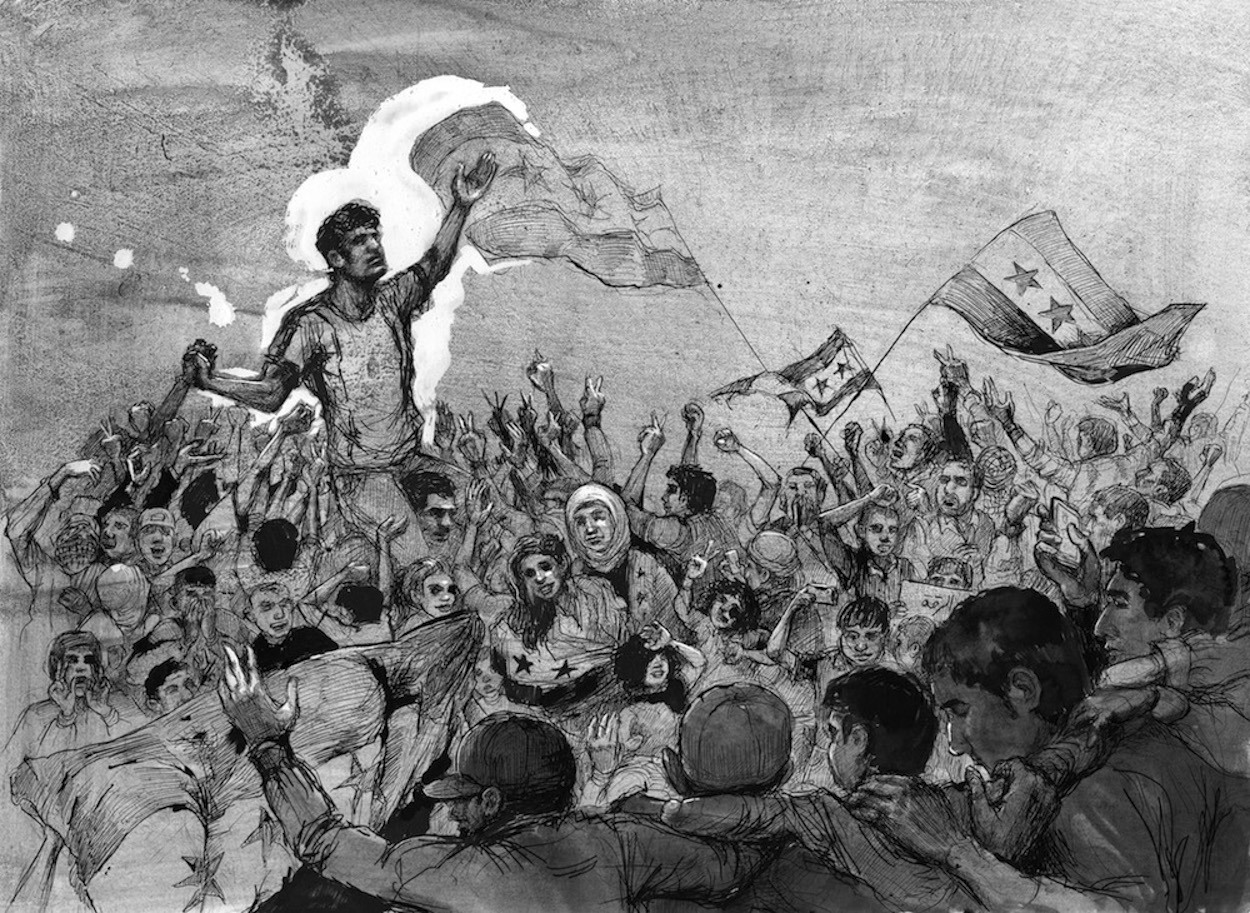

This May marks the 50-year anniversary of the Guildford School of Art sit-in, which can hardly be mentioned without acknowledging the concurrent, widespread, youth-driven demonstrations of the same year that shook cities around the globe from Belgrade to Berlin.

Inspired in part by the actions across the channel of the Parisian student protesters, the British student protests of the late 60s were nevertheless distinct in that student representation was a prime motive. In Paris, by contrast, the student demonstrations began as a call for educational reform, but quickly grew into a vast national movement — first against capitalism, consumerism and the hierarchical, autocratic nature of French society, and subsequently against the poor wages and working conditions of the working class. In the U.S., the student movement was chiefly sparked by civil rights disputes and opposition to the Vietnam War, causes that resonated powerfully in the UK and stoked the fire of rebellion but were not the causes célèbres.

Students working on correspondence and banners during the sit-in at Guildford School of Art

Moreover, though the London School of Economics riots are some of the best remembered, there was also a significant concentration of radical activity across the country’s art and design schools (including Goldsmith College of Art, Camberwell, St. Martin’s, and Brighton School of Art), the quality of which had long been a source of pride in the UK. Many of these schools were still operating largely as trade schools, and had significant numbers of working class students for whom access to proper resources and degree qualifications were essential to their future livelihoods. Thus what began as a 24-hour teach-in at Hornsey College of Art in May 1968 evolved into a six-week occupation — with a parallel occupation taking place at Guildford School of Art in Surrey — setting off a radical movement that spread to art schools around the UK and opened up a nationwide discussion about allocation of institutional funds, student influence on policy-making, and the future of arts education.

By 1968, as what critic Sean O’Hagan described as “a youthful desire to rebel against all that was outmoded, rigid and authoritarian” sparked movements around the world, students at Guildford decided they were fed up with the declining quality of the instruction and resources at the college and their inability to do anything about it. Spurred to action by rumours of department closures and a possible merger with Farnham School of Art, in late spring of that year representatives from the student body attempted to communicate these concerns, first to their student union leaders and subsequently to the school’s governing bodies. Their requests for an open dialogue denied, the students voted to stage a sit-in shortly thereafter; so commenced their occupation of the Guildford canteen, which would become their primary hub over the next eight weeks.

Students typically slept wherever they could during the sit-in

Students talking things through on the grounds of Guildford School of Art with Sociology tutor Mike Steadman during the sit-in

One of their first acts was to compose a letter detailing their demands to the school’s principal, Tom Arnold, who had been hired just three years before to try to revive the institution’s credibility and bring it back in line with industry standards. Arnold’s refusal to engage only hardened the students’ resolve, and in the ensuing days, various administrators and representatives from the Surrey City Council (SCC), who ran the school, visited in an attempt to persuade them to call off the sit-in to no avail. Tensions quickly escalated as, in an attempt to regain some leverage, the Board of Governors of SCC began threatening students and those faculty members that had supported them, withdrawing student grants, issuing writs for possession of the building, and suspending staff (a less corrosive precursor to eventual sacking). Ironically, according to Walmsley, these sacked instructors – most from the school’s Complementary Studies department – were the same few who students had rated as excellent, and many went on to become quite prominent in their fields.

Having joined the students, the security guards sent in by SCC are interviewed by local press during the sit-in

Despite their best efforts to publicly smear the participants of the Guildford occupation, making the students out to be dangerous criminals and disparaging the faculty members who supported them, the SCC governors were looking increasingly foolish. With the students showing no sign of backing down, SCC installed security guards armed with truncheons at the school with an eye to eventually ousting the student occupiers, by force if necessary. But it was only a matter of days before the guards had resigned from their stations and joined forces with the students after quickly realizing that the peaceful, articulate occupiers holding meetings, making signs, cooking, and cleaning were a far cry from the violent offenders they had been warned about by the board.

“It was only a matter of days before the guards had resigned from their stations and joined forces with the students.”

Students hang banners during the sit-in

By the end of June, SCC had officially closed the school with the students still inside it, cutting off the electricity, which did little but make the students – quite content to make do with candles and emergency kerosene lanterns – more angry and determined. Equally furious, the SCC Board of Governors applied unsuccessfully to the High Court for an order to evict the students (and jail them if they refused to comply), which, as one former student put it, not only woke the students up to the seriousness of the situation, but also to “how seriously they were taking it – that they were prepared to take legal action against their own students rather than talk to us.”

By the time the GSA students officially vacated the school at the end of July, after eight full weeks of occupation, SCC’s vilifying tactics were wearing thin and its public image had begun to unravel. Particularly damning was a letter that had been published in The Times backing the students, signed by various prominent academics and artists including David Hockney. Still, despite popular support for the students’ objectives and numerous calls for a public inquiry into the school, it took three years of political pressure and further sit-ins before a public inquiry took place and dismissed staff members were reinstated. As Walmsley put it, “The governors never did listen but, since then, schools, colleges and universities have had students on their boards” – representation hard-won.

After the sit-in at Guildford School of Art the previous year, students from Guildford and Hornsey Schools of Art march through London by to a rally in Hyde Park, May 1968

After the sit-in at Guildford School of Art, a demonstration of students from Guildford & Hornsey Art Schools and London nurses took place in Trafalgar Square, October 1968

As detailed very simply in one student leaflet advertising a June ‘talk-out’ event in Guildford, the essential demands of the occupation had been:

REINSTATE the dismissed teachers

IMPLEMENT the House of Commons Select Committee Report

REFORM in consultation with students

RETHINK the art education system

In the autumn term after the sit-in ended, students were still fighting for change and the re-instatement of the sacked staff. November 1968

But what the students ultimately found themselves protesting above all else was the board and other higher-ups’ complete unwillingness to communicate. Repeatedly resorting to backhanded legal action or the threat of force, the school’s governing bodies had shown a total disregard for creating even the pretense of dialogue. This assumption that those at the bottom of the pyramid should unquestioningly accept what was handed down to them from on high paralleled the wider concerns over class inequality and political disenfranchisement brewing in Britain and abroad.

“For the 71-year-old Walmsley, what might appear as minor manifestations of the ‘us’ and ‘them’ divide tend to be symptoms of a larger state of disorder”

For the 71-year-old Walmsley, who over his career capturing and working in radical institutions – and successfully pursuing claims against several government departments for infringing on his copyright – has become something of an unofficial and unlikely expert in the art of protest, what might appear as minor manifestations of the ‘us’ and ‘them’ divide tend to be symptoms of a larger state of disorder. In his words, “It’s all linked.”

While his sons now pay over £9,000 per year to attend university, thanks to the country-wide tuition hikes of 2011, “the bankers make off with our pensions and savings. For the most part, they’ve kept it all. Some poor parent, trying to keep the wolf from their family’s door, does some minor shoplifting and is fined or imprisoned. [The] whole thing is out of balance and the gap between rich and poor is widening.” And despite accounting for 5% of the British economy, nearly £80bn, arts services and education account for less than 0.3% of the government budget, with creative arts subjects in secondary schools increasingly cut and sidelined to prioritize the ‘core’ subjects.

Students continued to picket and fight for the re-instatement of the sacked staff in the autumn term after the sit-in. Here, police are called in. November 1968

The sacked staff from Guildford and Hornsey Schools of Art held an exhibition of their work at the Institute of Watercolour Painters Gallery in Piccadilly, London to raise awareness and funds. John Lennon & Yoko Ono came to show support. While in attendance, they distributed sheets of A4 paper on which was written: "Fold this 9 times.” No one succeeded. December 1968

As in the case of Guildford School of Art, which nearly closed down entirely as a result of the public condemnation of SCC provoked by the sit-in; and as with the recent wave of university strikes, which saw 65 institutions cancel hundreds of hours of classes and utterly derail the upcoming exam period, sometimes the deliberate destabilization of existing structures until their very functionality is under threat can be the only way for those at the bottom who have found themselves voiceless to regain a place at the table.

“Personally,” Walmsley told me, “I’ve never agreed that you need to be a bastard to succeed in business. [A] much better approach is to respect people and things will go better... This is particularly true in education where, to my mind, business has no place at all.”

With young people now facing what he describes as “an impossible future” of debt and low employment, they are in some ways in a position best suited to protest: with simultaneously everything and nothing to lose. And though structural changes are rarely immediate, widespread exposure, particularly nowadays, can insinuate vital concerns back into the public consciousness and force them onto the political agenda. During the period of the strike alone, the University and College Union recruited over 4,000 new members – future capital for greater disruption; the striking staff succeeded in getting the proposed pension cuts dropped; and perhaps most importantly, the strike incited widespread criticism of UK universities’ priorities and management structure. Whether sitting in or walking out, success must be measured in the ability of the dispossessed to change the conversation and increase their power to direct it. And when you’re failing to be heard, follow Walmsley’s advice to do what most people won’t: “Stand up and complain … you can never expect something to change or improve if you don’t."

All images courtesy of John Walmsley and nineteensixtyeight / John Walmsley is a British documentary photographer based in England and represented by nineteensixtyeight. His work is held in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery, London, and the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, among others. With thanks to Elizabeth Breiner

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.