Beauty is Still in the Streets

50 years on from the French uprisings of May 1968, gallerist Steve Lazarides displays his personal collection of posters by the Atelier Populaire, and explains what gives these political prints their power

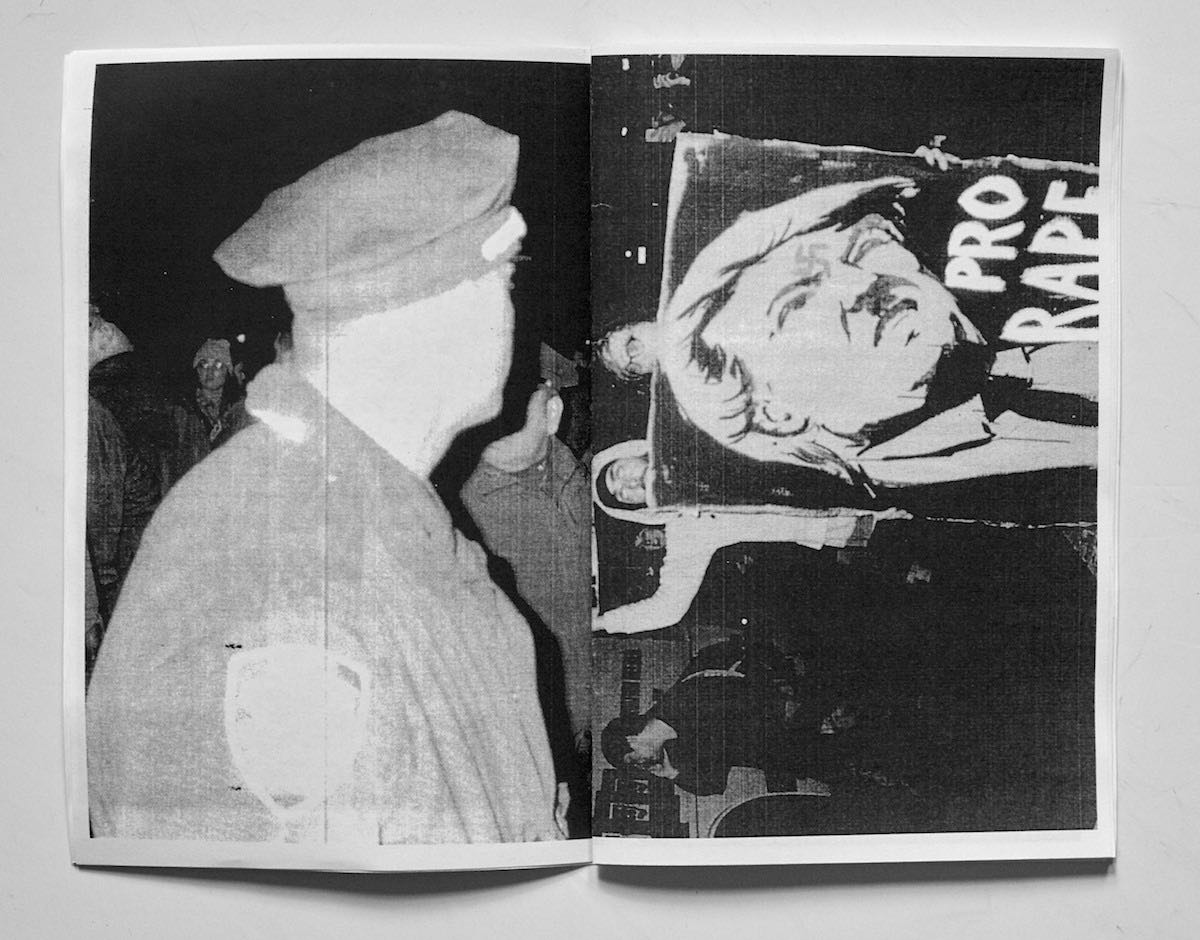

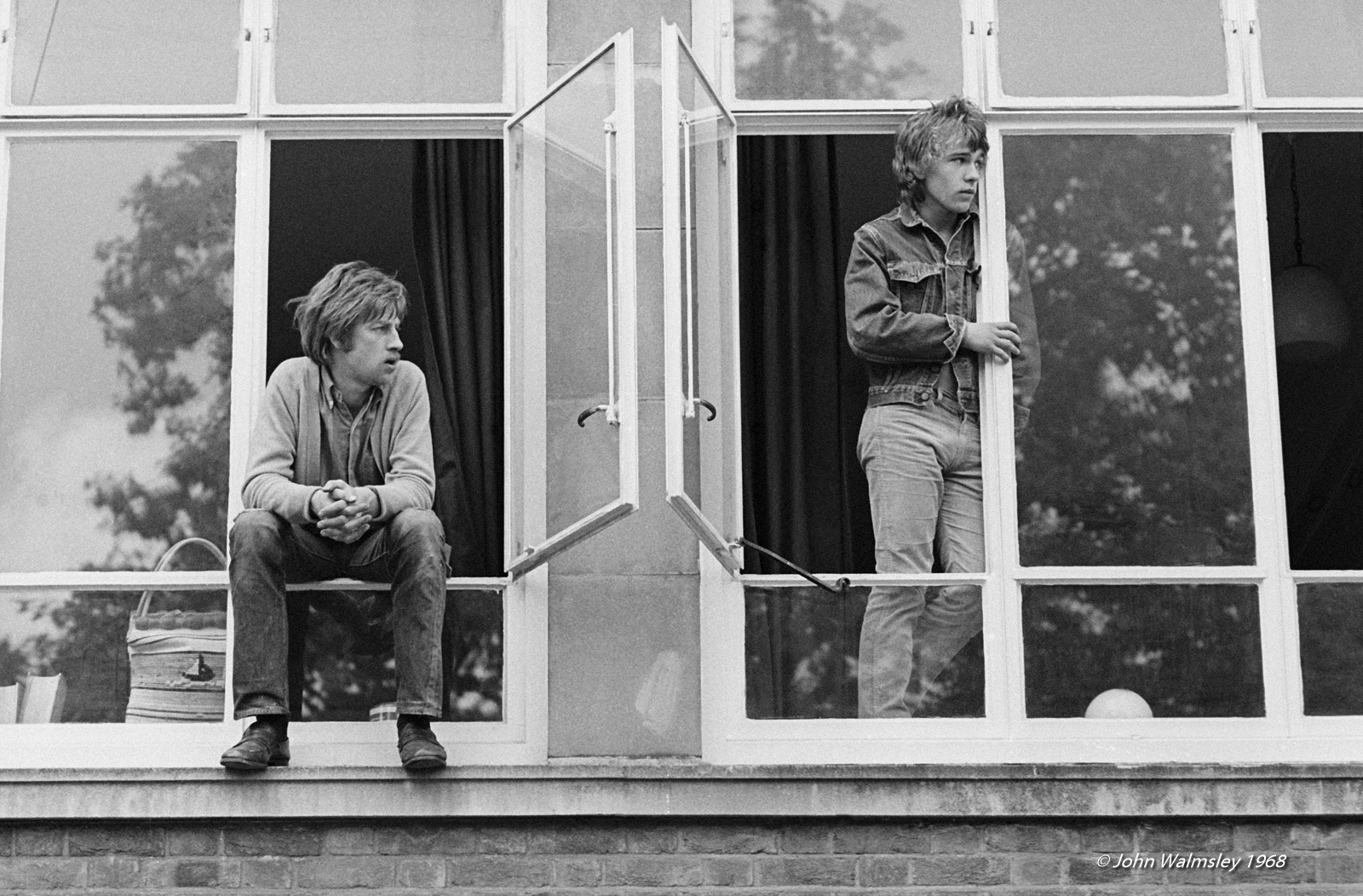

May 2018 marked 50 years since mai soixante-huit – the wave of uprisings, demonstrations and revolutions that rocked Paris in 1968, when thousands of youths and millions of workers took to the streets to shut down the (take your pick) petty right-wing authoritarian government of Charles de Gaulle, consumerist culture, US imperialism, capitalism, racism and traditional sexual morality. The protests had varying degrees of success, but in the five decades since, those turbulent months have etched themselves into our popular vision of protest: students in corduroy jackets and bandanas clambering over barricades; all-night lectures attended by steel workers and filmmakers; city walls that yelled “It Is Forbidden To Forbid”, “Beauty is in the Streets” and “Be Realistic: Demand the Impossible”; sexy people running in black and white; stark graphics depicting riot police as SS officers, plastered up on the streets every night.

“In the five decades since May 1968, those turbulent months have etched themselves into our popular vision of protest…”

Often, the searing boldness of these posters transcends their time – their language and their thin paper, produced by striking members of the newsprinters’ union on the cheap pulp that usually carried tabloids. The next day's posters were decided each evening by members of the Atelier Populaire, a group of anonymous designers, printers, and sloganeers. These political posters, radical in intent, hastily produced and communally created, would then be pasted around town under the cover of darkness, to be seen by millions of passersby before being either torn down, covered up, or washed away by the rain. Or, sometimes, quietly kept by Parisians who spotted their beauty, and wanted to have a little piece of history in the making.

These posters have found their way into the collections of institutions, museums and private galleries, and today, are part of our visual landscape – inspiration fodder for advertising executives and millionaire street artists as much as designers and activists. One gallerist, however, is keen to reboot their radicalism: in May 2018, Steve Lazarides, gallerist for globally renowned street artists such as JR, 3D, Invader and Banksy, put on a show of his private collection of Atelier Populaire posters, alongside a screenprinting workshop so visitors could make their own. Lazarides also invited Good Trouble along for the ride.

“This wasn’t aimed at the elite. If you suddenly used references that you need a degree to understand, it wouldn’t have worked.”

What about the Atelier Populaire speaks to our time?

Steve Lazarides: I love the fact that they wanted it to be completely anonymous. They didn't want anyone to know who the authors were, just the work. These posters would be voted on and then produced. It was a truly socialist movement! They were given paper by the newspaper union, which is why the prints were such a shocking quality – it's amazing any survived. From the workers to the students, everyone on the left were aligned, and they were just so prolific about putting stuff out there. There was just so many of them! The Paris riots were happening, so they were putting stuff out at great risk to themselves. It was very on-the-edge and close-to-the-bone stuff.

What’s the power of a poster?

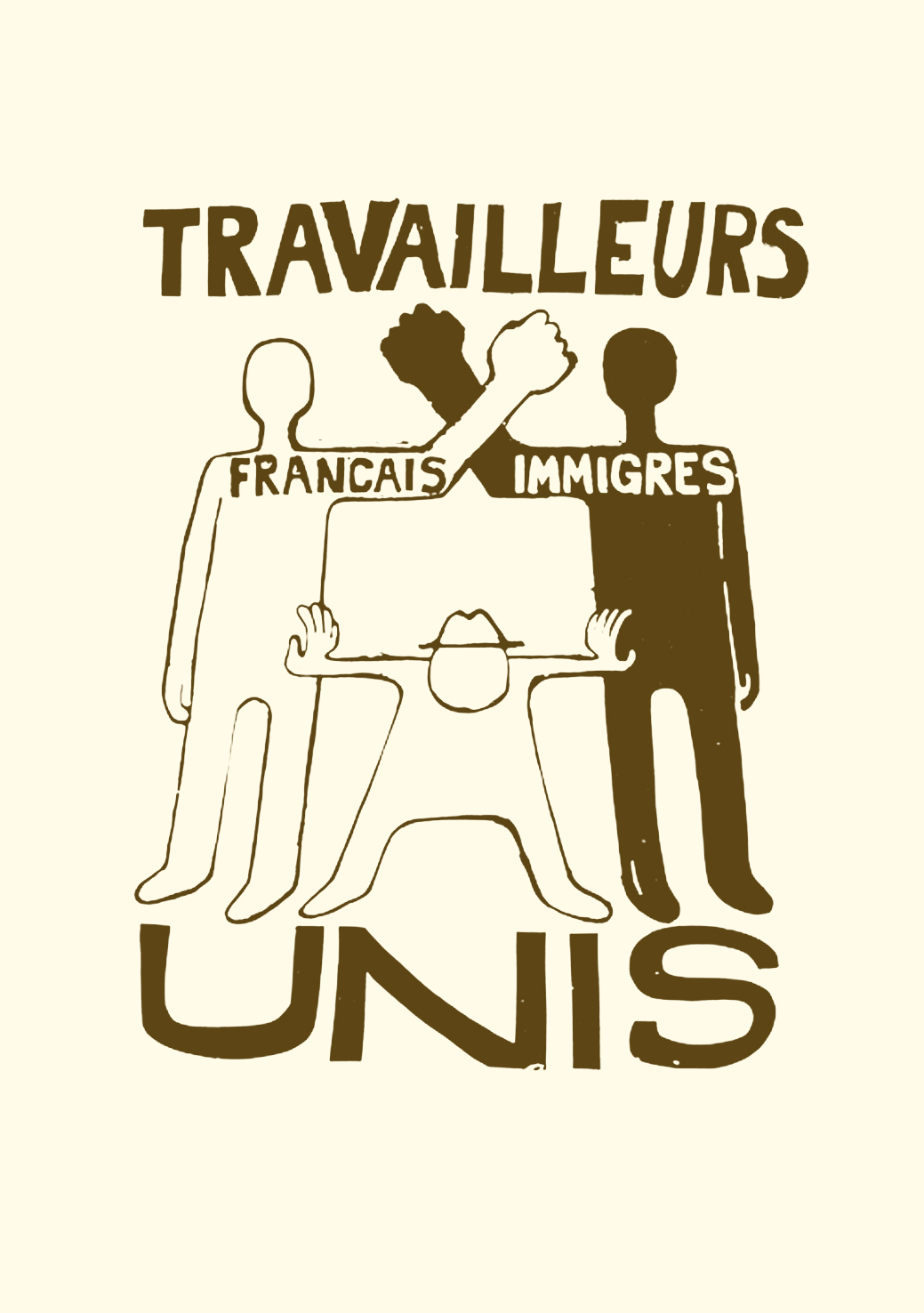

Even in today's internet and Instagram-friendly society, I still think posters have a place. If you look at Shepard Fairey's Hope poster, that helped elect a black man into the presidency of the United States. Posters still have a tremendous amount of power. You might not watch this TV show, or buy a newspaper, but we have to go outside, at which point you are confronted by all these posters. One of the reasons that they work so well is that they are unbelievably simplistic. It's a one-colour screen print, with one very simple graphic, and one simple message. If you walk down the street and you see a complicated image on a wall you walk past it, but this is something that is so visceral, so immediate, so angry and so in your face, you're stopping people in their tracks.

Can we talk about how they use images and words?

This is amazing, isn't it? “Vive la resistance of the proletariat.” Or this image of a head being screwed, or the immigrants and French workers uniting, even as a factory owner tries to pull them apart. I just love the aesthetic. I love the meaning of it. I like the simplicity of it. People get overly complicated sometimes, but this is aimed at the working class. This wasn't aimed at the elite. If you suddenly used references that you need a degree to understand, it wouldn't have worked. Something that's so clever is that they're using one sentence and an image to get their message across, and it's happening every day. This speed is so important, as is the fact that you can't avoid it because it's on the street.

Writer and editor based in Berlin.

![[What's-changed-].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5846f7493e00be622f3bfb1a/1529090238602-DIK0F8IFSGZCEFLTXQTO/%5BWhat%27s-changed-%5D.jpg)