'Rebellion is a damn good thing!': Harry Leslie Smith

As a child growing up in the slums of Yorkshire, Harry Leslie Smith was so poor that that his family dinner was often a bowl of broken cereal salvaged from the nearby Weetabix factory, eaten with water. There was not yet a National Health Service or any kind of social safety net, and with his father out of work, they were at the mercy of others. (Update Nov 28: We at Good Trouble were very saddened to hear of Harry’s death last night. He was a hero and inspiration to many, and will be missed. RIP.)

Now 95, Harry is a survivor of the Great Depression, a veteran of the Second World War (Royal Air Force) and a lifelong socialist who contends that the world is now facing its “most dangerous juncture since the 1930s”. At an age where most might be putting their feet up for a well-earned rest, he is busy owning racists and idiots on his ever-lively Twitter account, contributing articles and videos to the New Statesman, the Daily Mirror and the Guardian, and funding his speaking tours from his old-age pension and the royalty fees from his five books.

When I called him in Toronto (May 2018), where he lives for half the year, he was making final preparations for what he describes as his “last great challenge” – a crowdfunded tour of the world’s refugee hotspots, aiming to “document this preventable tragedy that may lead us to another war as gruesome as the one I helped fight against Hitler over 70 years ago”.

Harry, thanks for speaking to us. I’m thrilled we can feature you...

I’m thrilled I’m still alive! It’s been a tough year.

I understand you had pneumonia earlier this year. I’m glad you’ve returned to health. How are you doing?

You can’t keep an old bugger down, you know?

You were treated for bronchitis just one month after the NHS was founded in 1948. How does it feel to be saved again by the same service so many years later?

It was a miracle. Because nobody had ever given us anything, since I was born – no one in my class was entitled to a doctor or dentist or hospital. In that age, you just had to settle for anything you could find in nature. People can’t believe it today, and unfortunately they’re closing their eyes to the ructions in our present-day hospital service.

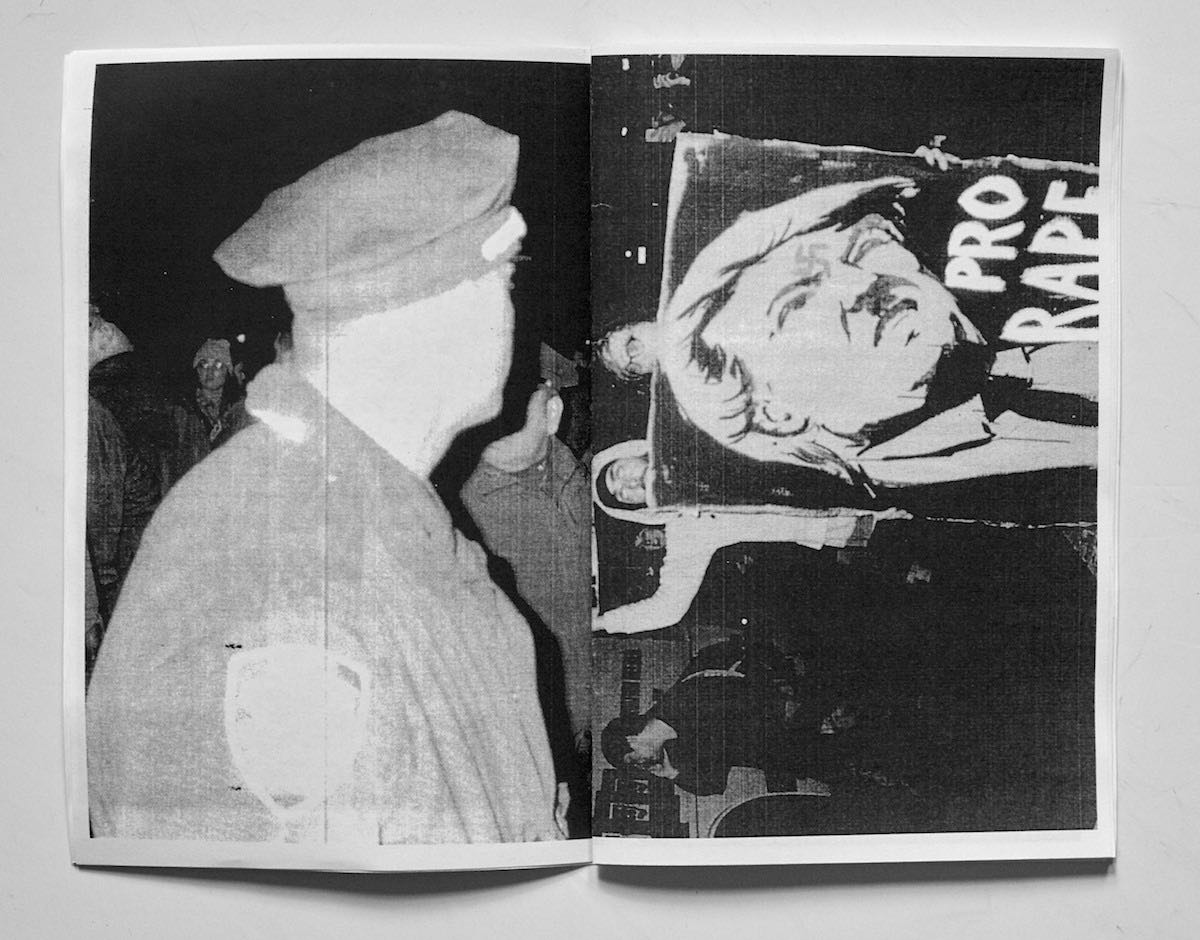

Harry at the ‘Jungle’ refugee camp in Calais, France

You’re in Canada at the moment. Where are you, and what are you doing?

I live half a year here, half in England. And soon, in what shall be my pièce de résistance, I’m going to visit all of the refugee camps around the world. I’m starting off in Québec, and then from there I will go to the States, then I’ll be off to Greece and up through the Balkans. After I’ve done the EU, I’ll be writing another book – what I feel could put some sort of resolution to all this business of infighting, about who’s going to supply this or that.

Why is it important to you to go on this huge trip to these refugee camps?

It’s important because we have to find out what all these other countries are going to do to at least place many of these people... and to regain the spirit of 1945. I watched the refugees flooding from the north to the south when I was in the Air Force. In Holland and Germany too, and it was a pitiful sight, believe me. But England never turned her back on refugees. She built places for them to stay, she made sure the kids went to school, and if anyone in England protested about it, they would just tell them to shut their gobs because you hadn’t seen anything yet. There’s going to be a hell of a lot more.

You’re in your mid-90s now. What gives you the motivation to keep on doing these things at an age when you would be easily forgiven for deciding to put your feet up?

“I started late because I didn’t get angry enough, early enough. It wasn’t until the 2008 banking crash, when people were robbed and no one got blamed for all that crime… I was 85 then! And when I read about it, I got so bloody mad. I was lying on the beach, relaxing in my retirement, in Portugal... and then I just went to work and did what I could.”

Remember, I started late because I didn’t get angry enough, early enough. It wasn’t until the 2008 banking crash, when people were robbed and no one got blamed for all that crime. They bailed out the banks but they didn’t do anything for the people who were robbed, because that is when they intro- duced austerity to the rest of the people, and it’s been in ever since. It was the people who paid for the banks, not sacking them and sending the people who ran the banks to jail.

So, that was the moment you decided to become an activist?

I was 85 then! And when I read about it, I got so bloody mad. I was lying on the beach, relaxing in my retirement, in Portugal... and then I just went to work and did what I could – starting to write, and luckily found a publisher for my most famous book, Harry’s Last Stand, which has been a tremendous seller, and still is.

I guess you’re going to be on your refugee tour when Trump visits the UK this summer. But if you were in the UK, would you join the protests?

I most certainly would, but I don’t think he’ll find that he’ll get too big a reception. I know, when a country changes government, there’s always turmoil. But when you get someone put into a position like Trump, it shocks most people. So far in his reign, all he’s been doing is hiring and firing until... He’s creating a game. He’s creating chaos.

Well, hiring and firing was the reality TV show he came from.

Yes. I hate to say it, because I love the US, I’ve spent many happy times there, but we were all floored when he started trying to say, “These people can’t come in, and those people can’t come in...” It makes you think the whole world has gone crazy.

Let’s talk about Britain for a little bit. After the results of the Brexit referendum, there’s a lot of nationalism, xenophobia, racism. I wanted to ask – in your experience, do you think this has always been part of who we are as a country, or is it something truly new and dangerous?

It’s new and dangerous, for sure. It’s a certain gang of people in England who want to change society... I sometimes despair for it.

It’s been one year since the Grenfell tower fire in west London. How much has the housing situation changed since you grew up poor?

After the war, we made sure we were going to have a government by the people and for the people, and we succeeded for a while. And before we got into our power, there were individual men who had fought in the First World War providing shelters for returning soldiers. I was a late leaver from the Air Force – I didn’t get out until 1948, because I married a German girl over there. I was so happy and hoping I could stay in Hamburg, actually. Because it was a hell of a sight better to live there than in England.

Pages from Good Trouble ‘Issue 22’

You survived the war, you lived through the Great Depression... What words of advice would you have for a younger generation at this time, from someone who has been through several major crises in his lifetime?

Well, General Sherman once said: “War is hell. Stay out of it.”

Right.

And believe me, it’s no cup of tea. You’re dead, you’re dead and that’s your life, so don’t get involved! No matter what governments tell you, war does not solve anything. It’s debate and discussion, and I’m not sure you would get it from Trump. Maybe he would pass a law which forces you to go. But I think if everyone stood up and said, “We’re not going to go to war, because war involves another country, and that country involves another country, and so on...” It spreads around the world... This time, it would be armageddon, in my opinion.

Like during the Vietnam war, when people refused to go and burned their draft cards in the streets?

That’s right! That’s right. People don’t realise what power they have, if they put their backs into it and have an opinion of what’s right and what’s wrong.

But how does the scale of what we’re facing now compare? Is it as serious as other moments you’ve lived through?

What myself and all the other soldiers, including the Americans and everyone else who fought in the war I fought in... They would think that was a picnic to what we would get if a war erupted in this day and age. There are too many ghastly weapons at hand which will eliminate the world, in my opinion. And we will wind up where we started – living in caves or some derelict place in the islands, hunting for food like our ancestors.

You’ve got almost 200,000 followers on Twitter. What have you learned from using it?

Social media is how I can connect with more people. It’s very handy, it’s a good way to get a large number of people listening, especially young people. Unfortu- nately, many have never had enough money to go to university, never had enough money to feel free. And they’re stuck in a rut where they can’t happily afford to have a beer at a pub. That is real life for them, and they will easily rebel.

“Rebellion, while I’m on it, is a damn good thing! They have to get together in a group and they have to march on the Houses of Parliament and the White House, whatever party is running them, and let them know they’re not going to put up with the bullshit the governments are handing out.”

And rebellion, while I’m on it, is a damn good thing! They have to get together in a group and they have to march on the Houses of Parliament and the White House, whatever party is running them, and let them know they’re not going to put up with the bullshit the governments are handing out. Because it’s all a bloody lie, and they can change it if they will, by making sure all the people in the upper echelon of our countries, who don’t pay enough taxes, make sure they are declaring what they made!

On that note of rebellion, Good Trouble takes its name from a quote by the American congressman and civil-rights hero John Lewis, who says, “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have a moral obligation to go out and get into trouble. Good trouble.” What do you think about that?

I think it is a fantastic quote. It’s excellent, and like I said before, people have got to start pulling some muscle behind their protests. They have to start showing governments they’re not going to sit quietly and do nothing. I am disgusted when I go to England and look down city streets and see hundreds of their citizens lying on the side of the street with their hands out, where they slept. How can a government feel it’s doing its job?

Indeed. Thanks, Harry. I don’t want to keep you too long, so one last question. Ultimately, what gives you reasons to be hopeful for the future?

I’ve always been optimistic, actually. And I’ve always been a worker. I’ve never had a job where I could sit down and say, that’s it, I’m finished now. I work all day long. I sold carpets in a carpet store in Toronto. I just felt that, somehow or other, we should always be doing something that would put us into a category, even if dead, where people would look back and say, now, there was a man.

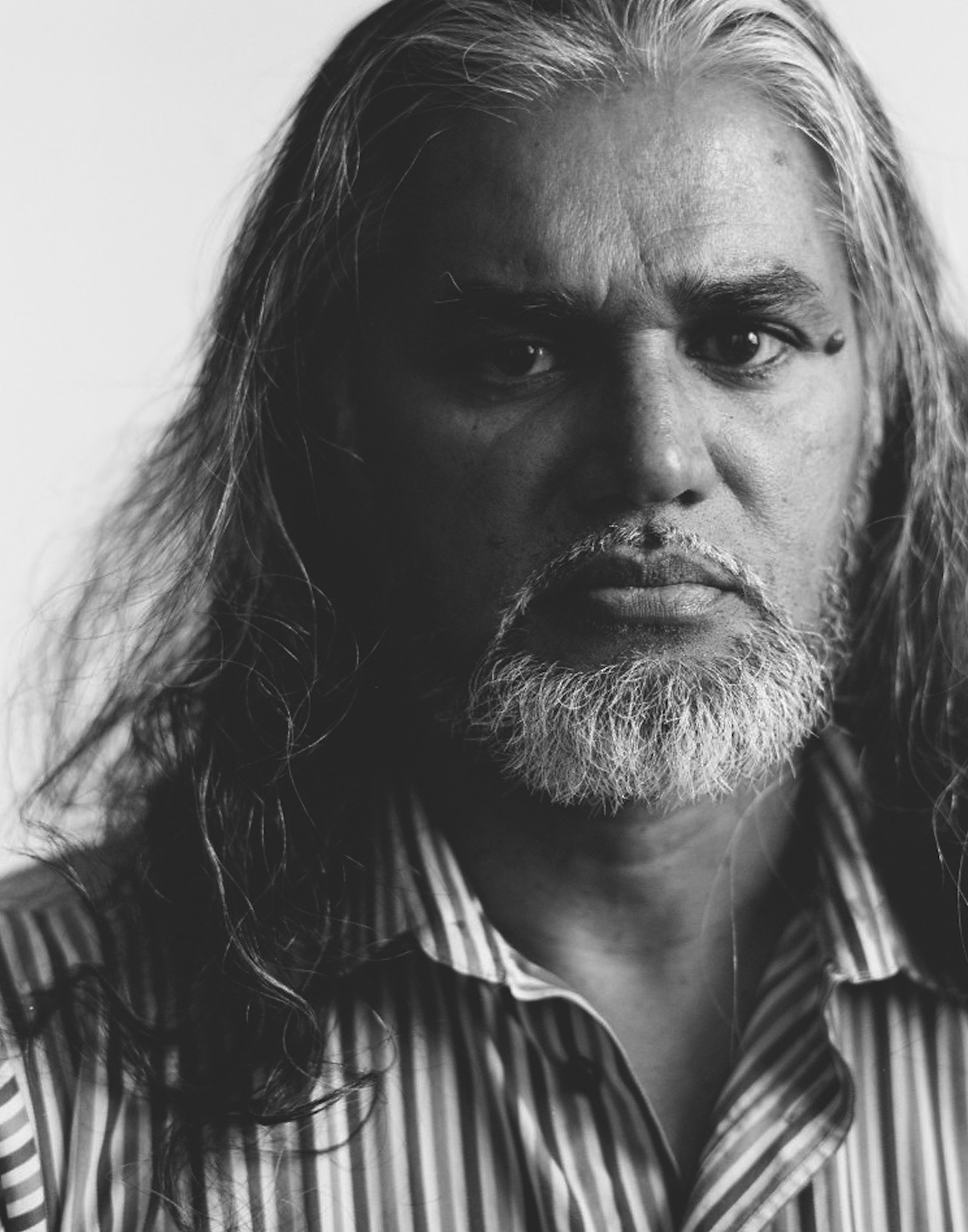

Main photograph of Harry at home in Canada by Alana Derksen for Good Trouble.

Don’t Let My Past Be Your Future is published by Little Brown

ACTIONS

Support Harry’s fundraiser for the Harry’s Last Stand Refugee Tour

Writer, editor and consultant based in London /New York