Drunken Baker: Barney Farmer

The sun is shining and Good Trouble is ensconced in a London pub beer garden with Barney Farmer, a writer of rare talent whose work such as Drunken Bakers and The Male Online, published in the UK’s long-running, notorious Viz adult comic, reveal him as an astute observer of the rot on the vine currently so rampant in society.

As the hours flow by over a pie and a pint (OK, more than one), Farmer explains how the motivation to create his world-weary characters, who have had the stuffing knocked out of them by the vicissitudes of modern life, can come from the most mundane of places.

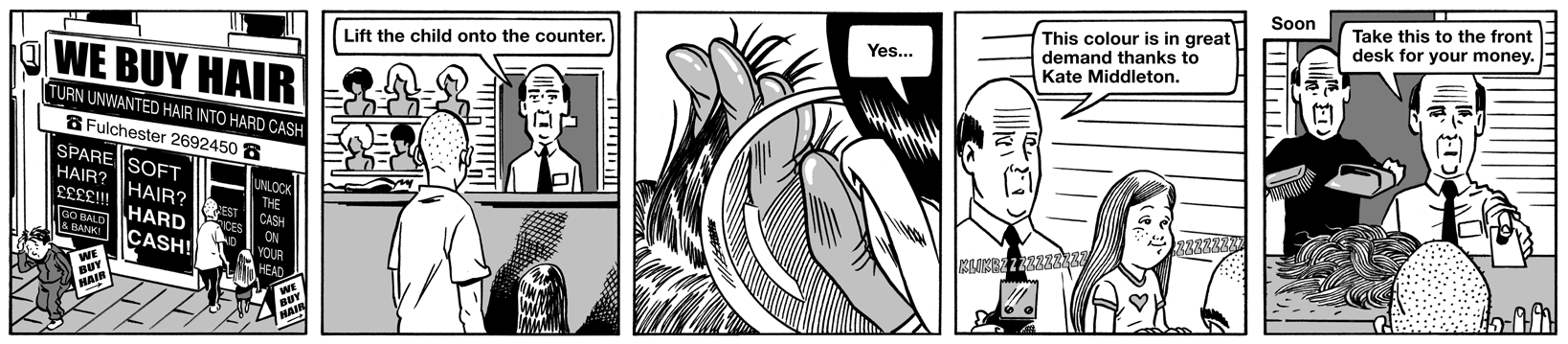

“The story of Britain can be told many ways, but it can be best told on its high street. It’s now a greasy takeaway every few hundred yards, and We Buy Gold shops, We Buy Clothes... It’s the high street telling you what’s actually going on in Britain – that it’s a space to be inhabited as long as it’s profitable to do so, then move on.”

“The story of Britain can be told many ways, but it can be (best) told on its high street,” he says. “It’s now a greasy takeaway every few hundred yards, and We Buy Gold shops, We Buy Clothes... It’s the high street telling you what’s actually going on in Britain – it’s a space to be inhabited, for a time, as long as it’s profitable to do so, then move on.”

He cites one of Britain’s greatest writers and chroniclers of social change as an unlikely influence on his work. “Charles Dickens, writing at a time when the written word was pretty much the summit of home entertainment, had phenomenal power. And it’s fairly obvious his influence in the late 19th, and into the 20th, century was the equal of any politician of that day.”

In his comics, usually illustrated by his trusted partner Lee Healey, Farmer is a scabrous and articulate voice for the left-behind – those people who are subsisting on benefits but are still quizzed on a daily basis by an unrelentingly hostile state, or struggling in dying industries such as baking, still trying to pretend, somehow, that everything is alright.

––

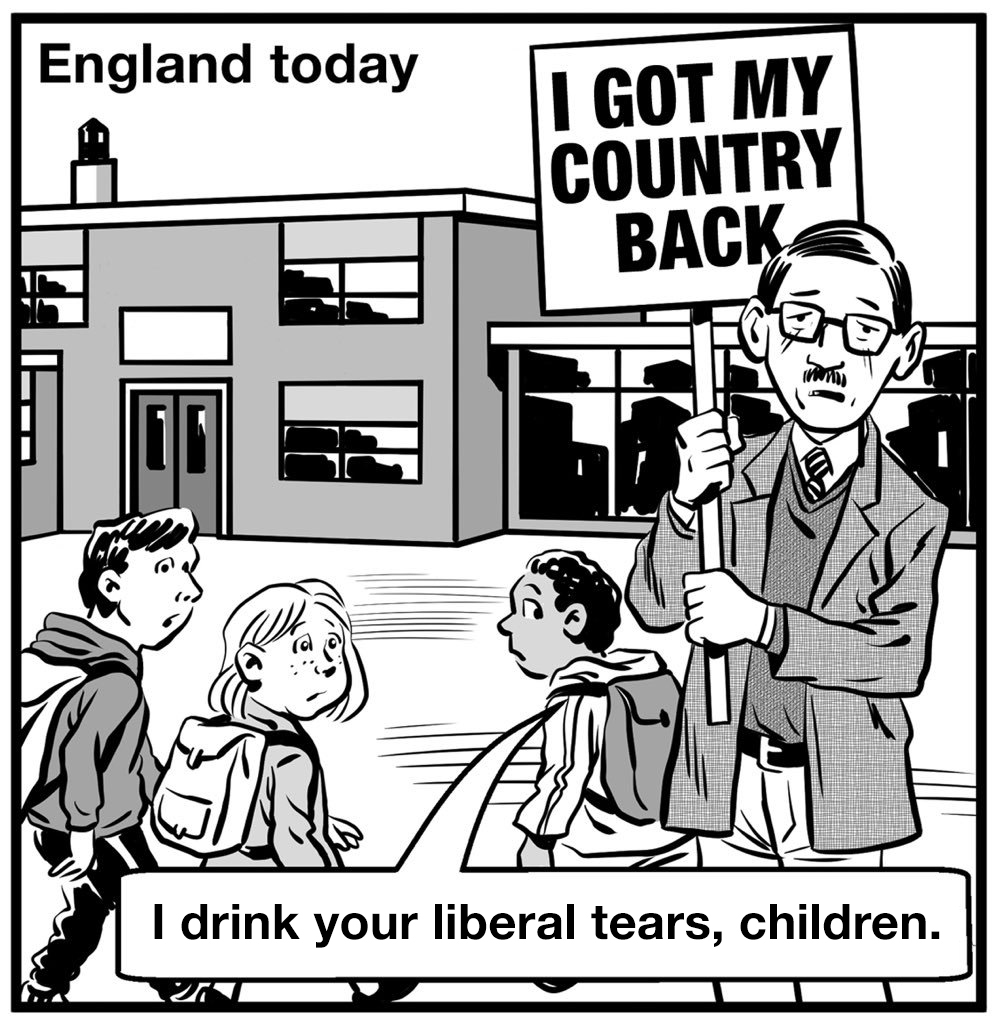

These are dangerous times. Reactionary voices gain such play across social media that you need to be running before you’ve put your boots on to counter their accusations that it’s all the fault of the immigrants, the foreigners, the “other”. In the UK, we have been experiencing nascent culture wars over the last few years, and since before the 2016 Brexit vote to leave the EU.

Mercifully, many figures have emerged in the British social media space who have led the fight against the new wave of hard-right hostiles. And foremost among those is Farmer, from Lancashire in the north of England, whose blend of caustic wit, compassion and empathy has marked him out as one of our champions in the ongoing fight to retain our common humanity.

“They don’t like it up ‘em,” he says of Leavers (people who voted for the UK to leave the EU), but the comment could easily apply to any of the reactionary groups at work today. “They talk about free speech, but they’re tremendously pious. That’s the lethal combination – giving but not taking, it’s the mentality of the bully.”

Through The Male Online, self-published on Farmer’s Twitter feed, Farmer lampoons the Little Englander keyboard warriors who embody the spirit of the country’s middle-market tabloid the Daily Mail, pushing for the hardest of Brexits and railing against every aspect of multicultural modern Britain.

Farmer’s loathsome cartoon character, a cultural product of our times, is also obsessed with the salaciousness of the Daily Mail website’s infamous “sidebar of shame”, with its leering pictures of young women “old beyond their years”, to the extent that his internet time is spent with his trousers halfway down his thighs (“It’s my hernia, Beryl!” he explains to his long-suffering wife); Farmer’s caricature neatly skewers the abject hypocrisy of this depressingly large group of people.

In his other work, Farmer focuses on the appalling indignities that those on the lowest rung of society’s ladder are forced to endureto maintain the basic levels of survival – his targets are the pawn shops and bookmakers that prey on the poor, and the benefits agencies that enforce degrading interrogations to determine people’s level of poverty. If you had doubts about how low this could go, Farmer cites the case of a woman applying for sickness benefit for her depression, who was asked by the government agency examining her claim: “Can you tell me why you haven’t killed yourself yet?”

It’s with the Drunken Bakers strip, which first appeared in 2002, that Farmer and Healey present the truest glimpse of what Britain looks like. It’s become lazy shorthand to say it is reminiscent of the work of Samuel Beckett, but it’s a fair description. In every iteration of the story, we follow two (unnamed) middle-aged bakers who (drunkenly) go about their day’s business, not managing to bake any cakes and embarking on journeys down rabbit holes into a past where the future was still wide open and their destinies were under their own control. Nothing ever changes – the bakers stay drunk, the cakes remain unbaked.

It’s bleak stuff, but it articulates the current hopelessness of the lower echelon of British society – the people who once serviced the manufacturing base that made Britain the heart of the industrial revolution.

“I was born and raised in a little industrial town,” says Farmer. “All the industry was gone. Lancashire had a very particular experience – a lot of the things that happened in the rest of Britain in the 1970s and 80s had already happened in Lancashire. A lot of it had gone by the time I came along, because the cotton industry, which was basically sustained by keeping a boot on the neck on India, it was gone.”

“Boredom is a great fire up your arse. If you get bored enough, there’s just a chance you might do something to entertain yourself.”

Growing up in a region defined by a dying industry, Farmer left school at 15 and worked “in dead-end jobs” for a while. “Boredom is a great fire up your arse. If you get bored enough, there’s just a chance you might do something to entertain yourself.”

For Farmer, that eventually led to creating comics. The renaissance of that industry in the 1980s led by Viz saw him secure work at a slew of copycat titles, along the way meeting his long-term collaborator, artist Healey.

“I was a cartoonist, but I was terrible,” says Farmer. “Editors would find me cartoonists to work with but I’d never quite click with them. As soon as I started working with Lee and saw how he drew, it suddenly became a lot easier to write. We had a stack of work we had done for other places, and we sent a telephone directory of strips to Viz – I’d never sent anything before, as I always assumed they had everything covered. They plucked Bakers out of that big wad and said, ‘We’ll have this one.’ That was the first one.”

Since 2002, Drunken Bakers has been a stalwart of Viz: it has chronicled the demise of traditional services and society as authentically as any economic study of the state of the nation. For Farmer, bakeries were a barometer of British society: “There would be a town full of terraced houses, and at the end of every street there would be a baker. So a town of 50,000 people, it probably had a bakery for every hundred people.

“Family-run bakers in Preston have been there for generations. All you need is one poor town, and it gets two Greggs (a national chain), and then that’s four or five bakeries nailed... Supermarket bread on top of that. They’ve come under attack from multiple angles. It was one of the things that dawned on me, that bread was a metaphor.

“We do have a culture war. We have wars across every debate, and it’s more or less the same sides. People are at war over absolutely everything. Up until a few years ago, I was quite an angry participant and would often get involved in slanging matches. Time has mellowed me slightly. I try to engage people, who don’t necessarily share my politics. In a polite way.”

Farmer’s acceptance spreads to his behaviour on social media: “I’m followed by quite a lot of people whose politics I find reprehensible. I think it’s good to follow a representative sample of people you don’t agree with. I wouldn’t want to exclude them altogether, not least because about 25% of The Male Online strips I’ve done have derived from reactions I’ve had. Twitter’s a great resource, a good place to learn how what’s going on in the world is affecting a certain selection of people.”

It’s good being a satirist, right? Taking the piss out of everyone? “I didn’t set out as a satirist,” he says. “I wanted to write about things that were real, not necessarily political things. It was more the things that Viz writes about – it was archetypes, things you see in the real world, shops, and the man you see in the park. That’s what I set out writing about, then everything changed about me. The knock-about press has failed, it’s become part of the absurdity – it’s become a driver of the absurdity. The fourth estate has a very serious responsibility.”

In many ways, life caught up with Farmer, rather than him seeking to make waves: “Brexit is a disaster. I laughed when Trump got in because it’s obviously so absurd. I didn’t laugh the morning after the Brexit referendum. It was equally absurd, but I’m right in the middle of it!”

The thing with Brexit is we see ourselves returning to the glory days of Empire, he says: “We’ve gone past the imperial hangover, we’ve woken up, and we’re drinking again. We’re pissed again!”

Words by Seth Jacobson / Photography by Stephen ‘L-L, Hard as Hell, Rock the Bells’ Ledger-Lomas

Drunken Baker by Barney Farmer is published by Wrecking Ball Press.

All art by Lee Healey © Viz

Article taken from Good Trouble Issue 22, available here

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.