Radical Energy: Penny Slinger

Rejected by nuns and second-wave feminists alike, radical artist Penelope Slinger turned to collage to remake her own reality. Tess Gruenberg talks to Penny about the transformational art of collage, the divine feminine, and how to become your own muse

When sick as a child, Penelope Slinger would kill time by making collages. Learning young that creativity was a good remedy for boredom led to a six-decade career of creating radical new realities out of old fragments.

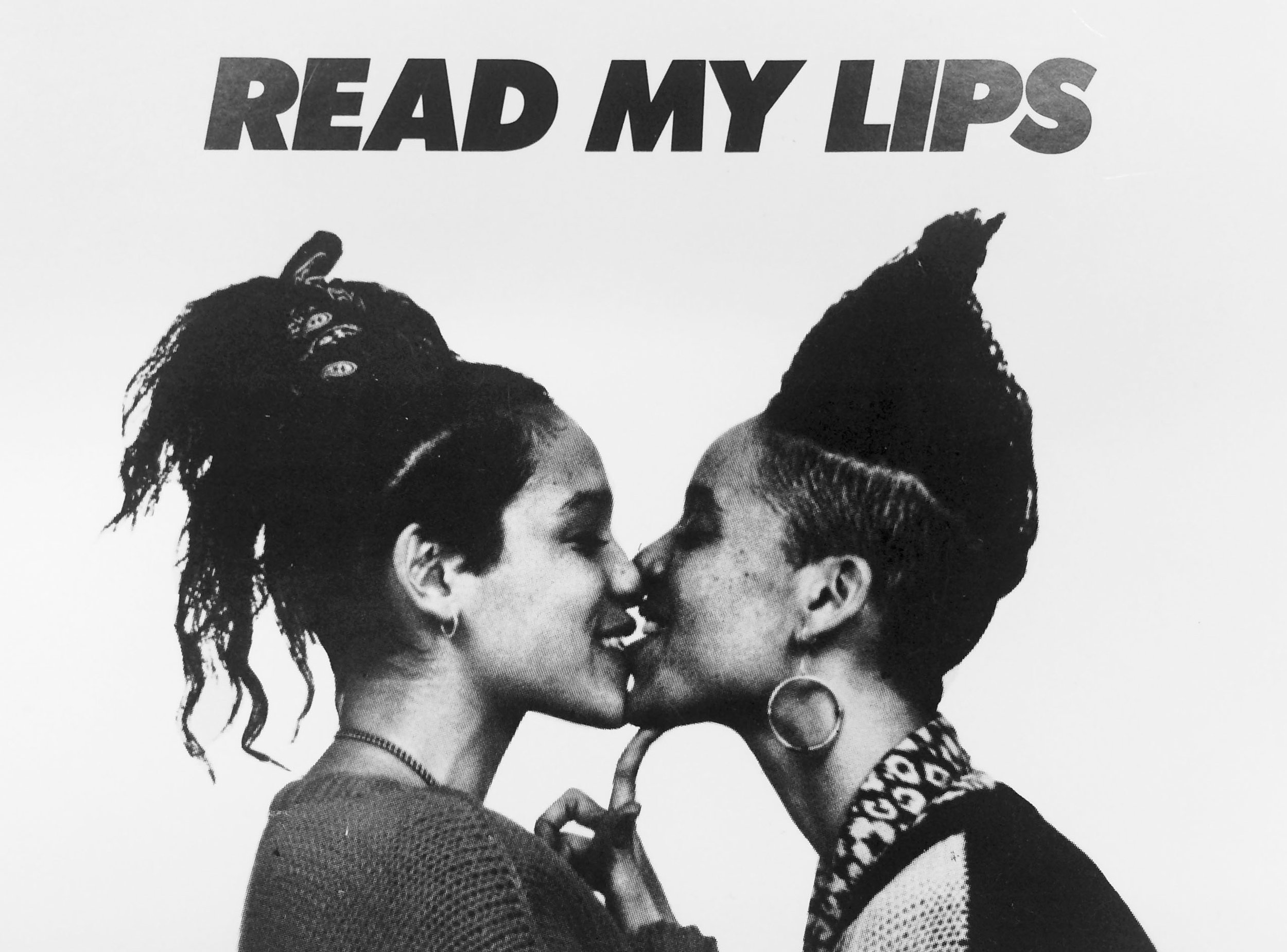

Slinger first shocked the art world in 1969 with the publication of 50% The Visible Woman – a thesis-turned-book of photographic collages that subverted the tools of male surrealism by baring her own body as a detailed object of the feminine psyche. By objectifying her own self, she haunted the silos of second-wave feminists and conservative cookie-cutters alike.

Throughout the 70s, she continued to challenge the rigid paradigms of creativity by fearlessly playing both roles of artist and muse, while working in multiple media – film, theatre and sculpture – with the likes of experimental artists Jane Arden and her longtime partner Peter Whitehead. Pushing the boundaries of eros was the name of the game.

In 1980, Slinger moved to the Caribbean and sought for many years to create without the pressures of an art world hell bent on commodifying all acts of resistance; it was only in 2009 that she was reintroduced into the art scene after her inclusion in the Angels of Anarchy exhibition at Manchester Art Museum.

Her mission as an artist remains strong: to uplift the divine feminine and equalise a spiritual balance long out of whack. With Slinger’s recent set design for Dior’s FW19 house couture show and the release of Out of the Shadows, a documentary telling the story of her life and work, it is obvious now that her art was prophetic – a future-feminism-now-present, where the feminine and masculine transcend the biological, existing as divine energies in constant creative play.

What was your first encounter with collage as an art form?

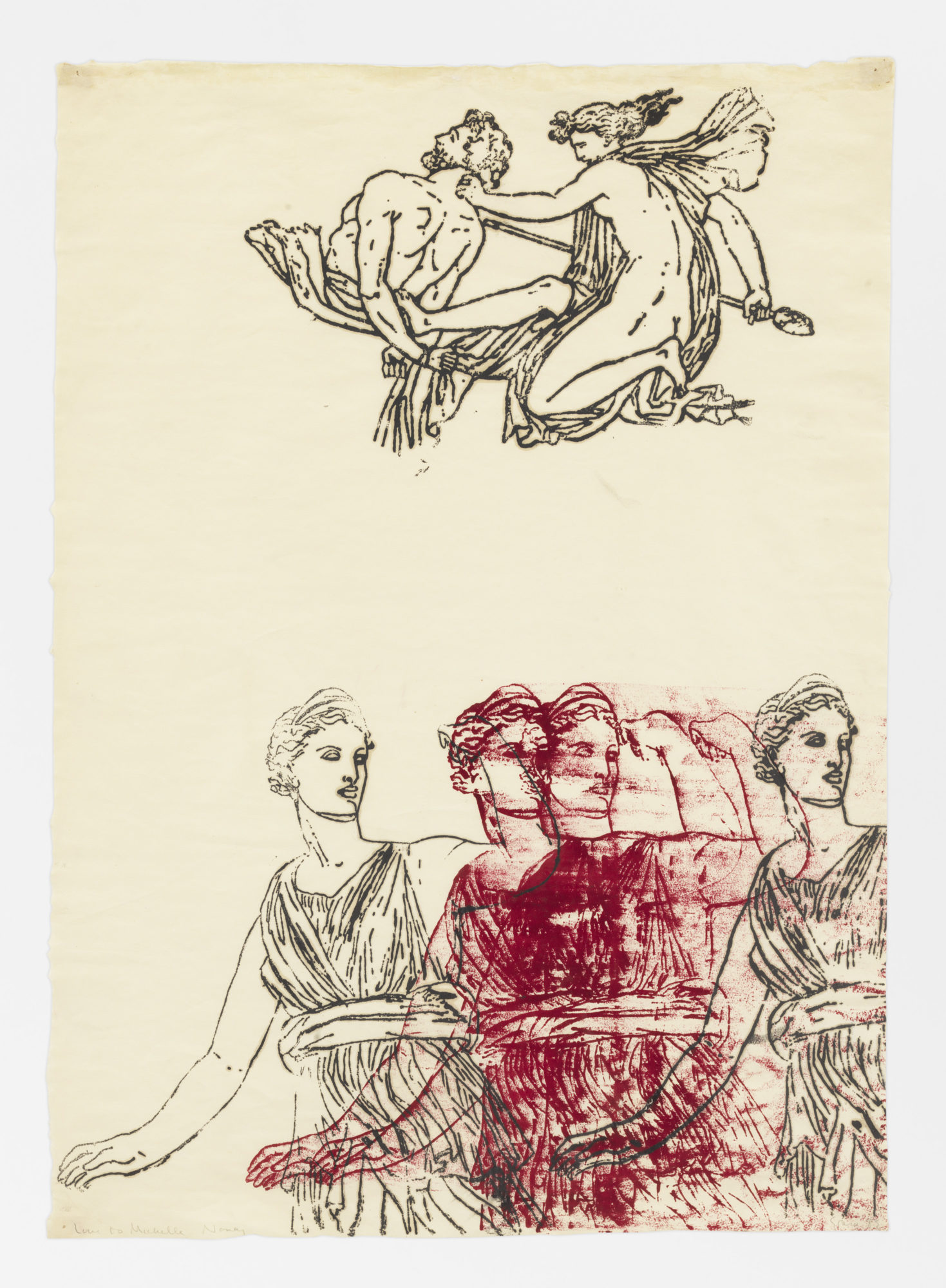

When I was researching for my thesis at Chelsea College of Art, I realised I loved the human form, not in a purely representational sense, but in a mythic, iconic, transformed and symbolic form. I saw this occur in the history of art, but I wanted to find this nearer to my lifetime in the era of modern art. It was then that I came across the collage books of Max Ernst – Une Semaine de Bonté and La Femme 100 Têtes. It was a revelation. I had not realised before that collage could be used in this seamless way to create whole new worlds of illusion! Max Ernst had used old engravings and pasted them together where you could not see the joins. Humans and creatures merged in this fantastic world of myth and dreams. I was fascinated and not only wrote my thesis on Max Ernst’s collage books, but created my own book of photographic collage, 50% The Visible Woman, as a homage.

Don't Look At Me in That Tone of Voice, photocollage from 50% The Visible Woman, 1969

Published in 1929, Max Ernst re-assembled nineteenth-century illustrations, constructing a loose narrative sequence of surrealist collages. La Femme 100 têtes is a double entendre; when read aloud it can be understood as either “the hundred-headed woman” or “the headless woman.”

Cover of 50% The Visible Woman, 1969

Surrealism was considered a man’s game. How did your expression of the feminine psyche advance the surrealist movement?

I wanted to turn the inside out of the woman before me, namely myself, and display the findings through the revolutionary tools of collage and its ability to remake reality. One can consider surrealism a movement in the history of art, or as an approach to reality – an artistic reinvention that is multi-faceted in its nature, untied to the rules of convention, and limited only by the extent of the imagination. I just took these tools and applied them to radical self-expression as a woman.

What does it mean to be your own muse?

It means you don’t ask anyone else to do anything you wouldn’t do yourself. And to make things even more straightforward, you do it yourself. You develop the ability to be in two places at once, the viewer and the viewed. You are presenting yourself through your own lens, subject and object all at once. On a very simple level, if we don’t find ourselves inspiring, that is a sorry state of affairs. There is endless inspiration in unravelling the mystery of the self and how it interacts with the world around it. It is fascinating to examine how we are seen and how we see ourselves.

“Making a spectacle of oneself. I have been doing that for a long time and am not stopping now, using my body at this age as my current muse. That is still a bit shocking.”

Rosebud, Original photograph and collage, Bride's Cake series, 1973

The Surprised Tin Opener, photocollage from 50% The Visible Woman, 1969

You shocked the art world with visual statements about how bodies are seen and objectified. Now that we live in an image culture where it is increasingly difficult to jolt an audience, what is the role of shock-value in the present moment?

The shock of recognition is probably the best jolt an artwork can offer. That recognition may come from a deep and hidden place, but in that moment of encounter, it can stir something deep within the viewer. I think intensity of purpose can feel shockingly real. Art done just for shock value may only have a brief life, but – when done with intrinsic conviction – will resonate beyond its times, even while being appropriate to them. Making a spectacle of oneself. I have been doing that for a long time and (am) not stopping now, using my body at this age as my current muse. That is still a bit shocking.

What are some misconceptions about the divine feminine?

I would prefer rather to define her qualities. What do we mean by the divine feminine? The goddess. She has many forms. The aspect of divinity which embraces all embodiment as well as all spirit, that brings awareness of the sacredness of all living things. As the rise of the feminine is upon us, to balance out the male domination that has been prevalent for so long, the wise know that for this new era to bring much needed transformation, it is the higher qualities – of compassion, cooperation, empathy and heart wisdom – that we all need to cultivate. These are attributes of the divine feminine and her imminence is best expressed by bringing these values into play as the guiding lights of the new feminisation of Earth.

Compromise to Form a Solution, photocollage from 50% The Visible Woman, 1969

Primal, photocollage on card from An Exorcism, 1969-77

In works such as An Exorcism and your recent collaboration with Dior, you play with the symbol of the house. What does that mean to you?

We all have to live somewhere, don't we? We live in our bodies, and those bodies for the most part live in clothes. Those clothed bodies live in houses. As with many other aspects of the mundane world, I like to take the elements of the house and shake them up and re-examine them. In my series of doll houses in the 70s, I transformed doll houses into harbingers of fantasies and dreams, abodes of the psyche and subconscious, not just material edifices. In An Exorcism, I took a large derelict mansion house and made it a container for the different aspects of my psyche, opening the door to each room to explore another aspect of my inner self. So I have used and continue to use the house as not just what it appears to be and its practical value, but as a symbol for, and exchangeable with, the body of a living being, haunted with the spirits that abide there.

“We do not want to become what we resist.”

What do you think needs radical rethinking in the art world?

It's not just the art world but the whole of culture and society that needs rethinking right now! Would we be on the brink of complete system failure of our whole ecosystem if we had been living by the right guiding principles? I think we are looking at a revolution occurring, where for the first time in history I know of, the art world is starting to take notice of women artists. I am particularly happy for this as I am a woman and I, along with other aspiring women artists, have been marginalised throughout art history as we know it – hoping this is our time to step into the light. If the energy of the feminine can really permeate the world of art, it will automatically create an internal revolution and shifting of values. Let's hope this comes to pass, both for the world of art and the world in general.

Is opting out of the art world a form of resistance?

The only career you affect by such resistance is your own! I did make choices that did not support my career as an artist. But life has woven me back into the art world, and for that I am very grateful, as – despite thinking that I could build my whole career outside of it – I found that I need to be in it to be visible. So I guess in life it’s a question of resisting or embracing where appropriate.

If You Can't Join Them.... photocollage on card from An Exorcism, 1969-77

“As the rise of the feminine is upon us, to balance out the male domination that has been prevalent for so long, the wise know that for this new era to bring much-needed transformation, it is the higher qualities – of compassion, cooperation, empathy and heart wisdom – that we all need to cultivate.”

What does liberation look like to you and how can resistance help us get there?

All that is born must die; that which outlasts these cycles is the only true liberation and that is the cultivation of the spirit which inhabits the flesh. While here on earth, I have been trying to free myself and by extension others from the things that bind them and stop them from reaching their true potential. High on that list has been the liberation of the feminine, as that energy had been stifled and suppressed for a very long time.

How that liberation looks to me is being free to express and embody the multidimensional beings that we truly are. Free to feel in our whole sentient bodies, with full sensitivity and awareness, capable of experiencing bliss.

As for resistance, we do not want to become what we resist, but it is useful to put practices in place that help us resist negative trains of thought. We can replace un-useful patterns of thought with positive ones. In whatever situation we find ourselves, the freedom of our consciousness is the only freedom we truly own and have control over.

The other resistance I can recommend is resisting following the patterns that are presented to us to live by. Just because there is common consensus in these matters does not mean it is the optimal choice. The holders of power seem to think they need to control people to ensure productivity, but this is mistaken. We are the most productive when we can do what we love. So resist the system in order to find out what you are passionate about, then embrace that with all you are.

Cover photo: Self Image, photocollage on card from An Exorcism, 1969-77. All images copyright Penny Slinger, courtesy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles and Richard Saltoun Gallery, London.

To delve deeper into the fascinating world of Penny Slinger, consider watching Out of the Shadows, a documentary by Richard Kovitch that details the untold story of Penny’s enigmatic career.