Human After All: Douglas Rushkoff

Algorithms, AI and surveillance capitalism are colonising the human mind, and it’s time for us to resist by rising to the occasion of our own humanity, claims renowned author and media theorist Douglas Rushkoff. William Alderwick plugs in to the matrix

“Well, honestly, and I can tell you this ’cos I can’t tell the London Times this, but Team Human is a media virus, a collective sigil, neurolinguistic reprogramming. The other books I wrote are information, they’re data and I create narrative around them. I’m telling stories about things. Team Human is almost a piece of literary software. It’s meant as an experience through which people can embed their brain with a programme that will help them resist the manipulative algorithms, platforms and systems that are out there. It’s a piece of cultural medicine.”

Douglas Rushkoff beams back conspiratorially from the other side of our video call. The author, broadcaster, former keyboardist for Genesis P-Orridge’s Psychic TV and oft-labelled heir to pioneering media theorist Marshall McLuhan is talking about his 20th book, Team Human. A manifesto split into 100 short sections, aka doses or ‘mimetic constructs’, the book – which shares its title with a weekly interview podcast Rushkoff has been hosting since 2016 – warns that anti-human agendas are being hard-baked into the technologies, markets and major cultural institutions that shape our lives. For Rushkoff, software engineers are framing us as the problem and technology as the solution. Not only are we in danger of writing ourselves out of the equation, he warns, but we’re faced with the prospect of the equations (AI as the first technology capable of writing its own algebra, if you will) originating and deploying their own tactics against us.

“Team Human is almost a piece of literary software. It’s meant as an experience through which people can embed their brain with a programme that will help them resist the manipulative algorithms, platforms and systems that are out there. It’s a piece of cultural medicine.”

Rushkoff says being human is a fundamentally, inescapably collective endeavour. It is a team sport. From the neurons up, what differentiates us as a species, and has enabled us to evolve biologically and socially to dominate the planet, is connection. He argues that we need to turn the narratives and values informing the digital architectures and infrastructures of our world away from those individuating, alienating and isolating us and towards rebuilding human connections and community. Team. Human. Two words, with a certain ring to them, at once pithy and powerful.

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Michel Foucault, 1975.

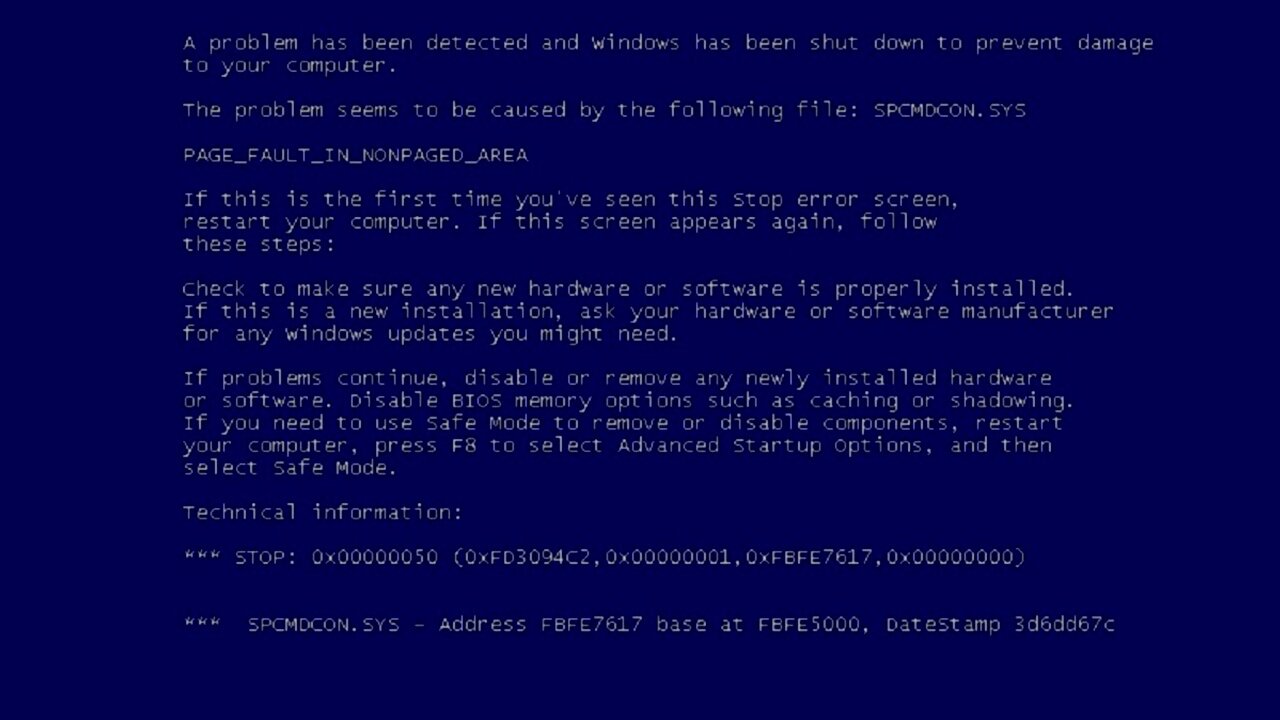

“It’s one thing to fight against these systems of social control in the era of Foucault,” says Rushkoff, referring to the French philosopher whose structural analysis of social power relations drew on the early prison system and Jeremy Bentham’s concept of the panopticon, where all the inmates within an institution could be observed by a single watcher without them being able to tell whether or not they were being watched. Unable to tell whether the all-seeing-eye at the heart of the prison is watching or not, the inmate has to act as if they are being observed at all times and thus internalises the regime’s prescribed behaviours. Social control becomes a function of visibility, and resistance a play of becoming invisible (or anonymous) and revealing the hidden (WikiLeaks, anyone?). “But it’s another when all these mean, controlling, panopticon techniques are embedded in a digital infrastructure that is teaching itself how to mine for exploits in the human psyche.

“This is going to be much, much more difficult to resist than previous forms of social control. They are, quite literally, colonising the human mind.”

—

From left: Richard Metzger, Paul Laffoley, Grant Morrison, and Douglas Rushkoff at the Disinfo Omega Retreat in 2004. Photo: William Alderwick.

I first met Rushkoff in upstate New York circa 2004 at a conference put on by the publisher and countercultural search engine Disinformation. Alongside the comic book writer Grant Morrison, the music PR guru turned sociobiologist Howard Bloom and the late visionary artist Paul Laffoley, Rushkoff presented his ideas about deconstructing digital and viral medias and heralded the possibilities of open-source “designer realities”.

Rushkoff had previously appeared on Disinformation’s late-night television show Disinfo Nation, put together by Richard Metzger (now behind the Dangerous Minds website) for Channel 4 in the UK. “If you don’t wonder if we made this stuff up, we’re not doing our jobs right,” Metzger would tell the viewer at the top of each show. It was a mix of visionary artists, conspiracy theorists, hactivists, magickians, countercultural remnants, activists, punk rockers, web pioneers and utopians, all served up with Metzger’s knowing smirk and impossibly raised eyebrow. In the middle of this carousel, the show’s intellectual lodestar was Rushkoff, the young media theorist. He made it a show that knew it was a show. Disinfo Nation not only played with the format and expectations of viewers, but with Rushkoff, it told you what it was doing and how at the same time.

Back at the conference, somewhere between Laffoley discussing blueprints for a working time machine and Morrison explaining how he uses sigil magick to hack reality, Rushkoff reiterated his media virus concept: advertising, and all media really, works just like a virus attacking a cell in the body. The outside is covered with all these pretty, shiny and attractive things to hook us in. Once we’re latched on and consuming the media, then the message at its core, the viral DNA, is injected straight into the nuclei of our brains – bypassing the critical thinking of the neocortex and targeting our reptilian autonomics. It’s as simple as “enjoy Coca-Cola”. Advertising forges neurolinguistic links between, in this case, enjoyment and any desire for it with the product or brand. Once that link is made, just like pioneering psychiatrist Milton Erickson’s use of hypnosis in therapy, everything that follows is about reinforcing that prime suggestion, until it is unwaveringly assumed as a given. It’s as simple as “team human”.

“All media works just like a virus attacking a cell in the body. ... It’s as simple as “enjoy Coca-Cola”. Advertising forges neurolinguistic links between, in this case, enjoyment and any desire for it with the product or brand.”

When did he first became aware of the dangers of an anti-human agenda creeping into our software and technologies? “Honestly, it was around 1993,” he says. “I had written Cyberia, my first book, on rave, internet, fantasy role-playing and all these weird psychedelic subcultures, in 91 and 92. It got cancelled because the publisher thought the internet would be over by 93. Then it got bought by HarperCollins, and I had time then to rewrite the end of the book. Since I finished the first draft Wired magazine had launched. Wired was the first magazine other than Mondo 2000 to be saying: ‘Something is coming that’s bigger than just PC Magazine’s story about new RAM.’

“Only this very psychedelic thing I had been writing about, what Timothy Leary was calling the technological LSD, was being framed in an alternative setting by the Californian libertarians of Wired. Instead of it being this story of the collective imagination creating a designer reality and us hallucinating ourselves into the Gaia hypothesis, which was my story and the story of all my little peyote-eating friends, it became this other story of: ‘Oh, here is the new method for extending extractive growth-based corporate capitalism into the next century.

Cover of Douglas Rushkoff’s Cyberia: Life in the Trenches of Hyperspace.

“At the end of Cyberia I wrote that whoever frames this reality is going to get to own it. I still believed (then) that these guys were going to lose because they’re sold-out yuppie scum and we all know that they’re assholes. ‘We’ve already seen Bart Simpson and Rodney King, and we’re awake, we’re woke!’ You know? 1994 America, right?

“Coercion was really the bigger turning point.” Like the special sunglasses in John Carpenter’s seminal classic They Live, Rushkoff’s 1999 book Coercion: Why We Listen to What “They” Say laid bare the tricks and manipulations used by marketers, con artists and salespeople of all levels. For example, how door-to-door salesmen would shadow the breathing patterns and cadence of their marks, mimicking postures and gestures to foster artificial feelings of connection and empathy, thus making the targets receptive to bring led to the dotted line. Rushkoff explained how these kinds of techniques were starting to be adapted into the nascent digital ecologies and used to behaviourally engineer situations online.

Cover of Douglas Rushkoff’s Coercion, 1999.

“Coercion was saying: ‘There’s an arms race between us and the controllers. They are upscaling their tactics, using digital technology, they’re embedding the digital infrastructure with regression and transference and neurolinguistic programming.’ That was in ’99, before (behaviour scientist) BJ Fogg started his ‘captology' department at Stanford.

“And then the rest of the books have really been about that power relationship: it’s program or be programmed. If we don’t understand the landscape and they do, then they’re going to control us. If you’re not the real user, then you’re the used.

“Team Human is meant to be an optimistic call to arms rather than a critique of technology. I thought it could augment the human organism, strengthen our cultural vitality, rather than just deconstruct and reify the centrality of digital control mechanisms.”

“To have any IRL connection or community now necessitates having a car. Is that freedom, or a straitjacket? ”

In his writings Rushkoff often uses a technique a bit like those Rubin’s vase optical illusions where shifting the focus of your eyes can reveal either a vase or two faces looking at each other. By flipping a narrative on its head, inverting figure and (back)ground, he reveals things we’ve overlooked in a situation – how, for example, money, automobiles or universal education have changed us and our lives in unanticipated and counterintuitive ways, often not for the better and against their original intentions. Automobiles, he observes, were first marketed to the working classes through the aspirational freedom of enjoying the open roads on their newly won two days off at the weekend – the Fordist utopia. A couple of generations later, with gridlock in urban centres and exhaust emissions choking the air, the automobile has transformed American towns by enabling the exodus from civic centres and main streets into soulless suburbs. To have any IRL connection or community now necessitates having a car. Is that freedom, or a straitjacket?

Another of Rushkoff’s favourites is universal education: launched as compensation for industrial work and presented as a celebration of human dignity through self-betterment and knowledge for its own sake. Instead, he suggests, education has become an extension of work itself, externalising corporations’ costs of training staff. Our schooling is now about our utilitarian value as potential employees (our salary potential, read credit rating), not dignity or quality of life.

“My experience comes from theatre,” he offers when asked about these shifts of perspective. “Almost every Shakespeare play has a meta-theatrical moment, a play within the play. Or someone observing a scene from the outside, spying and they make some comment like: ‘I wonder if someone is watching us as we watch them.’ As if referring to the audience. It’s those meta-moments that help figure become ground (i.e. the Rubin’s vase effect). It’s what The Simpsons does, it’s what Mystery Science Theater does, it’s what Beavis and Butthead did.

“The videos that Beavis and Butthead watch end up having the opposite effect of what’s intended. When Beavis and Butthead comment on two breasts in a rock video, all of a sudden the breasts are now no longer the object of hypnosis but they’re what calls attention to the hypnotic spell of the filmmaker or advertiser. It reverses the intention – it’s like a very advanced form of heckling, but it brings things into consciousness.

“I was always interested in those kinds of reframings. McLuhan talked about the same thing, how in a new media age the prior medium becomes the content of the next one. Now television is the content of the internet.

Credit: Devin Doyle.

“When I was growing up, I was interested in theatre and medicine. Shaw was a doctor, Chekhov was a doctor. Surgeons work in ‘operating theatres’. To me, the commonality between them is looking at what animates life. Are we some biological survival need that creates consciousness and awareness in order to perpetuate it? Or is it awareness that creates biological entities in order to have something to inhabit? And we just really don’t quite know.”

Rushkoff’s words remind me of an interview I did with Paul Laffoley, who was complaining about string theorists adding more and more dimensions into their theories (we’re at 10 or 11 now). And Laffoley was like: “They’re adding these new dimensions like filing drawers but they’re not thinking about what it’s like to be alive in there.” I tell Rushkoff how that always spiked me. What is the thing that lives and breathes within this space? What’s the experience like inside the drawer?

“McLuhan talked about the same thing, how in a new media age the prior medium becomes the content of the next one. Now television is the content of the internet.”

“And that’s my problem with most movies, TV and novels now,” Rushkoff says. “They’re adding layers of complexity – now we’ll tell the story backwards in time, or on three different time loops – but it’s just postmodern pyrotechnics more than a real exploration of what’s the actual lived experience.”

Which is the essence of storytelling, I suppose. “You would think, yeah. There’s something much simpler that we’re not reckoning with and that’s why Team Human, in some ways, is pathetically naïve or simplistic.”

––

Earlier in the year, in the upstairs bar of a pub round the back of King’s Cross railway station in London, I had pressed a folded-up copy of the second issue of Good Trouble into Rushkoff’s hands. As he opened out the broadsheet, his eyes were wide and smiling through the hubbub of drinking, chatter and music that filled the room. A talk earlier that evening at the British Library, moderated by the Guardian columnist George Monbiot, was my first encounter with the ideas of Team Human, even though Rushkoff had been doing his podcast for several years. The podcast started when he took a short break from writing after landing the role of professor of media theory and digital economics at Queens College, City University of New York, in 2014; it served as a “listening tour” through which he could see what other people were talking about and use his platform to give them voice. The ideas for the book, informed by the podcast interviews, evolved out of Rushkoff’s monologues on the show, “a distillation of that year of public thinking”.

As we chatted in that bar, half-shouting through the din in the bar’s half-light, a wariness brought on by the nationalistic anti-immigrant rhetorics of Brexit made me ask: who gets to define who gets on the team, who gets to define the ‘human’? Within the book, there’s not really a definition of what being human means per se. Rushkoff talks of it in a very natural, almost naïve way. The closest he gets to a defining quality is that through our language we’re able to bind time, literally replaying and reliving past events through storytelling, and thus pass knowledge between generations. There’s a radical openness suggested by this lack of definition, that being human is whatever you want it to be, and that that’s the point.

“This is going to be much, much more difficult to resist than previous forms of social control. They are, quite literally, colonising the human mind.”

“I think the jury’s still out on what humans are, you know?” he says. “And I think that that’s okay. The only ones who really want me to define what being human is are the artificial intelligence people. And if I can’t give them a metric for what humanity is, then humanity doesn’t deserve a place in their future.

“It’s almost like the part that we can’t articulate is the part that’s the most important. The closest I can say to it is: the formal cause of human beings is the soul. And that’s the part that’s just so confounding to capitalism and to science. But soul is not some supernatural thing, you know? You could argue it’s the same thing that Al Green or Otis Redding have. What is that? It’s the thing that goes away when you auto-tune their voices.”

“Humanity is the noise,” Rushkoff says. “It might not even be the signal – we’re the noise.”

In the book, Rushkoff points out that resistance is a metaphor from a bygone age, whether of the political, activist or Star Wars variety. In a digital media environment, there is no resistance as attenuation. Binary logic reduces everything to either one or other, on or off. There is no resistance, only opposition. Musical compression algorithms aren’t designed to represent music accurately, but to fool us into believing that we are hearing it accurately. The rich sonorous ripples of acoustic waveforms are clipped. Performers’ voices are auto-tuned and quantised to a metronomic ‘perfect’ beat. All human quirks and character, everything that’s on a spectrum, comes across as an imperfection in a digital world that reduces everything to a datascape of ones or zeros. The grey areas in between disappear.

“Humanity is the noise,” Rushkoff says. “It might not even be the signal – we’re the noise.” And if we’re optimising ourselves for the technology and not the other way around, are all human traits not favoured by the market (racial diversity, gender fluidity, sexual orientations or proclivities, body types or religious predilections) potentially in danger of being deselected, abandoned or overwritten?

By Devin Doyle

“That’s the thing,” Rushkoff says. “The disease is this stark intentionality and this ability to optimise everything really for control and safety and lack of challenge. And humanity is something else! It’s this messy, boundary condition. It’s one expression of nature, one way of manifesting evolution’s social urge.

“Even with something like Extinction Rebellion, there’s a certain element of play. They want it to be fun, a way of eliciting love and sex and these vital human energies. I do think we’re more human when we’re at play, and that part of rapport is a playfulness.”

What emerges through Team Human is not a revolutionary message of overturning the tables and violently taking to the streets. What Rushkoff suggests in terms of action is almost prosaic: being visible, engaging in protests, participating politically and developing new platforms, engaging purposely with the natural world, reforming corrupt institutions and building better ones. The core message seems to be that we just need to participate more.

“It’s not an activist blueprint,” Rushkoff admits. “It’s a call for something more fundamental than that. I would think activism, direct activism, social change and social justice work would be an obvious next step. But I’m asking that people retrieve these essential human values, and that then necessitates a whole lot of action. In some sense, it’s a pre-activist message. But, if you don’t value humanity, if you don’t value yourself and these connections with others, then I don’t know if that will ever get there.”

As he points out, technology itself doesn’t inherently want anything. Whatever drive or purpose it has comes entirely from the software that we program it with, from the underlying logical value systems that we design and utilise it within. The real target of Team Human is this underlying value system: capitalism. Extractive and exploitative capitalism. The book is an attempt to shift our perspective, invert figure and ground, to help us shift our values away from capitalist value extraction, from a winner-takes-all to an all-take-the-winnings kind of logic.

“I’m arguing for pre-distributing the means of production,” Rushkoff says. “What does it mean for the workers to own and for us to own the world? A few corporations beginning in the days of the British East India Trading Company have been gobbling up more and more of our reality. And this process has been naturalised. Now that we’re facing water crises, they’re buying up the water. Human beings have become just another medium for corporate extraction. Our whole race, our whole planet, our whole everything has been surrendered to a very short-sighted economic model that was developed to slow the rise of the middle class in the 11th century. If we are going to keep that model, if we want to believe in that model more than ourselves, then we’re about to pay the price.

“I try to make a distinction between revolution and renaissance. A revolution is a turn of the cycle. A renaissance is the retrieval of old ideas in a new context. I trace a lot of our current problems back to the last renaissance. For all the cool things about it, it was also the retrieval of very specific ideas from ancient Rome and Greece about centrality and control and the repression and obsolescence of women, magic, indigenous people, spirit and peer-to-peer economics. All the things that were forcibly suppressed during that time really need to be retrieved now, or we all die.

“But in terms of the reception of the ideas, I feel like the time is right. People really do want to join Team Human. They want to entertain the possibility of humanity making it another century or two. They have just enough hope that thinking that our children might live out their natural lives is a daring belief to entertain.”

By Devin Doyle

The final dose of Team Human’s cultural medicine is to ‘Find the others’. “I’m lucky because I was old enough to meet most of my ‘others’: Timothy Leary and Robert Anton Wilson and Terence McKenna, [Mondo 2000’s] RU Sirius. They were my first others and there were others at college. But honestly, for a long time the tell-tale marker for finding a fellow traveller was, did they have psychedelic experience? And I’m not saying that psychedelic experience is required to understand the world, or anything like that, it’s just that in 1980s, Republican, Reagan America, if you were one of the 12 people at Princeton who took acid in 1980, it meant a whole lot of other things about you at the time. It meant you listened to Brian Eno. That you were already exploring the figure-ground relationships between humans and society. It meant that you had read William Burroughs and thought about the deconstruction of media and cut-and-paste. These people had been turned on to the system’s iterative reality and the whole notion that we are participating actively in the creation of reality. “But then, more recently, as I started writing Team Human, the notion of ‘the others’ expanded from the others who have had the great psychedelic experience to the true others, the kids with the Make America Great Again hats… These are human beings, and I keep arguing that we’ve got to see them as humans if we want them to see Mexican immigrants as humans.”

“I try to make a distinction between revolution and renaissance. A revolution is a turn of the cycle. A renaissance is the retrieval of old ideas in a new context.”

The destruction wrought by European colonialists led Native Americans to conclude that the invaders must have a disease: wettiko, a delusional belief born from people’s inability to see themselves as enmeshed and interdependent parts of their natural environment. This disconnect leads them to see nature as something to be conquered and consumed rather than emulated and sustained. Team Human argues that the only way to escape this sickness is to shift perspective, widen context, re-situate the terms of debate, invert figure and ground, reverse the polarity. The whole book is an attempt to refocus our attention on what matters to us, on what makes us human, and on what we truly care about. We are not the problem; we’re the solution. Rushkoff calls for us to reconnect with the ground on which we stand, the communities we live in and the people with whom we conspire – literally those we ‘breathe together’ with.

After our interview, an email pops up in my inbox from Rushkoff, perhaps embodying the uncomplicated, open-handed outreach at the heart of his Team Human message. It reads simply: “Let’s stay friends.”

Go find the others.

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.