Taking History: Steve Schapiro

When history was being made, he was there with camera in hand. At the outset of his remarkable six-decade career as a photographer, Steve Schapiro was responsible for some of the most iconic images of the American Civil Rights movement. Aged 85, he sat down with Florian Sturm (in 2019) to reflect on the death of Martin Luther King, traveling with James Baldwin, and why he’s still learning his craft

Words by Florian Sturm / Images by Steve Schapiro / Taken from the third issue of Good Trouble magazine, available now

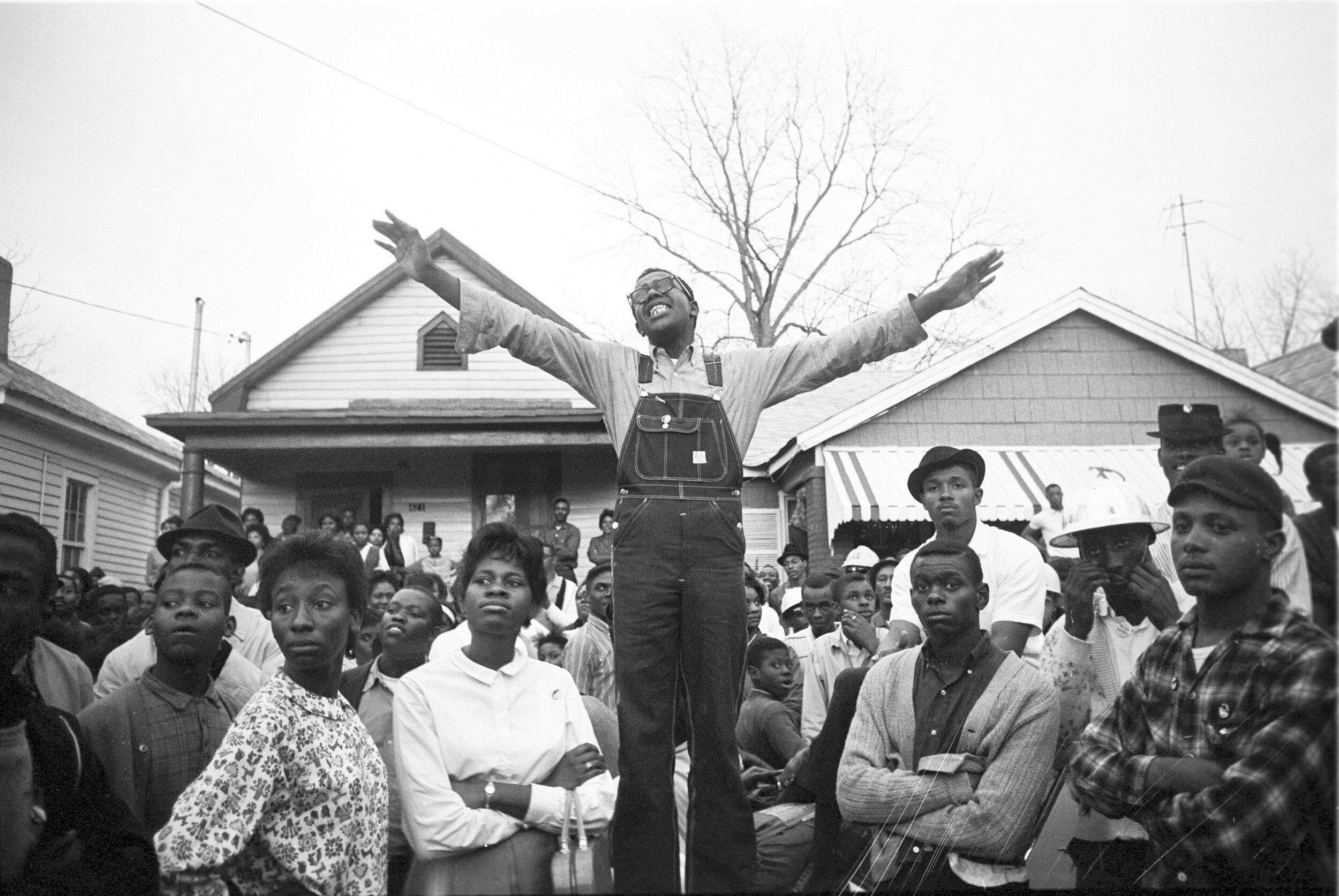

There is probably no other photojournalist who covered the American civil rights movement in such an ‘embedded’ way as Steve Schapiro. The Brooklyn-born photographer documented history on the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963, and the Selma to Montgomery marches two years later. Since the beginning of his freelance career in 1961, Schapiro has followed a lifelong interest in social documentary and a humanistic approach to photography. That’s why he was never really able to separate his roles of photographer and activist, whether photographing stories about migrant workers in Arkansas and drug addicts in Harlem, following James Baldwin on his speaking tour through the US, and accompanying Robert Kennedy during his 1968 presidential campaign.

Schapiro’s images have been published in magazines such as Life, Look, Time, Newsweek, People, Paris Match, Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair. In the 70s, he began working for film studios and produced iconic stills for movies such as The Godfather and Taxi Driver, before celebrity portraiture became another of his additional professional footholds (Muhammad Ali, Andy Warhol, Ray Charles, Samuel Beckett, Robert de Niro, David Bowie and Jodie Foster, to name a few). Schapiro remains active in photography to this day, having recently documented the Black Lives Matter movement and produced reportage from India.

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, MARTIN LUTHER KING JR’s ROOM OF THE LORRAINE MOTEL. 1969

Which image comes to mind when you think of your career that lasts almost six decades?

There are various, actually, because you've got all those different phases of my work. One of my favourite photos is a Martin Luther King picture. When he was shot, I went to the room of the Lorraine Motel, where he had stayed. On a ledge was an open attaché case with all different things in it. Right next to it were a few shirts, as well as used Styrofoam cups. One the wall sat a television set and the image of King came up behind the commentator. I photographed this whole scene as one picture. To me it's quite a strong photograph as the physical man was gone forever, yet his material things remained and he still hovers above us in a way.

You've been associated with many key moments of US history and culture. Did you realise the importance of your photos during the events itself?

No. A lot of these pictures were shot in the 1960s and 70s, the golden age of photojournalism. At that time, there were no galleries or anything of this sort. Back then, you didn't think while you were taking pictures that they would be seen 50 years later. Instead, as a photographer, you shot during the day, sent off your film and may not see any of your contact sheets for weeks because you were doing something else. Your basic concern was: do I have a picture that will appear in the magazine next week? That's what you aspired to at the time. Even if you did think you were covering an important moment, it was important at the time, specifically on that day or the next few days. You would not, however, think of it in terms of historical perspective in a sense in which we do now.

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. WITH FLAG DURING THE SELMA MARCH, SELMA, ALABAMA, 1965

“Back then, you didn’t think while you were taking pictures that they would be seen 50 years later… Your basic concern was: do I have a picture that will appear in the magazine next week?”

How did you first get into photographing the civil rights movement?

Through James Baldwin. In 1962, he published 'The Fire Next Time' about the black situation in America. I read the piece and was moved by it. Back then, I had just started freelancing on a bigger scale for Life. I asked the editors if I could do an essay on him. They agreed, he agreed. And that's how we started travelling. He had a speaking tour which took us to North Carolina, Mississippi, New Orleans. Through that, I did not only meet a lot of people but also saw a world which was something I had heard about but never experienced thus far – a world very different to the one I saw in New York.

When you accompanied Baldwin on his tour, was there ever a moment when your inner mindset switched from 'I want to document what he does' to ‘I want to support his political agenda’?

He exposed me to an emotional conflict which was happening at this time and which was elemental to the civil rights movement. Nevertheless, I always tried to photograph as objectively as possible, even if I did not support the opinion of these people. For example, I also spent quite some time photographing segregationists in St Augustine, Florida.

Letterpress edition of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time with photographs by Steve Schapiro

Did photography back then have the potential to actually bring about change?

Some of them certainly did. Charles Moore covered the civil rights movement in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. (Moore’s pictures) were very important photos in terms of proving that photojournalism is actually effective. Those pictures changed the attitude of America regarding what was happening to the black community in the south.

How can photographs help people or society in general go through rough political times today?

Currently, things are so overwhelmed regarding the president we have that images have lost some of their power. Sometimes an image helps you to understand a person or something about them. This man exemplifies who he is every time he opens his mouth. We're in the middle of a very bad and dangerous situation.

Another reason for the decreasing influence of images is simply the unlimited availability. Photography is everywhere these days.

That's true as well. We see so many pictures that our mind hardly ever singles out one specific image to represent a whole viewpoint.

Can there be iconic images then?

Creating truly iconic images today comes down to the question of seeing things differently. I mean, how does the evolution of art work? You've got the impressionists who were mocked by their times, you have the pop movement in America, which at first was belittled and now is extremely important. That way, you always have new ideas coming up and art is always at the forefront of many things. Sometimes they are hardly noticed, sometimes they shock – but that way, they open up new ways of thinking for many people. Art has the potential to really change the morality of a nation or even the world. Photography does, too, but the innovative potential isn't as big.

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, MUHAMMAD ALI (CASSIUS CLAY) WITH MUSCLES, LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY, 1963

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, BARBRA STREISAND IN THE BATHTUB, LOS ANGELES, 1974

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, ANDY WARHOL MIMES MARGARET KEANE “WAIF”, NEW YORK, 1965

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, RAY CHARLES HUGGING, NEW JERSEY, 1966

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, DAVID BOWIE WITH MOTORCYCLE, LOS ANGELES, 1974

In what way does this photographic overload we are exposed to today also come into play in terms of the innovative potential of photography?

There were a lot less photographers. About five or six really good ones documenting the civil rights movement. This has all changed now. Four months ago, I saw a picture of Obama in the New York Times. It was a sensational image. And yet it's gone because there are so many pictures these days. Whereas you used to depend on big magazines to see images of what was happening in the world, everybody has a smartphone now.

Does this photography overload and citizen photojournalism impact you in any way as a professional photographer?

No, because it still is important who you are. We all have a different points of view and a different way of looking at things. On the Selma march, they were three really good photographers – Bruce Davidson, James Karales and me. We all covered the same event and even shot the same boy who had ‘Vote’ written in big letters on his forehead. But all photos are different.

© STEVE SCHAPIRO, THE WORST IS YET TO COME, NEW YORK, 1965

How has witnessing these numerous pivotal moments in history changed your personal perspective on life?

It hasn’t. (Turns around and asks his wife, Maura) Has it changed my view on life, Maura?

Maura: Of course it has! Most of what Steve does now is taking pictures of protests and social issues. Whenever I say to him, you know, so-and-so is coming to Chicago and you should see if they want to do a photo, he always goes: ‘No.’

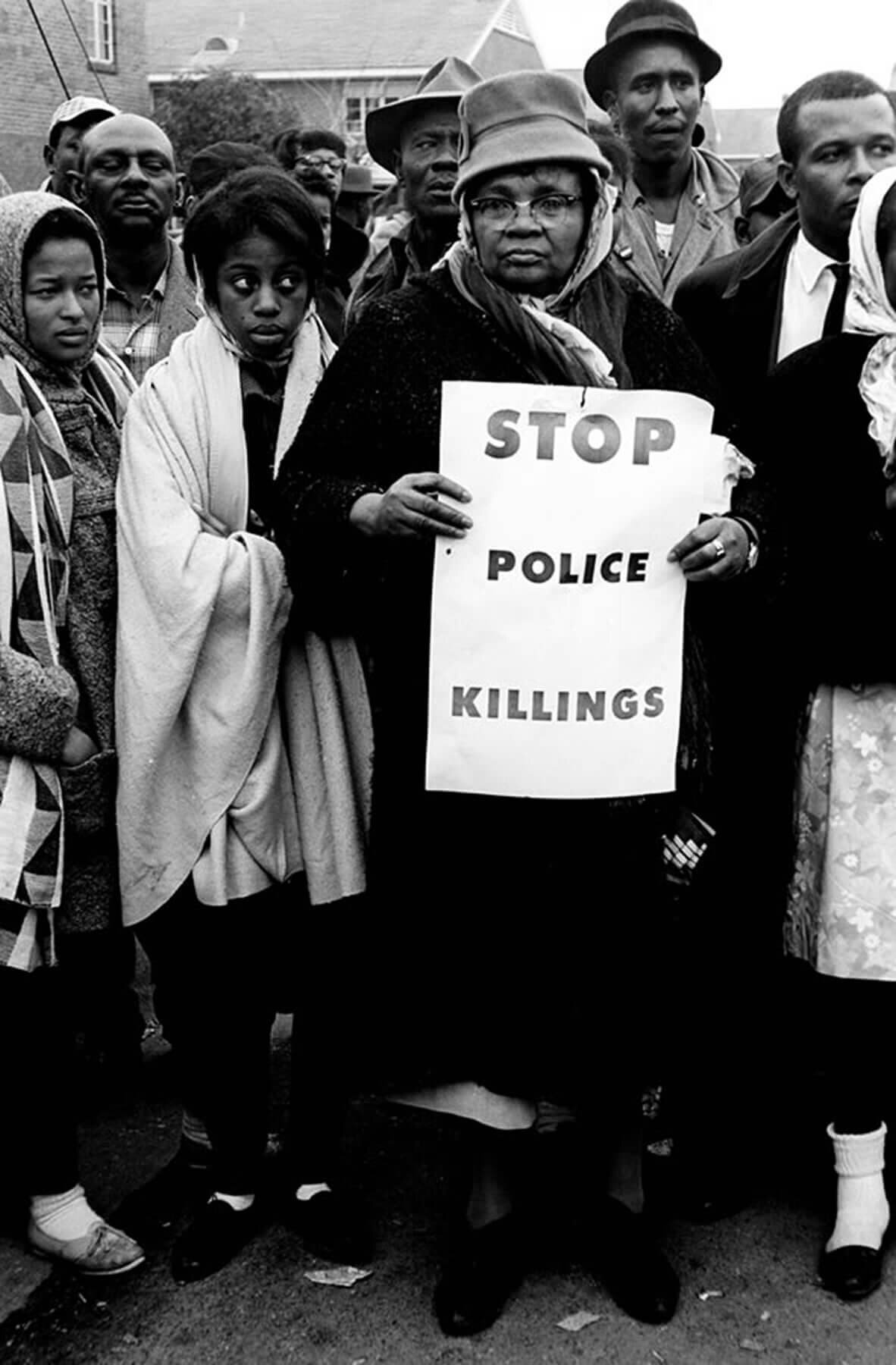

Stop Police Killing © Steve Schapiro

You photographed the civil rights movement, police aggression, segregation and racism five decades ago. Now that we're experiencing a similar political atmosphere in the United States, do you ever think: ‘We've been through that, haven't we’?

There's a picture I did in 1965 of a middle-aged black woman. She's holding up a sign which reads 'Stop Police Killings’. For me, that resonates today the same way. There may not be as many situations and not all troopers are there to stop a nonviolent movement, but individual members of the police still appear in a very aggressive nature.

Maura: Steve, do you think a photographer can counteract this current situation with Trump with different images and show another side of America?

I think so, but right now America is extremely engrossed in set emotionalism on both sides that it's not going to change much. Charles Moore's pictures of Alabama, however, changed America, because the country was undecided. People simply did not understand what was happening in the south. Today, you have people who understand what's going on and they either support Trump and say, ‘Don't mind what he talks, because what he does is great for America,’ or who oppose him and think that he is a danger to democracy in general.

“Many people say a picture never lies. But it does.”

You once said: “In the world of photography, nothing is real. Above all, you cannot equate it with the truth… The truth lies in the hands of the photographer editor. They decide what is true.” What do you mean by that?

The photographer decides when to push the button and we assume that’s truth. On the one hand, it is, but on the other hand, it only gives us a fraction of time, a fraction of truth. Ultimately, it's the editor who decides which image to use, and by that shapes the narrative for a whole nation or even the world.

Can you give an example?

Take Alfred Eisenstaedt's famous image that he took of Joseph Goebbels in 1933 – Goebbels was sitting in his stiff chair, with this demonic look on his face and an aide hovering over him, all in black suits. 15 minutes prior to that, Eisenstaedt photographed Goebbels with a huge smile. Both these pictures went to Time magazine and it was the editor's choice of which image was going to give people an idea of where the Nazi regime was at or where it could lead. Many people say a picture never lies. But it does.

Do you think a photojournalist needs to have a certain talent to capture the uniqueness in an event or a person?

It's who you are and how you react to things. I always liked to follow someone who has come before you and try to copy him.

In your case, Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Right. He has been one of the all-time greats to watch. There certainly were times when I was trying to copy his particular style.

What fascinates you about him?

The fact he was able to catch things at the height of their moment, that he had a great sense of design in his photographs, and at the same time gave you some information about the situation he was capturing. But most of all, he hit an emotional, sometimes extremely symbolic moment regarding his subject – even if he was just capturing Henri Matisse in his studio. There was something about the photograph that made you want to come back to it.

Was there a key moment when you yourself were certain you could earn enough money photographing?

I never thought about that very much. It really wasn't a concern of mine. I just became interested in trying to take better images. Initially, I felt I was a second-grade photographer. Hence, I was constantly asking myself how to get better. I'm still trying to figure that out today. I don't feel I've mastered the craft to perfection. Far from that. But I still have time.

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.