Ice and Emergency: Olafur Eliasson

Experience the urgency of Olafur Eliasson – superstar artist, environmental activist, radical designer. Here, He talks to Francesca Gavin about bringing to life the horror of melting glaciers, and putting the power of the sun in people’s hands

Olafur Eliasson has reinvented what it means to be an artist, and his studio has transformed art into a platform to examine our relationship with the natural world. The climate crisis is at the crux of everything he does – from wildly popular installations such as The Weather Project at the Tate Modern in 2003 to kaleidoscopic sculptures, photographs and watercolours, even a portable electric light shaped like a flower.

Eliasson, who has been based in Berlin since 1995, has a studio that functions as more than a space for art production – it is an experimental think-tank researching and producing active, often beautiful objects and engagements that bring everything back to our environment. Eliasson is from Denmark with Icelandic roots, and he has talked about how going back to Iceland has been one of the most motivating forces in his work.

“As Eliasson noted at the time: ‘Every glacier lost reflects our inaction’.”

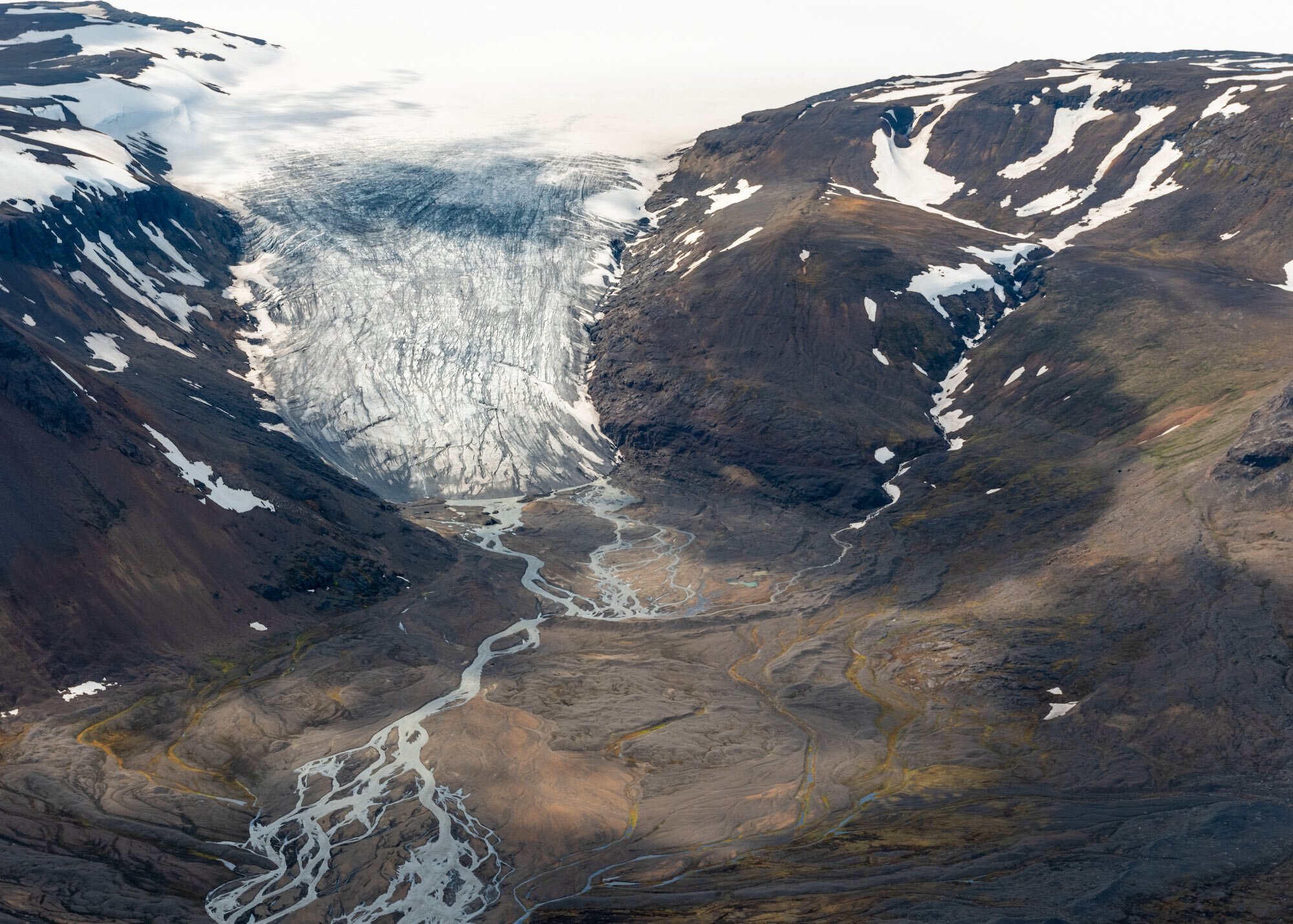

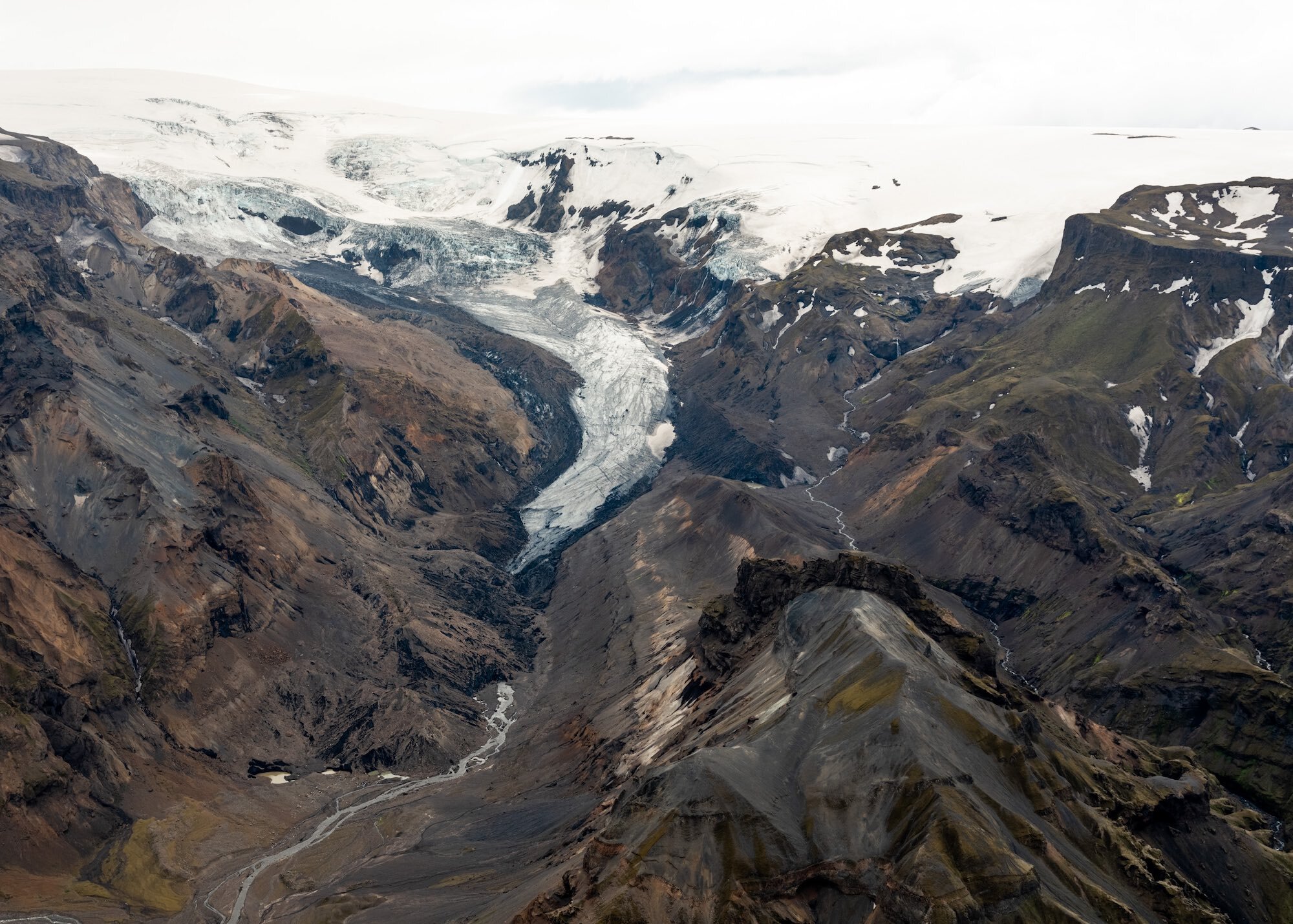

“A letter to the future – Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it. August 2019. 415 ppm CO2” – writer and poet Andri Snær Magnason, on a plaque installed at the site of the melted glacier Ok (Okjökull) in Iceland. Photograph by Olafur Eliasson (2019), published on the cover of Good Trouble Issue 21

In the lead-up to 2019’s major exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, he created Ice Watch, transporting large lumps of glacial ice outside of the museum so visitors could feel them, touch them, and watch their steady and final disappearance. It evoked the terrifying death of the Icelandic glacier Okjökull (right), which has now vanished due to climate change; the country’s government recently installed a plaque at the top of where it once stood. As Eliasson noted at the time: “Every glacier lost reflects our inaction.”

In his world, art is the inspiration for solution and discussion, not part of the problem. He is now collaborating with companies such as Ikea and the Little Sun Foundation to create things that have an active influence on how the world can function and move away from the tech-fix throwaway society we now inhabit. Ultimately, what makes his work so powerful, and what has garnered him serious recognition with presentations at the Venice Biennale and museums around the world, is his balance of science and activism with beauty.

The glacial landscape of Iceland has been a huge influence on your work. How have you been affected by the changes you have witnessed and documented in this landscape?

I spent a lot of time in Iceland as a child with my father and grandparents. It always fascinated me as an environment that was so extremely different from where I grew up in Denmark. For me, Iceland really represented nature, and Denmark was culture. Of course, I have since come to realise this was a very naïve view, considering the extent to which the Icelandic landscape has been shaped by human activity over the years, and especially since the settlers effectively deforested the island hundreds of years ago. But it occurred to me that the Icelandic landscape is underrepresented in art history. I began taking photographs there in the early 90s, and have created more than 80 series of photographs.

I exhibit these as typological grids, with each focused on a particular aspect of the Icelandic landscape – volcanoes, hiking shelters, caves, waterfalls, glaciers. I am currently working on photographing the same sites that were featured in The Glacier Series (1999), which documented a selection of glaciers taken from the air. It’s shocking to see how much the glaciers have melted in the last 20 years.

“It’s shocking to see how much the glaciers have melted in the last 20 years”

The Glacier Series (1999/2019), gallery view

Do you think art has a role to create change in relation to our environmental future, and how do might that function?

I think one of the most effective things art can do, in addition to raising awareness, is to offer a concrete experience of the reality of climate change. Art can help people feel the reality of something that seems so large and far away. It can make it tangible.

Ice Watch by Olafur Eliasson, photographed by Justin Sutcliffe

Ice Watch is a perfect example of how this can work. Visitors who encountered the 120 tonnes of Greenlandic glacial ice in London were able to reach out and touch the effects of climate change. The bubbles popping as it melted released air from a time period in which the atmosphere had far less carbon in it. This experience of this massive timescale, I hope, will motivate people to become involved and act together to pressure our governments and businesses to make changes on a systemic level, which is the only way we will succeed in responding to this crisis.

“I think one of the most effective things art can do, in addition to raising awareness, is to offer a concrete experience of the reality of climate change”

Your Spiral View (2002), Olafur Eliasson In Real Life at Tate Modern, 2019. Photograph by Anders Sune Berg

The last room in your recent Tate Modern show was devoted to research and development. It seemed to be creating a platform for discussion, action and the dissemination of knowledge. Can you tell us more about this side of your practice?

I approach research first of all from the perspective of an artist, rather than a scholar or scientist. Research at my studio can make its way into a project from various angles. There are of course some very practical research topics related to making individual works of art, having to do with geometry or materials, for example. But there are also areas of research that are less easily applied to the creation of objects, and have more to do with my ongoing discussions with outside partners, thinkers, scientists and theorists who come to visit my studio.

soe.tv is dedicated to the video output of the studio

For a number of years, I have translated much of this thinking into publications or events like Life Is Space – a series of day-long meetings to which I invited people who were working on a broad range of topics that interested me, and brought them together with others involved in different, perhaps unrelated, activities. More recently, my team and I have been recording some of these conversations on my soe.tv website, dedicated to the video output of the studio. Social media has also given me new ways of thinking about the discourse around an artwork. Ultimately, however, the research is all driven by what inspires the work – even where this may not be immediately visible.

It is interesting that you have been measuring the carbon footprint of the creation of your own work. Having learned this information, how has it affected how you make exhibitions, new work and installations?

Assessing the carbon footprint of a work is the first step towards gaining a new ecological awareness at the studio, and we are now in the process of developing and instituting a sustainability plan. It’s an incredibly complex topic once you delve into it, and there is a lot of ignorance and confusion out there. Everything we do affects everything else in the world. Anyone who has tried to live more ecologically has encountered this problem – is it worse to buy a milk carton or use a glass-deposit system? Maybe the glass system actually consumes more energy because of transport costs, whereas the carton is only partially recycled.

“There are no simple solutions. But we cannot not act, simply because the solutions are difficult.”

There are no simple solutions. But we cannot not act, simply because the solutions are difficult. The carbon footprint is an invitation to others to engage in this discussion. Eventually, I would like to make what we have learned public, for other artists’ studios to adopt and adapt for themselves.

Can you tell us about the latest developments with the Little Sun Project, and other upcoming collaborations?

Distributing solar-powered lamps and phone chargers to students and teachers as part of the Solar Schools program, with the Little Sun Foundation

I started the Little Sun Project together with solar engineer Frederik Ottesen as a social business – we sell solar lamps that I designed at a higher price in areas of the world with electricity, so the products can be sold in off-grid areas at much lower, locally affordable prices. In 2018, we launched the Little Sun Foundation as a not-for-profit organisation, so we could use donations to bring the lamps to the most vulnerable communities around the world, to people who are off the grid and beyond the reach of usual distribution models – remote schools, refugee camps and people affected by natural disasters.

“It makes solar energy tangible, putting the power of the sun in your hands”

Recently, we have been working with Ikea on a new range of solar products, called Sammanlänkad, including a charging dock, a solar panel that can be hung on a window, and different structures to suspend the light from the ceiling or place it on a table. I’m incredibly excited about the potential for this collaboration to expand our reach and raise awareness for the need to improve energy access for all, and at the same time make renewable energy solutions available worldwide. 'For me, one of the most valuable aspects of Little Sun is its role as a symbol for energy access and sustainability – it makes solar energy tangible, putting the power of the sun in your hands.

Studio Olafur Eliasson are launching ‘Earth Perspectives’ on April 22, a new artwork for Earth Day 2020 as part of the Serpentine Galleries’ ‘Back to Earth’ project

olafureliasson.ne / littlesunfoundation.org

This feature is extracted from the latest issue of Good Trouble, available now with FREE shipping worldwide. All proceeds to Extinction Rebellion. Click HERE

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.