Velvet Fist: Ellen Lesperance

Ellen Lesperance's current solo show, Velvet Fist, celebrates the work of The Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp, the much-forgotten predecessor of Extinction Rebellion. We talked to Ellen about the radical act of knitting and why the Peace Camps virtually disappeared from history.

Words by Mollie Wodenshek

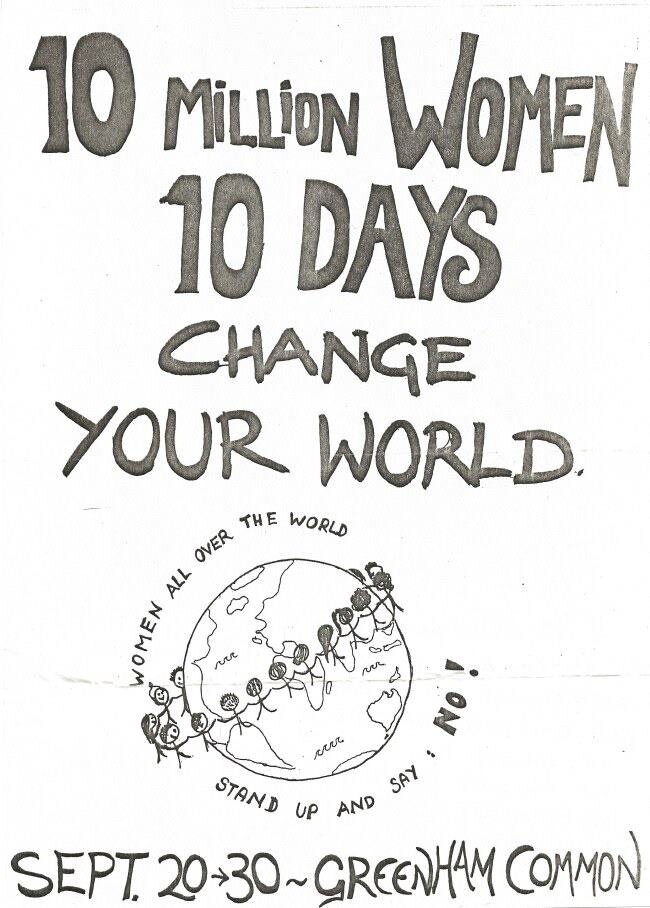

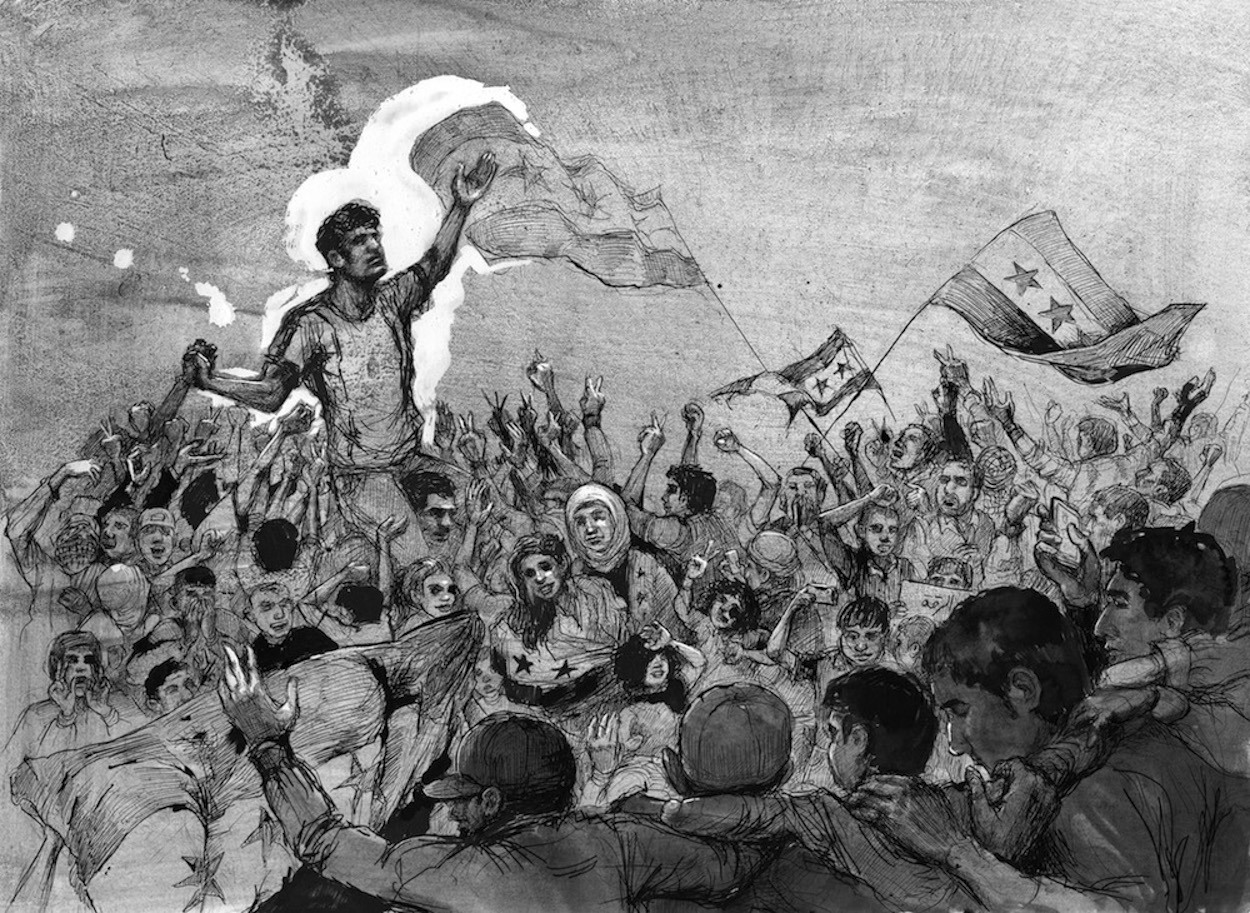

In 1981, a group of 36 women chained themselves to the fence surrounding U.S. Air Force’s nuclear weapons storage at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire, England. This act of resistance instigated a sustained non-violent protest series known as the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camps.

Ellen Lesperance, a painter born in Minneapolis and raised in the Pacific Northwest, was ten years old at the outset of the Peace Camps. Inspired by their resilience, she has spent over ten years (so far) working to illuminate life at the camps, and in turn, continue the legacy. Ellen spotlights the sweaters stitched and worn by the peace campers. The knits she uncovers become paintings of knitting patterns; an act of reorientation as the viewer is confronted with knitwear as art and thus the peace campers as radical artists. Her art is beyond practice; it is an intensive work project involving in-depth research to dig up the trailblazing work of the Peace Camps.

The peace camp protests started in ‘81, and you were just 10 years old at the time – what led you to draw inspiration from those protests?

The Greenham Common Campers recognized creativity as an anti-stance to violence – anti-war-making. They put on performances and made in-situ sculptures and a lot of it was fabric based. They were repurposing sheets; they were also knitting…I have a deep history in knitting; I used to work for Vogue Knitting in New York City in the late 90s. I started researching everything having to do with Greenham Common. I started to identify with [Greenham Common Campers’] Creative Direct Action. I developed a keen eye for their knits and started recognizing the symbolism they were using; that started a decade long obsession trying to find as many examples of their knit work as possible.

Your work is a deconstructed garment in a sense. There is the mediation of knit through paint and the historical moment that you work builds from. How does the layering in your work reflect the Women's Rights Movement at large?

The paintings that I do are knitting patterns. The majority of people look at them and don't even know what it is. Then, there's a pocket of the audience – women of a certain age – that know exactly what I'm doing because it's a vocabulary that is standard to a certain subset of the population. I'm really interested in the way that those viewers are prioritized because they see it. It's a re-prioritization of the audience.

It is also a figurative painting that's outside of a Western Male figurative art tradition. It represents garments from Greenham Common Campers and is embedded in a rich symbolic use very specific to Women's Rights history and the burgeoning queer movements in the late seventies and eighties. Also [there is] anti-nuke symbolism mixed in...

Daily Mirror cover page, 1982.

“The police would have to wade through webby lace structures to reach the women. The police had to interact with their layer of creativity.”

About Creative Direct Action – how do you feel creativity enhances action, or itself can be a form of protest?

The Greenham Common Campers would weave these webs out of yarn on the fences [of the military encampment] where they broke through so as to have people pay attention to the holes in the fence. They wove them on top of each other during the protest. The police would have to wade through webby lace structures to reach the women. The police had to interact with their layer of creativity…[The Greenham Campers] always painted and made designs on the structures they lived in. When the police came in and evicted the women, [the police] were destroying – burning down – all of that symbology. It was double and triple and quadruple violence. And the Greenham Campers made the police participate in that.

This history is not relegated as “important”. The sweaters in particular, since they don't have a framing within conventional notions of art-making, are doubly negated.

I was particularly drawn to one painting from the show with the rainbow and the upside-down pink triangle, which is very familiar to the LGBTQ+ community. How is this moment of resistance also intersectional?

One of the primary symbols that the campers used was the rainbow. The rainbow is so ubiquitous today as a pride symbol and there is so much merchandise that features it now, but it can't be overstated how risky it was in the early eighties to be queer in public and to display an emblem that identifies you as queer in public.

A lot of the negative press for the Greenham Campers wasn't primarily because they were anti-nuke activists, it was because they didn't conform to standard feminine ideals. They were called every slur imaginable in the press – mocked for being queer; mocked for shaving their heads. There were lots of violent acts enacted upon them, and it was really brave.

Did you knit the sweater yourself that is going to be lent out for Congratulations and Celebrations?

Yes! I did, yes!

How do you feel that has added to the Greenham Commons Women Peace Camps and the Velvet Fist exhibition?

This is the sweater’s fifth year! It is a single sweater that gets circulated to anybody who has DM’d (direct messaged) me on Instagram. I send it to anyone who is interested in wearing it to perform a completely self-defined act of courage. They share a picture and it gets posted and their story gets posted.

When I started this project, I would knit a lot of the paintings that I made, and those garments were sold with the paintings and just sitting in people's collections. They didn't have a function; they were exhibited or held where ever people keep their collections. My primary interest was to bring the sweaters back into the culture and Congratulations and Celebrations was my way of figuring out how to make them function.

Ellen Lesperance. Congratulations and Celebrations Sweater. 2015-ongoing. Courtesy of the Artist.

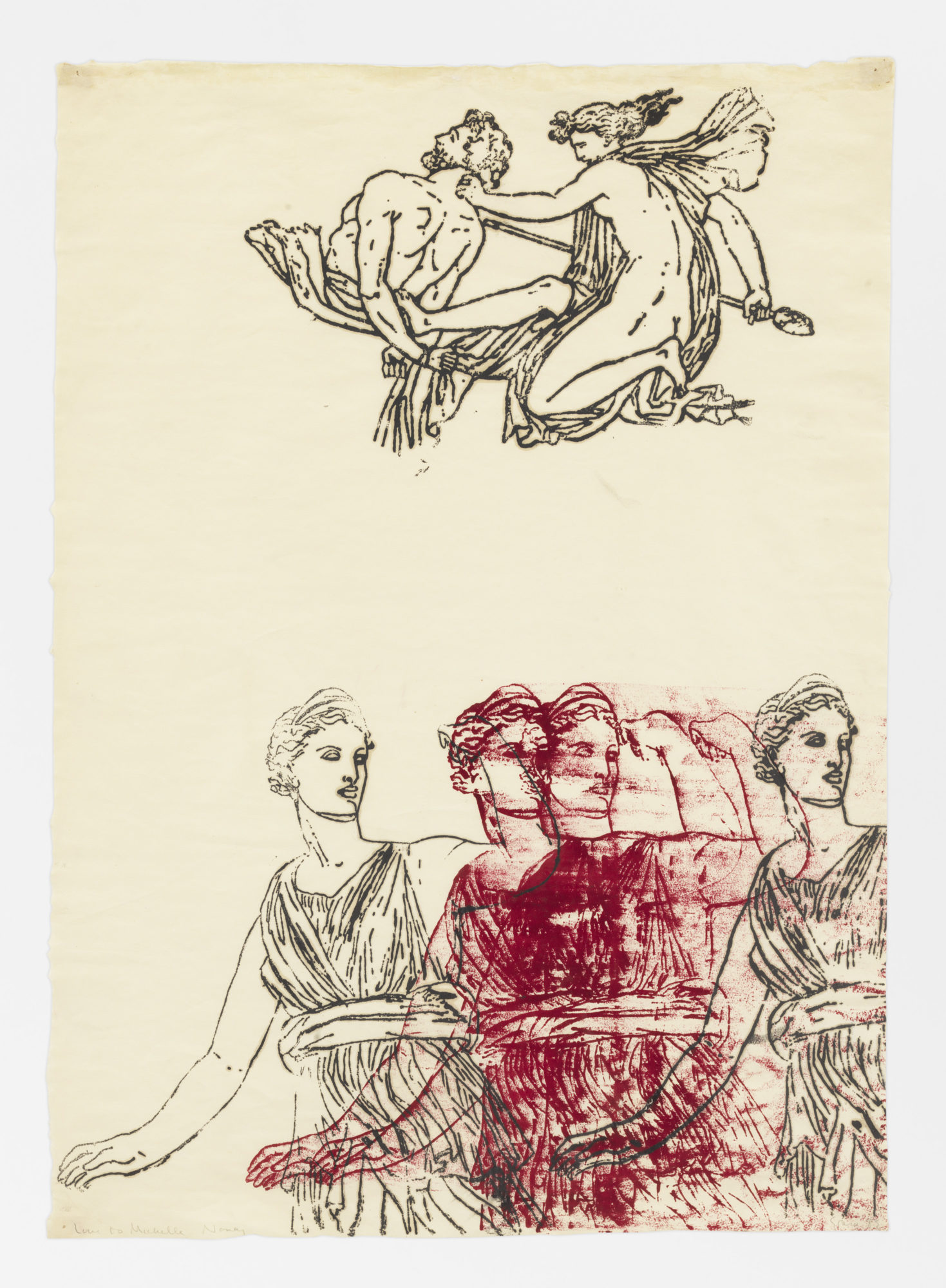

Ellen Lesperance. As If The Earth Itself Was Ours By New Covenant. 2018. The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchase with exchange funds from the Pearlstone Family Fund and partial gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., BMA 2019.155. © Ellen Lesperance

Ellen Lesperance. I Looked Towards Her, She Looked Towards Me, We Both Could See the Common Free. 2018. Courtesy of Jorge M. Pérez Collection, Miami. © Ellen Lesperance

With Congratulations and Celebrations, borrowers enact a self-defined act of courage – what kind of things have come out of that?

Oh my god, it can be as banal as somebody who was afraid of heights wearing [the sweater] on a Ferris Wheel – which is so sweet and cute! Someone wore it to the first Women's March in Washington, D.C. Somebody wore it for their first dose of gender-affirming hormones. People have worn it to have difficult conversations. Some have worn it when their dog died. It's all over the map; It’s just everywhere.

How will you continue to illuminate women in history and art after this project?

I'm still working on the Greenham Commons series. I have a stack of Greenham Commons sweaters that I need to translate into patterns so that work is continuing. The project extends out to other activists that are wearing argumentative knitwear and to certain other subsets of people. I'm really interested in the way that fashion was potentially used by other figurative painters in the feminist art revolution, somebody like Sylvia Sleigh; but I'm also interested in the history of knitting and the representation of female bodies in fashion knitting. I feel like there is a lot of work to do. I'm not afraid that I won't have anything to make!

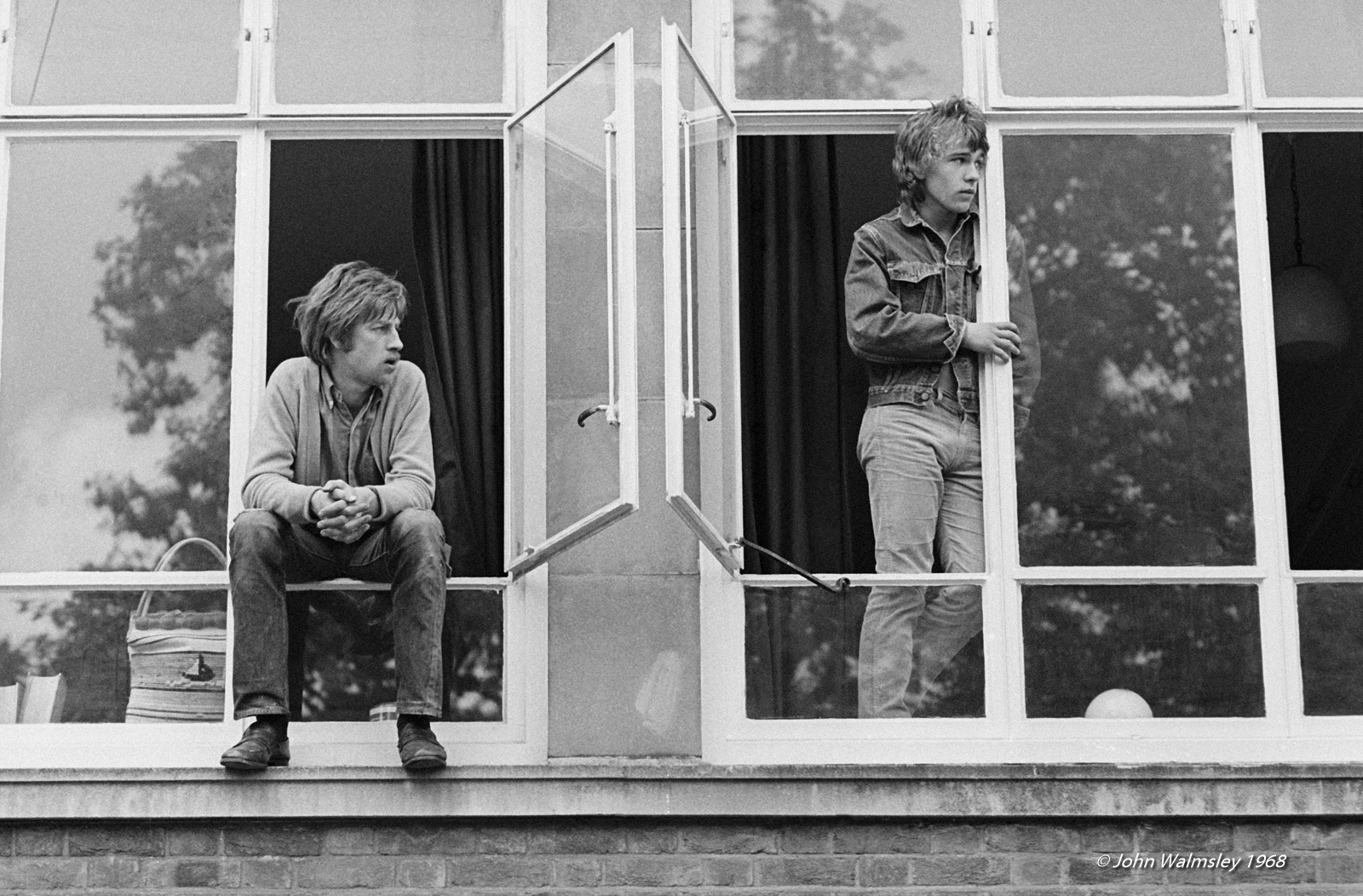

Date unknown. ©The Danish Peace Academy

“Velvet Fist” is on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art from January 26 until June 28, 2020, and features seven works from Lesperance’s ongoing “Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp” series, as well as a new artist book of archival sources. Also featured is Lesperance’s participatory project, “Congratulations and Celebrations”, through which members of the public can borrow a hand-knit sweater to perform a personal act of courage.

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.