Nasty Talk: Feminist Art in the Age of Trump

"Such a nasty woman." – third and final presidential debate, October 2016. In an essay written for the show Nasty at the Daniel Faria Gallery, Rosemary Heather looks at the role of feminist art in the age of Trump, and why the word 'nasty' has become a new emblem of resistance.

Donald Trump deriding his electoral opponent Hillary Clinton, as a “nasty woman” is hardly the biggest problem associated with the new American president. The insult delivered during the third presidential debate does, however, have relevance to the bizarre state of affairs that is the United States in 2017. The country is currently in the grip of a self-inflicted catastrophe. Chaos is not too strong a word for what is unfolding; who knows where its all heading? But just think what the cause is — the threat of a woman holding the country’s highest office. Reality TV host and fraud businessman Donald Trump was thought a better alternative than that.

Elizabeth Zvonar, Join The Resistance

Nasty personifies the idea of an embodied threat. On the occasion of Trump’s inauguration, the word takes on an added significance: as an emblem of resistance. Taking this challenge on, Nasty the exhibition is organized to coincide with the inauguration and the worldwide protests that are accompanying it. The idea of nasty connects with art in the latter’s embodied seductions — art is always in some sectors considered dangerous, in a tangible but hard-to-define way. We know from Plato that art is thought to be a program for deception; like misogyny, the social prejudice against it runs eons deep. If artworks and women still engender a suspect reputation, what is the problem exactly?

Aleesa Cohene, Like, Like

Going back to Hillary, the New York Times ran an illuminating opinion piece last November 5th, three days before the election. Titled, “The Men Feminists Left Behind,” the author Jill Filipovic talks about an America (and by extension all of the West) in which men have enjoyed a default dominance, forever. “It was mostly white men in charge and it was white male experiences against which all others found themselves contrasted and defined.” The clearest indication that this status quo might be undergoing change is — what else? — the resistance to it expressed by Donald Trump’s electoral success. Filipovic outlines the many advances women have made in the past decades — “For women, feminism is both remarkably successful and a work in progress” — and notes that “men haven’t gained nearly as much flexibility.” Accurately derided in Vanity Fair as “shallow and mediocre,” Trump as U.S. President is living proof that men still rule, regardless of how ill-suited they may be for the job.

Installation view

Is the argument of this show then that artworks are like women? Clearly, yes. More specifically it proposes that both derive their power from a position of in-equality. This position, however, produces in its turn an entire world of invention. Writing about Clinton’s loss to Trump in the election, the philosopher Rebecca Solnit notes: “power… is a male prerogative, which is to say that the set-up was not intended to include women.” If power is not “set up” for women to share in, they have to figure out other ways to get it. Faced with this reality, the appurtenances, so called, of the feminine are a way of owning it — if not power necessarily, then an equivalent force all its own.

Jennifer Murphy, Mirror

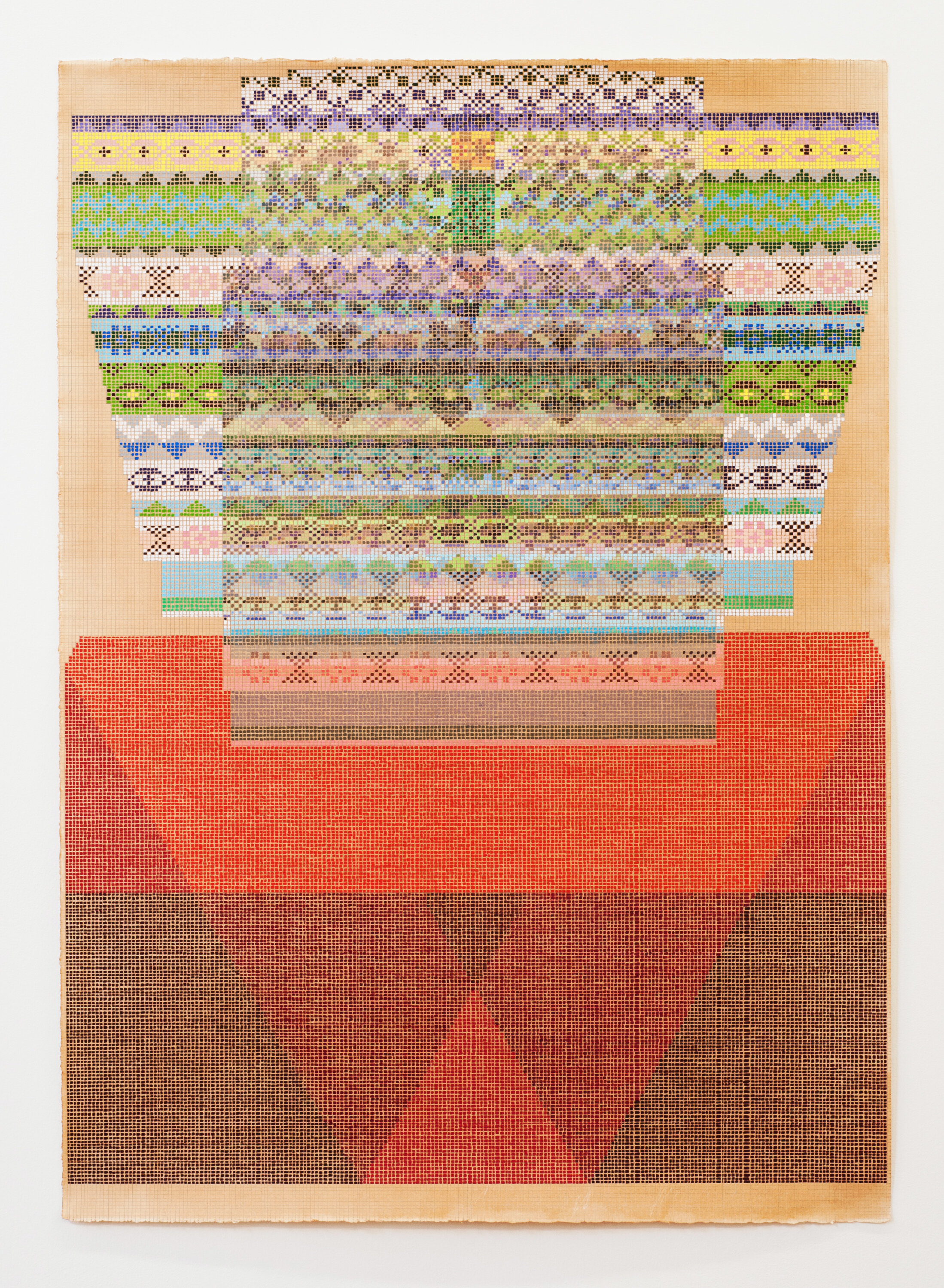

Although the works in the show are not overtly political, a heightened relevance for feminist politics provides the context for this exhibition. Nasty presents work by eight women artists, each one in some way investigating the visual culture of femininity. The types of practices on view are wide-ranging. Through surface collisions of ornamentation and draping, Shannon Bool evokes the figure of the feminine, as both historically specific and timeless. Stiletto heels, rendered as both support and staging ground, form the basis for Elizabeth Zvonar’s evocative collages. The power dynamics of looking take on new — gendered — meaning in Nadia Belerique’s shelf sculptures. Jennifer Murphy’s delicate sculptural collage works hint at the poisoned barbs that lie beneath the natural world’s seductions. Against an astringent blue background, the title Shady Lady (2010), suggests the gendered nature of Kristine Moran’s gestural abstractions. Aleesa Cohene’s 2009 video installation Like, Like discovers ulterior narratives for mass culture’s female icons. With Valerie Blass’s 2009 work Touche du bois, wood and jeggings are combined to be somehow confrontational. And finally, and hardly least, Kara Hamilton contributes further embodied aggressions with the beast-like Tonka, a work she made in 2015.

-Rosemary Heather, 2017

Top image: Elizabeth Zvonar, Origin of the World

Nasty is at the Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto, CA until March 4

ACTIONS

On March 8, The International Women’s Strike is calling for a day of action, planned and organised by women in more than 30 countries. Find out more HERE

Every 10 days, Women's March takes an action on a different issue – www.womensmarch.com

Valérie Blass, Touche du bois

Author account for the Good Trouble hive-mind.